Scratch & Sniffle

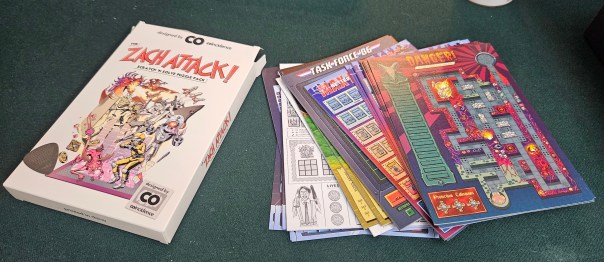

Now here’s something I haven’t seen before: a collection of six scratch-off board games designed by puzzle master Zach Barth. That’s a sentence that keeps getting more intriguing as it goes, especially after The Lucky Seven proved one of the most reliable single-deck solitaire games on my shelf.

What I didn’t expect was the smell. I don’t know how scratch-offs are made, especially scratch-offs as nice as the ones in this pack. These are hardly the state fair scratch-offs from my childhood. They still produce a royal mess — I’ve had to play with a little rubbish can next to the table — but that metallic scent has proven strangely addictive. Is this why people gamble away their life savings? Maybe I’d be tempted to do so as well, were the minigames in the state lottery this compelling. Let’s run through all six.

Danger! In the Temple of Malice

The first title is a nifty press-your-luck ditty that keeps the rules light, marking it as a perfect entry point to the collection. It’s basically a roll-and-move, except in place of rolls there are scratch-off boxes. You reveal the three numbers in a box, take those moves in any order — while potentially skipping any digits that strike you as unwise — and hopefully reach the end with as many medallions as possible.

That’s more or less the entire thing, although of course there are a few dueling considerations to keep in mind. The first is your own mortality. Stepping on three traps will spell an early end for your delve, and of course they’re everywhere. Some are duds, which is always a relief, especially near the end of the temple where it isn’t uncommon to see them clustered together. Meanwhile, you also need to reach the end of the track, navigate the occasional branching path, and take calculated risks to secure as much loot as possible.

Danger! is a simple thing, but it sets the tone for the entire collection. On the positive side, these are bite-sized puzzles that use familiar systems in fresh ways, often putting the limitations of their medium — laminated scratch-off pads — to work in interesting ways. It’s impressive to see how far afield Barth is able to wander within these constraints.

But there are more frustrating points as well. Danger! sets a precedent that will crop up more than once throughout the collection. Namely, the possibility of concluding a pad before it’s been exhausted. The box contains ten sheets per puzzle. That’s more generous than I expected, but it still turns them into a precious commodity. While the sheets’ limited quantity provides some additional motivation to consider each step before committing dime to ink, it can still prove deflating when an early misstep threatens to waste the entire puzzle.

Fortunately, that possibility is fairly remote in Danger! thanks to some eminently clear stakes. The ability to decline a move ensures you’re never cornered, even as it threatens to leave you a few steps short of the exit. On the whole, a solid opening gambit for the collection.

Task Force ’86

And then there’s the deep end of the pool. Also known as the ocean. Task Force ’86 is an homage to Battleship, but it understands that having too many empty spaces is boring, so instead it fills the sea with not only enemy ships to pick apart with long-range strikes but also a very good chance that every move will result in total disaster.

Your goal is to hit every segment of every enemy ship. There’s a rubric for these things: the enemy fleet contains one battlecruiser, which must be situated entirely in deep water, four shallow-water frigates, and a handful of cruisers and destroyers that might be scattered between the sheet’s halves. Missiles appear around these vessels’ edges, both hinting at their position and threatening to strike your fleet.

Speaking of your fleet, Task Force ’86 introduces a concept that will be present in nearly every other entry in the collection: a small number of bonus resources that can be spent at watershed moments to turn the tables in your favor. While you’re free to scour the ocean for enemy vessels however you see fit, this objective is made easier by your fleet of five friendlies. Your destroyers provide helicopter sorties, which reveal a bunch of cells in a line but stop as soon as they encounter a missile or submarine, while your aircraft carrier holds strike fighters that blow up an entire 3×3 square, and your missile cruiser packs a pair of counter-missiles. This last option is crucial. When revealed on the map, enemy missiles sink your ships, by extension stripping away your bonus powers. That is, unless you knock down the incoming attack.

The inclusion of these limited resources is what makes Task Force ’86 one of the collection’s most gripping puzzles. It’s a big leap from Danger!, complexity-wise, but the tradeoffs are significant. Every space feels dangerous, and it takes real contemplation to choose between launching an air strike or another reconnaissance mission. As puzzles go, this might even be my favorite entry in the whole package, a perfect blend of Minesweeper and the tension that comes from having to physically reveal each cell. This is the good stuff.

