Ars Wilmot

Meet Wilmot’s Warehouse. Based on the video game by Richard Hogg and Ricky Haggett, and designed by David King — creator of browser-based roll-and-write Tiny Islands — Wilmot’s Warehouse is a memory game. Let me finish! Wilmot’s Warehouse is a memory game but good. But great. But excellent. But a minor miracle, a religious experience, a paean to human creativity in an era where tech grifters believe the species ought to be replaced by expensive imitation engines.

I’m going to tell you a story.

As I sat down to write this review, my five-year-old walked up to my desk. She never shows much interest in what’s on my computer screen. It’s all words and shapes to her. Words she can’t read. Shapes of board games she can’t play. Today, instead of going through the usual morning routine of saying she’s hungry but not having any ideas for what she wants for breakfast, she paused. She stareed at the screen for a solid twenty seconds. Then she sprinted to the board game table. She tapped Wilmot’s Warehouse on the lid and asked, “Daddy? Can we play the game? The game about the man finding boxes? The game about the funny pictures?”

This isn’t the first time CMYK has published something that appeals to my kiddos. There’s Wavelength, a gadget game about the weirdness and approximateness of words. Spots, with its canine-imitating cow, butthole-baring doggo, and sensible dice odds. Lacuna, as close to a platonic ideal as a real-space game gets, with its matching and measuring and nail-biting tiebreaker. I’m tempted to mention Daybreak, too. Not because my kids have played it. Just because Daybreak is really good.

Now my five-year-old is sprawled on top of the game table, and she is hugging Wilmot’s Warehouse. I know that sounds fake. On social media, there would be a punchline. Something contrived. My five-year-old would turn her face up and say, “Daddy, if taxation is theft, then who is the guarantor of natural property rights?” But nothing like that has happened. She’s just lying there, head rested atop the box, arms wrapped around it like it’s her favorite kitty stuffy. I don’t think she even loves me that much.

I’m going to tell you a story.

Wilmot’s Warehouse is about placing tiles on a grid and then trying to remember where you put them. The video game is also about that. But it’s about motion, too, and fulfilling complex orders, and Wilmot’s boxy face exerting a droplet of sweat as he drags too many pallets from one location to another. When I received the email announcing the game, I had my doubts. How could they adapt such a thing? I accepted a review copy out of sheer curiosity.

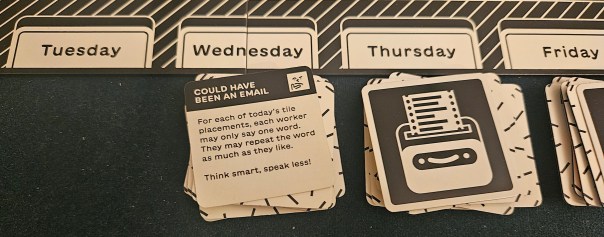

Ten minutes into our second session — ten minutes is maybe half of a full play — we were stymied. Every so often, you reveal a card that complicates the usual tile-placing regimen. This one announced that we would be placing tiles off to the side of the board, seven of them in sequence, rather than fitting them into the expanding warehouse.

Wilmot’s Warehouse, you see, is a game about telling stories through interpretation and proximity. If our first tile is a beehive, it becomes the centerpiece of an explanation about where and why the other tiles have come to be placed around it. A striped egg: it was laid in the same tree as the beehive. A thumbs-up: this orchard’s dual apiarist/ornithologist can’t believe his good fortune. A… whistle? Is that a whistle? Or perhaps a grace note? An impressionistic snail? Let’s go with a snail. We place the snail below the beehive, one more garden wanderer.

The trick is that tiles are placed face-down. The stories you tell serve as reminders of what has been placed where. I bet you can name the items from the above paragraph: beehive, egg, thumb, snail. When the game reaches its final beat, you rip through a massive deck of cards, one for each of the tiles in the bag, in an attempt to match cards to tiles. There are 150 in all, but you will only place thirty-five in a session. Most of the cards, then, are for things you have not seen today. You match as fast as you can. You throw away any cards that are not located in your warehouse. The ones you remember, you place atop the tiles. You retell the stories in your mind. Out of order, fragmentary, but still present.

Back to that stymieing card. We were forced to place seven tiles off the board. Outside of the story we’d been painstakingly telling for twenty-ish tiles. One by one, the tiles told their own story. A pig snout: okay, there’s a pig. A skull: and the pig died! Something shaped like a coffin: easy, we buried the pig with full military honors. But then a striped brown slab: oh no. Bacon. We were desperate.

