Syke!

In 1916, at the height of WWI, two diplomats met in secret to outline the future partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. Those diplomats, the United Kingdom’s Mark Sykes and France’s François Georges-Picot, approached this undertaking with all due gravity and diligence.

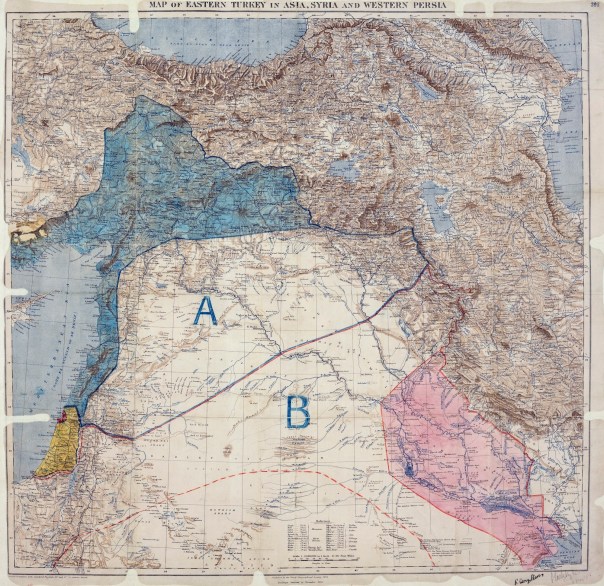

Jokes! Nah, they more or less scribbled on a map with crayons, dividing the region between the U.K., France, Russia, and Italy. Their proposed boundaries split local polities — in some cases, they seem to have used the letters on their map as landmarks — and showed no intention of honoring their agreements with their Arab allies. Shrouded in secrecy, the agreement only came to light when post-revolution Bolsheviks published the whole thing, proving to the world that the Triple Entente had returned to their bad habit of cutting backroom deals.

This ignominious treaty is the topic of Sykes-Picot, the trick-taking, dry-erase, area control game by Brooks Barber and Hollandspiele. This one is angry, polemical, slapdash, and wholly on-point.

To get to the bottom of Sykes-Picot, we need to proceed through a few different layers, digging through humus and soil and gravel, before at last striking bedrock. Along the way, each layer reveals a very different sort of game, one that redefines what we witnessed earlier in our excavation.

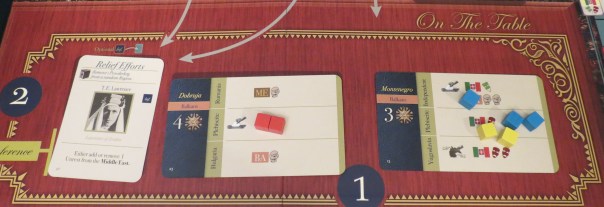

The topmost layer, naturally, is “the game itself,” the plaything on the table that players encounter when they arrange its components before them, shuffle the cards, and set to the task of figuring out how to play.

Sykes-Picot is indeed a trick-taking game as well as an area control game. For the most part, Barber proceeds as straightforwardly as such a hybrid permits. The deck consists of five suits, two for the United Kingdom and two for France, with the fifth representing international control. Winning a trick means you must pen something onto the map, the shape and color of which depends on the cards that were played. This quickly results in a certain degree of friction. It’s nearly always better (but not always!) to win a trick, giving you the option of which of those two cards to mark onto the map.

That map is presented as a hex grid, faintly (perhaps too faintly) watermarked with the actual map that Sykes and Picot doodled over. Your objective, broadly speaking, is to secure certain strategic objectives for your colonial empire. There are shipping centers, strategic military zones, and cultural heritage sites, any of which might be a priority depending on which of your agenda cards — separate from the actual trick-taking cards — you have drawn. Think of these as the directives handed down by your government.

As noted earlier, there are three colors that can be penned onto the map, red for the U.K., blue for France, and black for international control. Each trick follows the same format. The winner takes either of the cards played into the trick and marks its boundaries onto the map. This isn’t as simple as a binary France-or-U.K. division. Instead, both sides can either mark influence (an outlined hex) or outright control (a filled-in hex). Crucially, to stave off any future conflict between superpowers, these sides’ controlled territories may never border one another. Influence? Sure. But outright control is a no-no.

This is only the first of a few complicating factors.

The black spaces that indicate international control, for example. At first, they seem benign enough. Before long, however, it becomes apparent that these are one of the best routes for denying your opposition access to their strategic objectives. If your rival-ally seems determined to access various cultural sites, why not assign Jerusalem to international oversight? Like the rest of the game’s marks, these can only be placed adjacent to anything you’ve already penned onto the map, so you can’t teleport into any old corner. But this gives every mark a little more weight than it had before. Creep too near to a desirable zone, and it’s entirely possible that your opponent will hand it over to Russia before you can seal the deal.

Meanwhile, losing a trick affords its own benefits. The loser has the option of penning the remaining card onto the map. Depending on how the trick went down, that might be as good as winning. But losing permits other options as well, such as swapping a card with the set-aside triumph card, switching the ultimate suit for the rest of the hand.

