It’s Pronounced Ver-sah-ay-LEES

Not to go all historian on anybody, but I’m going to say something that may prove contentious: matters of history are only settled when they stop mattering, whether through consensus or lack of interest. The corollary, of course, is that very little about history is ever settled. This is magnified when the topic occurred recently enough that people can trace a line from former circumstances to ongoing considerations. It isn’t hard to find examples. How often have you heard it said that slavery was sure terrible, but also a necessary evil? Or that Christopher Columbus shouldn’t be judged by present-day standards? Never mind that both statements can be torn to shreds. They aren’t said because they’re factual. They’re said because they point toward a moral framework that’s mutable. If yesterday’s suffering can be dismissed as necessary or chalked up to changing values, then today’s suffering can be similarly dismissed. It’s history as comfort food, carefully mashed so that no teeth are chipped and no stomachs are unsettled in the process of digestion.

The 1919 Treaty of Versailles no longer lingers in the historical vernacular, but experts in the field continue to debate its implications. We occupy a world shaped by its outcome, from modern political boundaries to the concept of a global governing body. Later conflicts, including the Second World War, may have been directly spurred by its approach to war reparations, and while the independence movements of the 20th century came of age after WWII, Versailles is where they were brought kicking and hollering into the world.

Which means that Mark Herman has now designed two games about shaping the past century through treaty-drafting. The first, Churchill, represents more recent agreements. But in its own way, Versailles 1919, which Herman co-designed with Geoff Engelstein, seems like the more relevant of the pair.

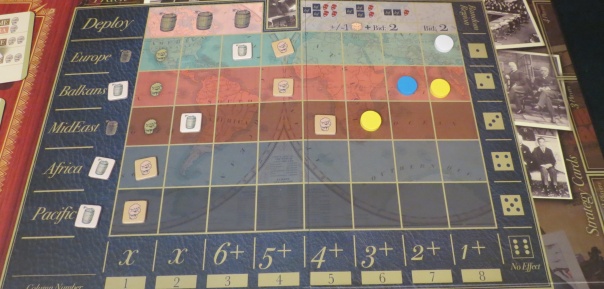

To capture what Versailles 1919 is about, the best starting place is the image of a young cook’s assistant, or perhaps a chef, or maybe a lowly dishwasher. This may prove startling to some. It would seem more appropriate, perhaps, that a game about divvying up the world between victors should have as its central image the world itself, oceans and continents reporting dutifully to meet their new managers. But games with maps have a tendency to become about their maps. Versailles 1919 represents the world as a spreadsheet rather than as geography. Without the benefit of its contours, loaded with assumptions and prejudices and clusters of countries whose names are less familiar than others, the focus becomes, well, personal.

Personal enough for a young kitchen worker. Perhaps the uncertainty of his current occupation is also startling. Which is he, cook’s assistant or chef or dishwasher? That, unfortunately, is simply a fact of how history operates more often than not. Details rounded out, memories grown fuzzy, facts supplanted by recollection. Regardless, the young man is kitchen staff, not a statesman like Woodrow Wilson, David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, and Georges Clemenceau, the Big Four who now squabble over the coming shape of the world. The young man is still assessing what he thinks of the world’s shape, whether it is a globe or a spreadsheet or some other form that will arrange its crisscross of allegiances and suzerains into their proper columns.

This isn’t to say he doesn’t have opinions. He has strong opinions, and he doesn’t hesitate to voice them. His arrival here, at the six-month drafting of a complex treaty, is a witness to the ferocity of his views. Along with other compatriots in Paris, he has helped author a request of those statesmen. You see, he is not from Paris, is not even from Europe. He is Vietnamese, subaltern, a colonial subject of France, and when he heard President Woodrow Wilson of the United States speak of self-determination and the impartial adjustment of colonial claims, he yearned for a guarantee of civil rights for his people. Not even independence. Mere recognition of his status as a human being, someone capable of weighing in on the course his country will take going forward.

