A Triphthong of Word Games

One of my favorite things about playing and critiquing board games is seeing the way designers can push the same mechanism in different directions. It’s not unlike a creative writing exercise in which everybody begins with a single prompt yet still produces their own individual perspective.

Here’s my latest example: I’ve been playing three word games that all revolve around pulling letters, chit-style, from a container. From that sliver of overlap, three distinct titles emerge, each with their own sensibilities and tics. Rather than spreading them across multiple reviews, I figured we might as well see how they fare in the grammar arena, my totally made-up word game deathmatch.

Ten Dollar Words

Designed by Amabel Holland

Amabel Holland’s Ten Dollar Words sounds a lot like a sequel to Five Dollar Words, last year’s Hollandspiele freebie, but it also shares more than a few strands of DNA with Watch Out! That’s a Dracula!, Holland’s bidding game of vampiric real estate and Frankensteins who don’t need anybody to clarify that they’re monsters, thank you very much.

Hold your horses, though, because Ten Dollar Words isn’t nearly as zany as that freebie magnum opus. If anything, its strongest connections to Watch Out! are found in its idiosyncrasy and absence of hand-holding. This is an auction game without guardrails, and Holland is entirely happy to let somebody eke out an early lead or blow their life savings on a pile of useless letters. It also has that trademark Holland cheek. The letter S, for example, is worth a negative dollar. So much for the breezy pluralizations we’ve been slapping onto our words since Scrabble.

The gist goes something like this. Starting with ten discs, each representing a dollar of bidding material, players are presented with four lots of letters. Depending on the orientation in which they were drawn, these letters can be “live,” worth some amount of currency in their own right, or “dead,” still useful for forming words but entirely absent of value. Going around the table, everybody is allowed to bid on these lots, initially wagering only their purple discs, and then later, after they’ve nabbed a few letters of their own, using their live letters to bump their bids upward. After each successful wager, the lots receive an additional letter apiece.

This being a Hollandspiele title, there are wrinkles aplenty. The first one: your bid is no simple dollar amount, but a word spelt via the letters you’ve purchased. Those purple discs act as wilds, although if I’m being honest it feels a scooch silly to open the first round by wagering six discs and having to pair them with a commensurate six-letter word. Regardless, while it might be tempting to nab a high-value lot, one crammed with K, J, V, and Q, the big question is whether you can actually put those letters to any good. That’s a dollar value of eleven — doubled if you can work the Q in there — but good luck spending it all in one place.

Which is a problem, because Holland’s parting quip is that your final score is assessed not by the raw value of everything in your hand, but through your final word. It’s brilliant, as objectives go, if not also somewhat cruel to those of us who agonize over arrangements of letters. Oh, and those purple discs? They disappear from your hand before you cobble together that last word. No more leaning on wildcards in the final stretch.

I’ve never scratched through the dirt to find kernels of corn to assemble the juiciest cob, but I can say with some assurance that that’s what Ten Dollar Words feels like. For better and for worse. On the one hand, this is an unforgiving little ditty, half an hour long, riddled with anxiety, and still liable to produce scores well below that starting ten dollars.

But it’s also wholly unlike anything else out there, a devious alchemizing of both of its genres. One of the joys of word games is persevering through mismatched letters to create words that are surprisingly efficacious. One of the joys of auction games is the way the same goods develop wildly different values to everybody at the table, letting you pick apart those values in order to get the best deals or tank those pursued by your rivals. Ten Dollar Words understands the appeal of both and puts them to work. It’s genius. Also a little bit evil. In the end, perhaps, a game that feels too smart or too far-sighted for my aching brain.

Typeset

Designed by Jasper Beatrix

Part draw-and-write, part press-your-luck, Jasper Beatrix’s Typeset sits in the opposite corner from Ten Dollar Words, approachable in every way that Holland’s title is not, if only because nobody is judging your letter choices.

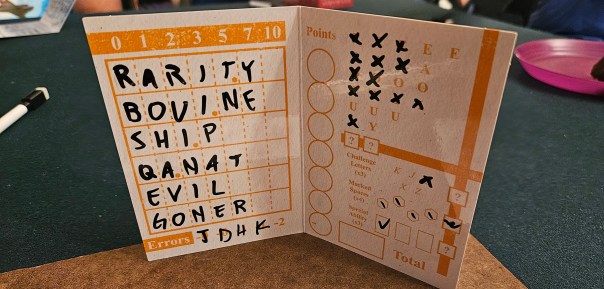

The idea here is that letters are drawn at random and displayed publicly. In the usual draw-and-write fashion, everybody labors from that identical input to craft their own words. Letters are produced in sequences of five, each of which must be penned onto one of the six lines of your personal booklet. There are only consonants this time around — vowels are also available from your booklet, as are wild letters that can be unlocked by using whole columns of vowels or successfully placing challenging Ks and Js or filling up your lines to certain depths.

