Red Fish, Blue Fish, Fish What’s Ticklish

Comedy is hard, and that goes double in a medium with no clear speaker and a tendency toward the pedantic. Who’s on first? That guy. The guy who just batted a single. Obviously.

Fortunately, Things in Rings has what we call pedigree. Peter Hayward is a funny fellow, especially when he’s designing games like That Time You Killed Me or Fiction. Even this year’s Converge hits the right beats gameplay-wise to nearly qualify.

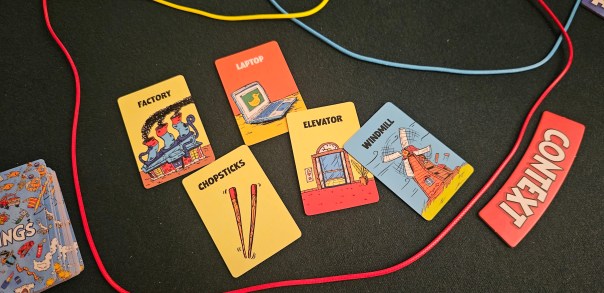

As you may have deduced, Things in Rings could have been given the not-as-rhyming title of Venn Diagram: The Board Game. Players are tasked with sorting cards (the titular things) into various compartments (the aforementioned rings). The hitch is that you aren’t sure what any of the rings are actually supposed to contain.

Hayward isn’t the first person to receive this particular stroke of inspiration. Matt Leacock tried it in 2016 with Knit Wit, a game I broadly enjoyed. But it isn’t a radical statement to say that Things in Rings is the better game, in no small part because it leans more deeply into the innate humor of its situation rather than relying on walnut spools and big painted buttons. This is a game meant to be played, not admired.

By which I mean, Things in Rings isn’t about sorting things into neat categories. Oh no. It’s about cramming objects into categories that can barely contain them. It’s the board game version of angling a couch up three winding flights of stairs only to realize that the apartment it needs to squeeze into doesn’t have a large enough door. One could find such an occurrence consternating. Depending on the day and how badly one’s forearms are aching, sometimes that’s as good as it gets. But there’s also an innate physical humor to such a moment, a wild laughter that blunts the frustration.

That’s Things in Rings in a nutshell. With the wrong attitude, it’s curiously frustrating. It takes some effort. But the effort is worth the while.

In each session, somebody is the knower. This is the person who arranges the rings and knows what each one is supposed to contain. It’s possible to play with fewer than three rings, but come on, you aren’t here for that. Anyway, this is a game that works best when it’s maximally frustrating. The more noise it produces, the more it sings.

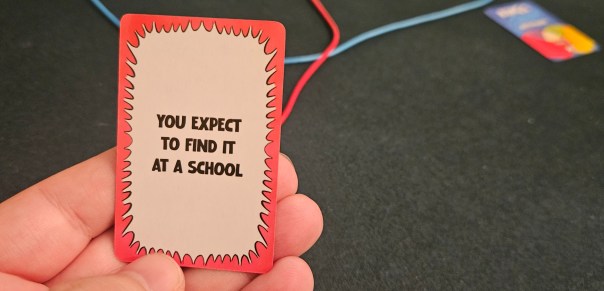

Every ring has its own motif. The blue ring, for instance, speaks to an item’s attributes. “Would hurt if dropped on you,” reads one card. “Flammable,” reads another. Now, the astute among us have already seen the problem. These are subjective! Anything might hurt if dropped on you! Anything is flammable with enough effort! True enough. Such relativism is dimmed with the yellow ring. These are all about a word’s grammatical arrangement: one syllable, longer than seven letters, a compound word, that sort of thing. But then we come back around to the red ring. These are the item’s context. “Most people have this at home,” perhaps, or “you can find it within an hour from here.” The problem rears its head again.

Okay, so the distinction between the blue and red rings is fuzzy. Worse, there’s quite a bit of wiggle room inside the categories themselves. What’s a person to do?

Experiment. That’s all there is for it. On your go, you place a card somewhere within the rings. Or outside of the rings if there’s no place for the object inside of them. The knower then does one of two things. Either they acknowledge you’ve made a correct guess, which allows you to take another turn, or they shift your card into its proper position and give you a new item from the deck.

This last outcome is a failure. Only it isn’t quite a failure. It’s a data point. It’s a clue for everyone at the table.

It’s also sublime existential comedy.

Longtime readers will know that I sometimes suffer from a certain degree of solipsistic dread. On occasion, reality feels very unreal to me, not quite firm, things and concepts and, yes, sometimes people not sorting as neatly into their proper boxes as I would prefer. Like the couch at the precipice of our apartment, this is one of those laugh-or-cry moments. One either despairs of ever figuring it out, life and everything else, or learns to revel in its messiness.

The flimsiness of Things in Rings’ categories sounds like a problem. It is a problem if you want a game that’s solely about deduction. But it’s a beautiful problem, a human problem. Because even the knower is playing the game. They aren’t some robot, sorting cards according to concrete properties. They’re also grappling with what these words mean. Like the askers, the knower is also trying to decide whether a ghost should be considered dangerous, or how many holes the Necronomicon has, or whether a pillow contains plastic. We quibble about definitions because they’re useful. But they’re also pretend.

Those moments of failure, then, are a glimpse into the knower’s all-knowing mind. Their some-knowing mind. This is the contentious kernel of Things in Rings, the hinge upon which it turns, the watershed that will divide those who appreciate it from those who can’t stand it. Because while this is a game about objects and attributes, it’s also a game about our flawed, one might even say doomed, efforts to compartmentalize the world around us into tidy boxes. Not coincidentally, it’s often a winning strategy to start dumping your most confounding cards into the gray area outside of the rings.

In the end, Hayward has created something as baffling as those tentative early steps at pinning down a clue. Things in Rings is funny and frustrating, baffling and waggish, perhaps too empirical for most party gamers but too flimsy to be considered serious. It doesn’t fit neatly into a box. I think that might be my favorite thing about it. There’s no higher compliment.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on October 7, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Allplay, Board Games, Things in Rings. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

I love the way you make this review into pondering on D. Adams thought experiment on couches being-in-the-world-iness.

And can’t wait to try this newly acquired game as soon as I find a way to be on the couch in the stairwell and at the table with the game, at the same time.

Thanks! I hope you enjoy the game as much as I have.

Pingback: Strip Poker | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Combined! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Categorize My Thing Thing | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Sporks | SPACE-BIFF!