The request he has helped author will go entirely ignored.

There are simple histories and there are complex histories. Often they are the same. It would be easy to label that moment as the one when a villain or a hero was born. The young man spurned, the revolutionary turned out. But there are decades to go yet. That young man’s appreciation for Wilson’s vision will first blossom into affection, forged when American troops aid the Vietnamese in throwing off the yoke of the Imperial Japanese. Later he will be so certain of an alliance with the great United States that their rejection will sting like a slap to the face. War it will be. A long, bitter war. He will die long before it’s finished. By that time, he will have lived longer as Ho Chi Minh than as Nguyen Ai Quoc. Easy to misremember which chores he performed in the hotel kitchen where diplomats discussed the shape of the world.

Here’s something else Versailles 1919 is about: icons. Not as many as you might expect, but enough that someone may well forget the difference between punishing Germany economically or with soldiery stationed along their borders. Such distinctions aren’t always important. As with many games, it’s all too easy to forget the meaning behind the icons, to only see the icons as points rather than as implications.

Herman and Engelstein have solutions for this remoteness, or at least mitigations, but none are quite as important as their willingness to put a human face alongside each pair of issue cards. The issues themselves are relevant of their own accord. Pulling one from the deck at random functions as a miniature lesson in unintended consequences. Here is the Kiel Canal. Should it be destroyed or forced open for trade? Here is what remains of the broken Ottoman Empire. Should France or the UK should be given the mandate to partition it? Here is Vietnam. Should that young dishwasher’s plea be heard or ignored? These are global occurrences. Their consequences will be far-reaching. Wars will be fought over them. Other young men will be buried in the soil of the nations that are born or strangled in this moment. Either way, these big issues, these global affairs, are brought back into focus because they’re about people. Maybe even a person right there next to the issue being debated, a diplomat or a Zionist or Rupert Murdoch’s dad or a dishwasher.

I’ve been accused of reading too deeply into the games I play. Fair enough. I wear it like a badge of honor. Where some see only cubes placed atop spaces, I believe it’s valuable to understand what those pieces and spaces are meant to represent. A US influence counter in Twilight Struggle’s Laos/Cambodia space isn’t just a digit in the vicinity of Burma. It’s Operations Menu and Freedom Deal. It’s thousands of bombed civilians. It’s the delaying of the Khmer Rouge’s conquest. It’s armed Hmong tribesmen. When the war flounders, many of them will begin resettling in Minneapolis.

But I’d also be the first to say that not every game supports this process of looking past the pieces. Chess may be enlightening about the class assumptions of those who designed and played it — pawns and peasants are expendable — but I wouldn’t want to fight under a general who learned all he knows about warfare from castling and en passant. Similarly, just because a game is about drafting a treaty doesn’t mean it will reflect the realities that influenced and stemmed from that treaty’s negotiations. All that stuff I noted about how Ho Chi Minh was a petitioner at Versailles and went on to become one of history’s most famous revolutionaries isn’t the sort of thing that will make it into every game based on history.

It’s true that Versailles 1919 doesn’t function as a personal history of Ho Chi Minh, just as it doesn’t reveal the full biographies of Winston Churchill, Millicent Fawcett, T.E. Lawrence, or anyone else who attended the negotiations. Such details are incumbent upon the player to learn in their own free time. Instead, Herman and Engelstein provide a framework that demonstrates the pressures its statesmen were feeling as they molded the modern world.

One significant example demonstrates both the setting’s before and after. When an issue is claimed, its new owner must decide how it will be resolved. Often these decisions have significant ramifications. Icons are worth points depending on which side you’re playing, but that’s only one layer. It’s also possible to upset entire nations or regions. The issue of Korea, for example, can resolve in one of two ways. Either you can award it to Japan, which will make the Japanese happy but anger the rest of the Pacific, or you can grant it independence. Prepare for the Japanese to feel rather snubbed about that.