That’s all there is to it. Story. Narrative. Memory. Coherent and whole. I remember that sequence of cards even now, a full month after that session. I’m sure there are imperfections in my recollection. Some of the cards have gone missing. The sequence might not be totally right. But it’s there. It’s as much a part of me as anything.

I’m going to tell you a story.

When I was young, I was interested in ars memoriae, the Art of Memory, that ancient practice by which a person could recall complex strings of information by attaching them to a familiar mental image. I built a mind palace for myself. Not one mind palace but many, a dozen constructs in sequence. The entryway was my grandfather’s house. I can smell it now, each room its own identity, filled with the artifacts of my childhood. I filled those halls with poetry, with language. I can still walk through the house and recall snippets I placed there when I was fifteen.

I tested very well in high school and college. That’s probably the sum benefit of all that effort. When a professor said that a test would be open book, I felt a little salty about it.

The beauty of ars memoriae isn’t that it’s difficult. It’s that it’s easy. You learn to do formally what we all do naturally. You imagine a place and then fill it with details, vivid images, smells, feelings, people. Which is precisely how we remember anyway. I remember the crinkle of my grandmother’s hand in the hospital bed. I remember where my wife uncovered petrified cat droppings above the cupboards of the duplex where we first moved in together. I remember every corridor of my high school, now thankfully torn down. Those spaces are already brimming with memories. Brimming with stories. Ars memoriae is about using those spaces to remember, I dunno, historical dates. The periodic table. Koine Greek. Sheet music. Whatever you like.

The beauty of Wilmot’s Warehouse isn’t that it’s difficult. It’s that it’s easy. When you peel through that deck, it’s incredible how quickly you recall what goes where. It feels like a miracle.

But the miracle of Wilmot’s Warehouse isn’t that you put thirty-five tiles onto a grid and then remember their precise location. No. That’s what it tells you. But that’s a magic trick, not the magic itself. The miracle of Wilmot’s Warehouse is that it reminds us that we are storytellers. We are homo sapiens, the wise ape, homo ludens, the ape that plays, homo narrans, the ape that speaks in tales. Wilmot’s Warehouse doesn’t work because it has us do something new. It works because it has us do something we were doing all along. It reveals that the miracle is us. You. Me. Those kids. Every one of us.

Right now, my daughters are telling a story.

I started writing this review forty-seven minutes ago. My five-year-old saw the images of Wilmot’s Warehouse on the computer screen and asked to play. Ever since, I’ve been fending her off. “I can play as soon as I finish writing this,” I said. “Just a little bit longer.” She woke up her sister to announce we would be playing the game about the man with the boxes. She asked how long it takes to write an article. She’s too young to understand time, so she asked again less than a paragraph later. She announced that it’s boring when I work. Sometimes I agree with her.

Now we’re going to play Wilmot’s Warehouse again. The girls have already put the board on the table and are rifling through the bag, insisting that we use a worm as our starting tile. This, too, will become part of our story. I think it’s a good one.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on August 6, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, CMYK, Wilmot's Warehouse. Bookmark the permalink. 18 Comments.

That…was beautiful

Thanks!

Such a wholesome and personal review: joy aplenty!

I cannot wait untill my daughter is 5… And I want to teach her the joy of organising – with Wilmot’s Warehouse.

Having kiddos old enough to play board games is truly a delight!

I loved the videogame based on Matt Lees suggestion so I imagined I might enjoy the board game too… but your review is so lacquered with this wholesome connection that I think it’s what has tipped me over the edge into looking to get a copy.

I am not a parent, yet, but planning for one in the near future – so these anecdotes of familial fun were really delightful and inspiring to read. Thank you, Thurot family!

Thanks for the kind words, and best of luck in your family planning!

I’m still gonna doubt that I’ll enjoy a memory game, but I have so much affection for the video game that it makes me happy that the cardboard version stands on its own merits. There’s something magical in how the video game exposes how you make associations, and I’m glad that’s what the board game seems to have honed in on.

Yeah. I was worried the board game would focus on the mechanical actions of the video game, physically moving things from point A to point B, because that would be a chore. Instead, King has isolated the essential kernel of what made the video game worthwhile.

What a lovely review! Thank you for this!

Thanks for reading!

Wonderfully written. Excited to play this with my kids as well!

Thanks, Kristoffer!

Pingback: Space-Cast! #41. Wilmot’s Island | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: The Gooey Decimal System | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: That’s Not Two Minds! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Adapted! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Magenta One: Fives | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Summer Ludens | SPACE-BIFF!