This is more challenging than it sounds, with words presented as challenges of increasing difficulty. Early on, this is easy enough. You could assign one letter per line, if you really wanted. As successive letters are added, this increases a word’s specificity, and thus lengthens the odds of putting together something workable. Q becomes QAN, but now you need a T to make QANAT, and you’re cursing the day you didn’t use a different vowel to begin with QU instead. Like, QUANT would have used the same consonants and provided an easy fallback, but noooo. Come on, Dan.

You’re free to bow out, securing the values of your words — longer is better, and no, Beatrix doesn’t harbor the same resentment for the letter S — but only after a full tranche of five letters has been doled out. This is the press-your-luck portion of Typeset. It’s tempting to stick around in your quest for the right letter, but doing so risks adding something ill-timed to the back end of a word and reducing it to an illegible (and unscoring) slop.

This does raise one niggle. Each player is permitted a handful of “errors,” which allow you to toss out unwanted letters in exchange for negative points. But it’s easier to allow one of your word lines to become a dumping ground for errant graphemes, a ragged jumble of NTVQXN that, while it doesn’t score when the game concludes, feels contrary to the spirit of the thing. [EDIT: Never mind — jumbled words score negative points! Hallelujah! Niggle resolved. Turns out that Typeset is even better than I initially believed.]

Apart from that, Typeset is filled with affection for moveable type, and Beatrix’s commitment to the bit is admirable. Each session features a special ability, which players may use to bypass the game’s usual restrictions and, once deployed thrice, provides one of those crucial wild letters. Even the act of reading through these cards is pleasingly educational, with Beatrix weaving each concept into the gameplay. Ligatures become free Fs or Ks, Capitals allow one to produce proper nouns, and Translation permits a misspelled word so long as it sounds like a legal word, which strikes this reader of old documents as both accurate and AHHSUM. There are twenty-five abilities in all, each altering the tone of any given session, and not a one of them feels misplaced.

Like many word games, Typeset is a more solitary endeavor than something like Ten Dollar Words. Indeed, it can be played solo as a score-chaser. That doesn’t make it overly gentle. If anything, it’s the most affectionate panel of this triptych, asking players to consider the way words are bound together, to tinker with prefixes and hold out for just one more letter. It doesn’t hurt that one gets to learn a few printing terms along the way.

Typewriter

Designed by Tim Fowers

Tim Fowers is no stranger to hybrid word games. Paperback and Hardback both position spelling within a deck-building framework, while Paperback Adventures, co-designed with Skye Larsen, conceptualizes the freewheeling magic of wordsmithing as attacks and parries in a roguelike adventure. Maybe it’s no surprise, then, that Typewriter feels like the most assured entry in this trilogy, more robust and fully developed than the others. Also, its letters are plastic chips instead of punch-outs. Like the typewriter keys they imitate, they clack so very nicely. Here’s your gold star, Typewriter.

Like our other two entries, Typewriter asks players to draw letters from a bag and arrange them into functioning words. Unlike Ten Dollar Words or Typeset, one has much greater control over which letters they select. This is the least radical of the three, with players nabbing keys from a shifting offer. One is never forced to contend with an errant J, for example.

The composition of those letters, however, is subject to some discussion. Keys are double-sided, and plenty of them sport special abilities on their reverse face. There are wilds, of course, but those are the least interesting options. Some flip other keys. Some let you nab an additional key blindly from the bag. On occasion, one will let you bank a key — an enormous boon, since banking and starring keys is how you win.

This is word-making as engine-building, to lay out the organs of this particular chimera. The higher the value of the keys in your word, the farther you push your typewriter track. This track can be banked for later or cashed in all at once, potentially triggering an entire range of abilities. Wilds! Extra keys! Banking!

In a move redolent of the treasure cards from Valley of the Kings, the toughest decisions in Typewriter revolve around the keys themselves. Once banked, keys now award their value in victory points. These banked keys can later be starred to further bump up their value. Of course, this removes them from circulation altogether. Thence the rub. Should you keep a powerful key around to boost your typewriter or bank it to increase your score? As in Ten Dollar Words, keys are only as useful as the words you actually work them into, so there’s some wiggle room here. Might as well bank that J, is what I’m saying.