Or, perhaps, transforming some of their influenced hexes into control. Depending on how the game has proceeded to this point, this can turn a lost trick into an unlikely victory, seizing the sites of your government’s secret agenda and locking your ally out of marking their own control.

What this achieves, then, is an emphasis on tempo that will prove familiar to weathered trick-takers. Sometimes you want to win a trick, sometimes you want to yield, but always you hope to advance your overall position. Like Cole Wehrle’s use of the genre in Arcs or Peer Sylvester’s in Brian Boru, trick-taking becomes a backdrop to a dialogue between players. Barber approaches trick-taking more directly than those designers, with fewer frills or departures from the formula, but the effect is similar. Through the language of play, you are conversing. Each card becomes a thrust or parry in a larger dispute.

If we focus our lens purely on gameplay, there are some hitches to Sykes-Picot.

The map, for one. Everything is so close together that there’s rarely any breathing room. I mentioned earlier that getting too close to an objective can prompt your rival to block your attempt to secure it by instead assigning it to international control. That’s true. But the map is so compact, with so few hexes in between points of interest, that it’s usually a fairly trivial thing to steal control in this manner. As soon as a player tips their hand that they regard a particular type of hex as desirable, they’ve effectively pasted a bullseye on their backside.

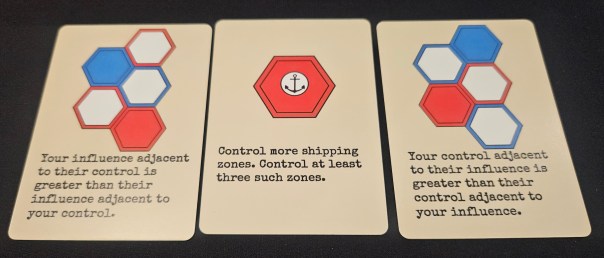

Or there are the agendas themselves. Both sides have six agendas, and they’re perfect mirrors of one another. Depending on the draw, both France and the U.K. might hope to secure shipping, military, or cultural zones. Another agenda sees players contesting the central portion of the map — although in an unexpected wrinkle, you want to either influence the center or have your opponent control it, usually prompting an early-game scramble to mix your control and influence over those three hexes. The remaining agendas offer contrasting objectives to have more influence next to your opponent’s control or vice versa. There’s some wiggle room in there, but not so much that it stops feeling claustrophobic. Once you know the range of possible objectives, your rival’s choices are largely transparent.

When evaluating Sykes-Picot as a trick-taker and area control game, it’s hard not to note these as flaws. In terms of play-pleasure, both prove severely limiting. It’s possible to swap out one agenda per round, but there’s a punitive element to consider, forcing you to yield some of your territory to international control. (This can be useful, it should be noted, especially if you’ve already established that your rival hopes to control or influence a certain number of zones adjacent to your own.) The whole thing is frustrating.

Except it turns out these limitations are what bring us closer to the game’s bedrock.

To be clear, these critiques are valid. As a plaything, Sykes-Picot has some stark issues. It’s often galling. The appearance of a particular card at an inopportune time, the composition of the agenda and diplomacy deck, the willingness of your opponent to cut deals — these can all inform the experience, whether to shore it up or curdle it into a more rancid concoction.

But it’s meant to be rancid. Your agendas, so secretive and hidden, are meant to be transparent. The map, with its limited kilometers to squabble over, is meant to be suffocating.

This launches a larger investigation into history and statecraft as gamesmanship. The obvious thing about Sykes-Picot is that it evokes the same physical actions that Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot undertook in 1916. Look, you’re scribbling on a map! Just like they did! The actual polities and peoples you’re drawing over don’t matter to your imperial objectives! It’s a commentary!

But I suspect Barber is striving for something more wide-ranging than a shared medium. Using pens on a dry-erase map is the equivalent of pointing foam pistols at each other in Ca$h ‘n Guns. Here, the connection between players and their subjects is subtler but more all-encompassing. Like Sykes and Picot, the players of Sykes-Picot are constrained by geography. There are only so many ports, so many bottlenecks, so many holy sites. Similarly, they’re constrained by the limited scope of objectives passed down by their prime ministers and presidents.

More than those, though, they’re constrained by the assumptions and attitudes brought to the table by imperial negotiators. The blitheness demonstrated by Sykes and Picot in divvying up post-Ottoman territories becomes the players’ blitheness. The medium being replicated isn’t the pen, or isn’t only that. It’s the play.

Because Sykes and Picot were playing a game as well. A game of empires, often cast in explicit gaming terms, tallied by marks on a map and the feeling that they were getting one over on their partner. Like two friends seated at the table temporarily becoming enemies, but only within the theoretical realm of play, Sykes and Picot were also friend-enemies, ally-rivals, gentlemen cutting gentlemen’s agreements about the shape of the post-war world. Recall that the First World War was in full swing! The Ottoman Empire had just smashed the Entente at Gallipoli! The Battle of Verdun was killing hundreds of thousands of their countrymen while they painted over a map! And these men carved up one empire to serve the interests of their own empires, all while thumbing their noses at both their global and partisan allies.

