Anthropic Rock Collector

Sea glass is the second coolest anthropic rock, ranked right behind fordite and waaaay above concrete. River Valley Glassworks, Adam Hill, Ben Pinchback, and Matt Riddle’s hot game of the moment, is about cute river creatures collecting fragments of discarded glass that have been tumbled smooth by the river. As befits the man-made artifacts you’re collecting, it’s wonderful to look at and feels incredible to manipulate. It’s also a little too superficial for my tastes.

To be clear, there’s a difference between “simple” and “superficial.” The first is desirable; the latter, a pickle. River Valley Glassworks falls into both categories. Its rules fit comfortably onto a single glossy sheet. Explaining the game takes all of two minutes. My five-year-old can play without violating any rules. My ten-year-old can formulate a strategy.

But that’s also part of what makes the game superficial. This is a game with all of one approach, a best practices list with exactly one bullet point. That, too, is fine. Plenty of good games are about doing one thing as optimally as possible. The problem with River Valley Glassworks is that it veers between one mode and another, between careful planning and outright chance, without being flexible enough to sustain both at once.

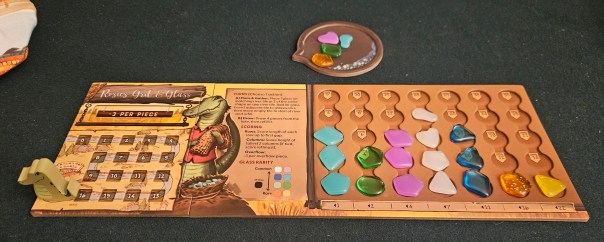

Let’s back up. River Valley Glassworks is about moving glass from one place to another. There are four places glass might occupy. Your pan, where glass functions as currency. The lake, which is a pool for gathering glass into your pan. The river, where you deposit either one or two pieces of glass from your pan to collect other pieces of glass. And lastly your glassworks, where the glass you collect from the river is stacked and lined up for the sake of scoring. The life-cycle of spent Coke bottles and table lamps.

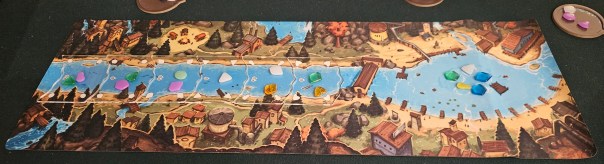

The smartest of these locales is the river, an ever-shifting and ever-modulating offer of glass. Allplay’s production is terrific, presenting the river as six transparent trays that allow glass to be shifted back and forth without a burdensome amount of scooting too many pieces across the mat. To collect glass, you place a piece from your pan into the river and then claim all the glass in an adjacent space. The need to match your glass to the imprint shown on the river prevents this process from being too flippant; alternatively, you can burn an extra piece of glass to place two identical shapes onto any tray you want, bypassing the restriction altogether. The glass you just placed is now part of the river’s bounty for someone else to collect, while the now-empty tray is shifted to the top of the river and refilled with random shards of glass.

Your collected glass is worth victory points. The final rubric is refreshingly simple. You lose points for extra shards of glass, preventing players from gobbling up too much junk. You earn points depending on how full your rows are, a question of collecting many different colors of glass. You also score your two highest piles of like-colored glass. Because glass comes in a handful of rarities, and because “later” piles are worth more points than the ones you can stack up earlier, and because ties are broken leftward to favor the lower-scoring piles, a general rule of thumb is to collect rare glasses early and the more common stuff later on. Blur your eyes and a winning combination looks like an upward-trending bar graph.

Like I said, it’s pleasingly simple. It also feels good in motion. The real highlight is the river itself, as clever, fast, and dynamic a market as there ever was, and despite threatening to overwhelm with its constant upkeep, everything has been produced so carefully that it never stops feeling good on the fingertips. In the game’s back half especially, choosing which stretch of river to dredge is anything but easy. With some experience, it even produces a few minor opportunities to poison the well. If the player next in turn order would benefit from the color of glass you’re thinking of throwing into the river, maybe it’s worthwhile to toss in something else, or add that glass to a tray that would also subtract a few points from their final tally. What initially feels too simple soon reveals additional depth.

But it also bottoms out again thanks to the game’s over-reliance on baggie draws. It’s one thing to refresh the lake; players choose when to draw new glass, giving them a measure of control over their fate. In other circumstances, however, the whims of the bag can throw the best-laid plans into disarray.

The worst offender bursts into the game in its final moments. As soon as somebody accumulates seventeen pieces of glass, the endgame is triggered. The current round wraps up, everybody gets one more turn after that, and then it’s gently wafting curtains. But the instant that trigger is pulled, everybody whose pan has fewer than four or five pieces of glass gets to draw back up to three pieces from the bag. This bypasses anything resembling planning. Much of the game moves to a particular rhythm, one of keeping your pan full enough to make good selections at the river without refilling so often that you waste time or send too much glass to your overflow. That’s thrown into disarray by a late-game draw. Even more rotten, one player’s newly drawn glass might be perfect for their intended selections while everybody else’s are subpar. Given the tightness of the game’s final scoring, this is often enough to decide the entire session on a single draw.

Of course, this is a breezy enough game otherwise. But it isn’t breezy in the sense that it’s a game of chance. It’s breezy the way Michael Kiesling’s Azul is breezy. Both games occupy a similar headspace, one that wants to be both light and thinky. At times, the similarities are striking. In contrast to Azul, though, River Valley Glassworks is so insistent on keeping everybody’s scores and in-game opportunities clustered that it winds up feeling facile and unimpactful. It rewards those who play broadly over those who play tactically. By trying to ensure that nobody misses out, it flips the script until we’ve all missed out.

As I noted earlier, I’ve had some lovely sessions of River Valley Glassworks. This is the sort of game I want to love, a bijou-filled bijou that actually tricks me into caring about sparkly objects.

In the end, that potential only deepens my disappointment. River Valley Glassworks is very nearly there. But it ends with a fumble. Right as its decisions start to become tricky, it slams to a conclusion, and not always for the one who played it best. If you need me, I’ll be tiling my walls instead of dredging the river.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on August 21, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Allplay, Board Games, River Valley Glassworks. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

This has so many similarities to Subastral also by the same designers. I do find myself like]ing that one more than this, for the reasons you mention. Sure,there’s randomness (it’s a card game), but none of the big randomness at the end that this game has.

Still, I enjoyed my play and would play again.

Interesting! Maybe I should give it a try.

Yes, the scoring is exactly the same (per row and then two tallest columns), but the cards make the actual mechanics of the game different.

I recommend it! It’s a very good game.

I played a few games of this on BGA while it was on Kickstarter and had similar feelings about the game play. And then I saw the actual game in recent GenCon photos and immediately went “oooh shiny rocks!”

I think if I see it at my FLGS library, I might play it with friends there, and I wouldn’t walk away from the table if someone set it up, but I don’t need it…even if the rocks are cool. But, as you mentioned, the shiny rocks might be a great way to get younger players or reluctant not-quite-gamers to the table.

I like what Allplay is publishing right now – their games are beautifully packaged and easy to get on the table, but outside of a few notable exceptions most of what I’ve played fall into the ‘good, not great’ category.

Also, clearly the rightmost column is Fresca!

Ooh, good pick!

Yeah, I really dig what Allplay is doing with some of their releases. Their production of Sail is wonderful, A Message from the Stars is fantastic, and I have an abiding love for Bites. But “good, not great” seems like an apt description of most of their catalog.