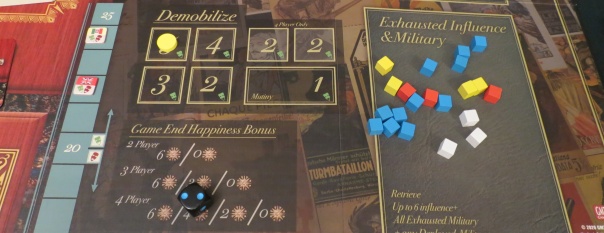

In other words, there isn’t an obvious outcome. The first option may cause the Pacific to spiral toward war. You could deploy troops to the Pacific to make uprisings there less likely, or at least let you settle the outcome more easily if a conflict does break out. But deployment isn’t an easy call. Remember how you recently fought a world war? Remember all those mothers pining for their boys to come home? Keeping the peace may seem prudent, especially if you have a vested interest in a region. But it also tends to make everyone grumpy that you’re getting into yet another ruckus. Maybe it would be better to demobilize an army or two. It will become harder to project your authority across the globe, but at least you won’t have a mutiny on your hands.

Happiness matters, and not only your own nation’s happiness. In the option of an independent Korea, Japan becomes upset. Who cares? Well, you do. Or you might, depending on your long-term strategy. Strategy card, that is. Every game features only a few, visible to all. Whenever the first uprising occurs, everybody picks one that they will score at the end of the game. Now all those icons are worth tangible points.

There are three ways to look at this. The first is entirely ludic, in that strategy cards provide necessary direction to your negotiations. Not only do you want certain things, but other things may be yielded more readily. In other words, the interests of the Big Four may collide, but there are also possibilities for collaboration. An isolationist strategy demands icons for industry, self-determination, and happiness, while also trying to bully Italy and Japan out of signing the treaty. Meanwhile, a strong stance against Communism requires stout empires and fleets, anti-communism icons, and needs everybody to sign the treaty if possible. The intersection of these two objectives generates pressure points, outright disagreements, and shared goals alike. The owners of these strategies would have very different opinions about the happiness of Japan while cozying up like twins in a crib on other issues.

Of course, it’s also possible to regard this system as starkly ahistorical. When Clemenceau heard Wilson’s Fourteen Points, he famously retorted, “The good Lord only had ten!” Yet in Versailles 1919 there’s nothing stopping France from championing the conclusion of national empires. Not every strategy card is as prone to historical misalignment, but it is noteworthy that not every game will see Britain, France, the United States, and Italy pursuing the same objectives.

I couldn’t care less. One of the specters of historical game design is hindsight; namely, the realization that players can operate from what actually happened — or what didn’t. Hindsight may tell us that the battle will be won by whichever side first claims Big Round Top, or that inventing radar can turn the tide of an aerial conflict. Here Herman and Engelstein sidestep the problem by focusing once again on personality. In this case, your own.

There’s a reason the 1919 negotiations took half a year despite enormous pressure to get the paper signed. That outburst of Clemenceau’s is very much the point. He could not, after all, have sputtered in frustration had he already known that Wilson’s stance on colonial property would be at odds with his own. I’ve written in the past about something I call feedback, when a game’s elements come together to evoke a coherent feeling of place and action. Put into the terms of a historical game, to immerse its players in the same decision space that was once endured by that event’s actors. Versailles 1919 does more than ask its players to retrace the steps of Wilson, George, Orlando, and Clemenceau. It requires you to walk a mile in their boots. Or at least a few steps.

Such a tour couldn’t be realized without the possibility of somebody stealing your thunder, a friend picking a strategy at odds with your own selection, or a rival becoming an unlikely bedfellow. Negotiations in Versailles 1919 can run hot. At one level, you’re blustering about icons. At another, your frustration is more about the revelation that even in forging peace, you’re at war. A war of pens and distant shores, yes, but a war nonetheless.