The emphasis in Typewriter is more on the engine than the words, although it would be inaccurate to say that the words don’t matter. Hitting high-value keys is worthwhile, and thinking creatively can push your typewriter track across necessary thresholds. Such moments are always thrilling, especially when they dodge the downer of landing one keystroke shy of a particular bonus.

It’s also nice to see Fowers solve one of the problems that has dogged his other word games. Your letter pool is simply more dynamic than elsewhere. Every turn lets you claim at least one key, and thanks to their double-sided nature even that one acquisition often has far-reaching implications. Your collection is in a constant state of turnover, sidestepping the possibility of crafting the same words over and over again.

The result is a solid word game and engine-builder. It lacks the radical highs of Ten Dollar Words or Typeset, but sports an enviable degree of polish. More importantly, it demonstrates that Fowers and Larsen can continue to push their craft in new directions.

There you have it. Three word games, all of which feature chit-pull letter selection, but couldn’t feel more different. They’re so distinct from one another, in fact, that I struggle to choose a favorite. Okay, it’s Typeset. That’s my favorite. Still! Each of these titles offers its own perspective on how words can be assembled, its own quirks, even its own remediations on a genre that’s been well-furrowed. There’s a reason I’m still playing word games after all these years.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

Complimentary copies of all three games were provided by their respective publishers.

Posted on October 8, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Amabel Holland, Board Games, DVC Games, Fowers Games, Hollandspiele, Ten Dollar Words, Tim Fowers, Typeset, Typewriter. Bookmark the permalink. 18 Comments.

A real orthographic onslaught here.

Kablammo!

I loved word games growing up, something though that changed that a bit was having a partner for whom English is a second language. From no fault of the genre, that kinda took word games to a place that evoked distance rather than closeness. I’m sure that’s not a universal experience, but I still miss the easy pull of a scrabble of a boggle. I guess I haven’t thought about whether there’s any polyglot word games out there.

That’s definitely a limitation of the genre! I find that we always spend at least a few minutes grousing about what qualifies as an acceptable word. For what it’s worth, Amabel Holland doesn’t prohibit proper nouns in Ten Dollar Words, and I imagine any of these games could be played with multiple languages.

The biggest issue with trying to play an English-language word game in another language is letter distribution.

As a Norwegian, many words are simply impossible to write without Æ, Ø and Å (other languages are missing other letters). But even ignoring all words which include non-English letters, game balance is turned on its head completely.

Several letters which are very common in English are near impossible to use in Norwegian (e.g. W, C, Q, Z, X), while the supply of certain letters which are ubiquitous in the Norwegian dictionary is far too small…

This is made even worse in games where you score points based on the difficulty of using a letter, which is not consistent between languages even when they share an alphabet.

For mass market games like Scrabble, this isn’t an issue – you simply buy a translated version. But for designer board games, you either play them in English or you don’t play them at all.

This didn’t bother me much before, but after having children (including one with special needs), I’m no longer in the market for English-only word games.

For my boyfriend and me, it’s similar. English is actually a second language for both of us, but I’m better at languages than he is and he refuses to play competitive word games against me. We play a lot of Hardback and Paperback in the respective cooperative variants though, which we both enjoy, so perhaps that would be something you could try with your partner? I haven’t tried Typewriter yet and I’m not sure I will soon, since it doesn’t seem to have a cooperative variant.

While I love word games, I’ve always put spelling games in the same category as trivia games. But, my father and brother like them, so I’m always on the search for the ones I find bearable. Handsome is my current go to if go I must.

Mind, seeing as I play games with people fluent in English, French, or Spanish, neither word nor spelling games are really something I want cluttering up my games closet.

That jumble picture compels me to try to find the best Boggle word in it all, with the restriction that all 3 games’ tokens must be used. (Just using the main letter on the side facing up.) “Parkade” is the best I can find, using more-or-less adjacent tiles. “Caudex” seems decent, too — since it uses an X.

Ha, nice challenge!

It’s games all the way down.

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Combined! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: A Desire for More Cows | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Here Lies Every Other Detective Game | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Fear Factory | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Whispers-in-Leaves | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Categorize My Thing Thing | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Most Select of Board Games | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: PHANTO | SPACE-BIFF!