If Sykes-Picot offers a commentary on the insouciance of statesmen who approached history as a game to be played, then it also offers a second underlying commentary on the insouciance of games that seek to evoke history by sticking to just the facts, ma’am.

It’s easy to imagine an alternate version of Sykes-Picot that leaned into the granularity expressed by traditional conflict sims, full of intersecting allegiances, conflicting national agendas, and the many geographical treasures of the Ottoman Empire. Such a game would likely feature multiple players, like some shadow version of Geoff Engelstein and Mark Herman’s excellent Versailles 1919. Before the Bolshevik Revolution tore up any outstanding Romanov agreements, Russia was set to receive Constantinople; Italy did in fact claim the southern portion of Anatolia.

But this degree of granularity would prove misleading in its own right. It would give the impression that Sykes and Picot were acting in good faith. That their squabbles were meant to draw careful boundaries rather than gobble up as much territory as possible.

Sykes-Picot, as a trick-taker and area control game, played with red and blue markers on a laminated map, presents a simplified version of the Sykes-Picot Agreement. It isn’t concerned with strictly representational history. Like, obviously.

In its simplicity, however, Barber’s rendition speaks to a different perception of reality, one we might label impressionistic rather than detail-oriented. One of the Sykes-Picot Agreement’s defining characteristics, to some the defining characteristic, is its lack of attention to issues on the ground, cutting through ethnic and sectarian lines with hardly a care for their long-term ramifications. This is the Sykes-Picot Agreement that has lodged itself in the memory, that Bolsheviks published to humiliate England and France, that ISIL jihadists still pledge to overturn today. In that regard, this presentation of the agreement is more accurate than our theoretical conflict sim could hope to be, eschewing the details that Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot might have nitpicked over, but which ultimately mattered very little to the actual drafting of their deal.

Given the recent direction of Hollandspiele, this makes sense. The publisher, Amabel Holland, has compared her press to that of a zine, interested in crafting games that are opinionated and rough around the edges, but illuminating in their own right. This approach flies in the face of modern design and publication assumptions, which prioritize polish over immediacy. But there’s a lot to be said for immediacy. I’m reminded of John Darnielle’s early approach to music, where he often composed, performed, and recorded a piece all within a few hours, the clickety-clack of the tape deck audible in the final track, because any further polish would not only fail to improve the music, but brush away its rawness of feeling and expression.

In that regard, Sykes-Picot presents the inverse of a traditional conflict sim. It speaks to the way the Sykes-Picot Agreement has been received in living memory, not as a function of data tables and careful statecraft, but as an act of faraway disregard and imperial violence.

One final detail cements these layers into a single coherent stratum. As in Amabel Holland’s Endurance or Xoe Allred’s Persuasion, Barber plays coy with his victory conditions. Both players can theoretically achieve three agendas over the course of the session. Should one player complete more agendas than their opponent, they’re declared the better diplomat.

But Barber clutters what might have otherwise been a straightforward victory state. First of all, there are no winners on the national scale; this is a personal conflict between Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. Historically, the former grew to suspect that the latter had performed better in their negotiations, which ate at him in the later stages of his life. This again speaks to the gamesmanlike nature of the whole endeavor, more about individual personalities than national interests.

Barber establishes two further concluding states. If both sides meet the same number of agendas, they’re declared an even match. If neither meets any agendas, then, in Barber’s words, “They both need to reconsider their careers and go home in shame.” The stakes are international, but success or failure is personal.

This open-ended nature informs the rest of the design: the small number of agendas, the too-close geography, the tricks with their variable benefits for winning and losing, the commentary both on history-as-games and games-as-history. Because there’s nothing preventing players from competing as usual, laboring to block every avenue for rival success, or even working together to craft an equal outcome for both parties. While the exact details on the diplomacy cards are verboten, agendas can be discussed, shared, or lied about. In this way, players are invited to set their own parameters for the partition of the Ottoman Empire, disclosing their objectives or keeping them close to the vest, working in tandem or opposition. Or perhaps both at the same time, with one player emerging as the shrewder diplomat by feigning concessions or closing an unexpected agenda.

It’s always a treat to find a game that keeps unfurling new dimensions. Sykes-Picot is one such game. As a trick-taker and area control game, its initial stages are rough and fumbling.

But touring its various layers of meaning and interactivity reveals an unusually clever plaything, one that plunges its players into the testy, self-obsessed, and blithe mindset of its drafters. With zine-like sensibilities and a defiant stance, it expresses hard opinions that veer away from the accepted tabletop methods for portraying things like treaties and diplomacy, but nonetheless speaks dingier truths about how imperial power is crafted and maintained. Ego. Carelessness. Men who have decided they know better than everyone else. This is what those lines on a map mean. And Sykes-Picot refuses to pretend otherwise.

A complimentary copy of Sykes-Picot was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read the first part in my series on fun, games, art, and play!)

Posted on June 16, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Hollandspiele, Sykes-Picot. Bookmark the permalink. 3 Comments.

Fantastic review, thanks. Not something I am likely to play any time soon, but I enjoyed this enormously. And learned something new about John D’s existence!

Thanks for reading!

Pingback: SDHist 2025: Day of Copium | SPACE-BIFF!