More importantly, it’s a personal war. This is the accomplishment of Herman and Engelstein. Their history is evocative rather than ironclad, playable rather than simulated. But it’s also human. Whether it’s the figures who wend in and out of the halls of state, the armies missed back home, or the leaders whose visions you seek to actualize, Versailles 1919 always draws its focus back to those who forged the treaty and those who were impacted by it. As lofty as diplomats, as lowly as dishwashers. Now that’s a depiction of history I can get behind.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on October 19, 2020, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, GMT Games, Versailles 1919. Bookmark the permalink. 22 Comments.

Je parles français, et le nom Versailles se prononce en anglais “vair-SIGH”. 🙂

… foux du fafa?

Dan, this is a masterful review. Excellent approach.

Agreed, you really capture what makes this such an interesting game.

Thanks, Matt and Christian!

“It’s history as comfort food, carefully mashed so that no teeth are chipped and no stomachs are unsettled in the process of digestion.”

See, I’d say that pretending people’s values aren’t products of their time and place and that if we had lived back then we *definitely* wouldn’t have done things that were normal then is a lot closer to history as comfort food. But then, as you say, Versailles isn’t about coming to a perfect solution, it’s about trying to wrangle an imperfect one in your favor. Walking a mile in someone’s shoes, which I think is the ideal of historical games. To put you in the vices that lead to the decisions that created the world.

“Of course, it’s also possible to regard this system as starkly ahistorical.”

I haven’t had the chance to take the game out for a spin yet myself, but I got the impression that the issue card choices that correspond to each of the powers generally tilt the powers towards ones that are at least generally in character. Like, choices that give self-determination tend not to give the US unhappiness on top of that.

Oh, I broadly agree. But here’s the thing: the people in my corner of the world who rationalize slavery and figures like Christopher Columbus aren’t doing so because of some self-awareness that they too would have been complicit in the crimes of the period. They rationalize because it lets them ignore the horrors of yesteryear, and therefore ignore their place in the injustices of today. You’ll get no argument from me that values can’t change over time, or that our alignments aren’t largely informed by our environment. But the former is a stance that always strikes me as somewhat oversold. Slavery and Columbus’s slaughter aren’t only horrifying in retrospect. They found opponents even in their heyday. Those outspoken voices aren’t always the clearest or the loudest, but they’re the ones I appreciate best.

Oh man, wait until you hear how Versailles, Kentucky pronounces it

Well, “Versailles” may end in “-ay-LEES” in this title.

But to anyone who speaks French as a first language…not so much (check out Forvo.com). 😉

Hand grenade close, though. Great review; thoroughly enjoyed it, as I do all your reviews.

Thank you for your kind words! Although I must point out that I know how to pronounce Versailles. I suspect this is the flattest a joke has ever fallen on this site. =)

What title. What a review. Outstanding writing and insights, Dan.

Have you had a chance to return to Versailles 1919 since your initial impressions? If so, have multiple plays evoked the same praise and admiration?

Again, a wonderful review, Dan.

Thanks, Sam. We’ve revisited V1919 a few times, and I’m always struck by how carefully and sensitively it brings those thoughts to the fore. It really is a wonderful game.

Little late to the party but do you prefer Churchill or Versailles 1919?

Whew, that’s a harder question than you might think. (Or hey, maybe you do know!) I would pretty much always choose Versailles 1919 because it’s shorter, more flexible, and easier to teach. But with the right group and the right evening, I would pick Churchill.

Thanks for responding. I now also have to ask, how do you rate Pericles compared to these 2? I’m looking to get one from this series, mostly for solo, but multiplayer will happen occassionally.

I absolutely adore Pericles, although it’s the toughest of the bunch, both to play (it’s under-developed) and to table (it really wants those four players).

Pingback: Review: Versailles 1919:: It’s Pronounced Ver-sah-ay-LEES (a Space-Biff! review) – Indie Games Only

Pingback: Best Week 2020! Some Time Away! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: No Dadbod Without Me | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: El friegaplatos vietnamita – Instituto de Estudios Solarísticos

Pingback: Tube of Treachery | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: SDHistCon 2023 | SPACE-BIFF!