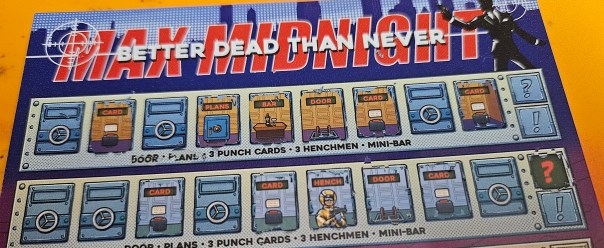

Max Midnight: Better Dead Than Never

Blending bad puns, Roger Moore-era James Bond, and aesthetics that remind me of nothing more than Apogee’s Secret Agent, Max Midnight is all about diving into an evil mastermind’s evil lair to undo their evil plot before a bunch of people are killed, evilly. He’s the hero we need in this day and age, that Max Midnight.

On the surface, Max Midnight is one of the collection’s chancier titles. You progress through the lair one floor at a time, scratching off doors to reveal what lies inside. The mission is to find enough punchcards to deactivate the control panel on the bottom floor, although this is complicated by henchmen and robots that first raise the floor’s suspicion and then shoot you dead. Early fails are a real possibility.

Except the inclusion of a few critical tools makes Max Midnight a fairly easy puzzle overall. Your agent has a limited number of bullets for shooting henchmen, plus a laser pen that can tunnel deeper into the base. Oh, and some X-ray glasses. This latter tool is my favorite, and it’s complemented by secret plans that can be stumbled upon as you search the base. Their effect is identical: you scratch off a door’s “window,” revealing what’s hidden inside without actually popping the hatch. This allows Max to perform some light surveillance before committing to any given door.

Meanwhile, there’s another rubric to consider. No two adjacent rooms contain the same feature. While an early misstep might see you bumbling into a henchman, this also proves a learning experience, since the doors up and down the hall are guaranteed to be secure. Until you reach the floors with the killer robots, anyway.

On the whole, Max Midnight is one of the more throwaway titles in the collection. It’s cute and whimsical, but lacks the dense thinkiness of its peers. Then again, it gets serious bonus points for the whole “look through the window” feature, which Barth will repeat in a later entry. I appreciate any game that leans into its inherent strengths, and letting players peek at a space without revealing it entirely is a very cool way to use the scratch-off concept.

Signal to Noise

Ah, more Minesweeper. Fortunately, I like Minsweeper (and nonograms). Also, it helps that Barth knows how to tinker with the formula to produce a puzzle that invokes the familiar while also feeling entirely new.

Signal to Noise is a digital heist. Most spaces contain cash; the rest represent ICE that threaten to trace your location. In Minesweeper terms, these are the bombs. But in a total inversion, only bombs reveal the adjacency of other bombs. Cash itself is only useful for scoring. When it comes to data-mining, they’re effectively blank.

The solution lies in the game’s limited resources. Here these are Data Miner and ICE Breaker programs, both of which allow the player to string together many reveals of either cash or ICE spaces, but only until they hit the other type. To once again use Minesweeper terms, it’s as though you could switch into “bomb mode” to click as many bombs as you want, but only until you accidentally hit an open cell again.

At the same time, you’re provided hints as to how many bombs are located in each row and column. Often, this is scant information. Most of the sheet’s grids are wide-open spaces, forcing some exploratory scrapes before the process of deduction can begin in earnest. This poses some interesting questions about how to manage risk and your programs, but it also reminded me of a crummy version of Minesweeper on an old TI-86+ where the first click wasn’t a freebie, often resulting in more frustration than anything.

Still, Signal to Noise is a strong option thanks largely to its final data vault. This is where Barth cuts loose with the odds, presenting a box that’s stacked with ICE on one side and cash on the other. This allows for some truly devious deduction, especially if you’ve preserved enough ICE Breakers to pick through the static. It’s a strong crescendo, although I was left wishing the entire sheet had leaned into that format rather than saving it for the very end.

Dragons Over Dunkirk

In a very nerdy collection, Dragons Over Dunkirk is the sheet that feels most like a thirteen-year-old boy’s mashup of two different sets of toys. It’s commandos versus dragons. Oh, and the commando squad includes a Playmobil firefighter.

This time, Barth adds some time pressure to great effect. Your squad has three days to wipe out six dragon nests, at least half of which are concealed in a cave system, using, you guessed it, some Minesweeper/Hexcells adjacency deduction. That three-day limit is the real highlight, refreshing each squaddie’s health and kit, but not their mortal coil if they happen to have shuffled off it.

And your tools are essential. The Commander carries an infrared scope that peeks at tiles — shades of Max Midnight! — while the Grenadier and Gunner decrease how many injuries the squad takes from a dragon attack. The firefighter, meanwhile, lets you skip over a space, useful for when you don’t want to weather an obvious ambush in between you and a target.

This time around, the cell-scratching is complicated by the fact that your squad absorbs the damage from any dragons they reveal. At the same time, only the most dangerous dragons will lead you to their nests. So the game quickly becomes about measuring how much punishment you can take before you start losing men.

It’s clever stuff, but this is also where the scratch-off gimmick starts to show its seams. There’s more clutter than in previous titles, and the logic puzzle isn’t quite as clean as its peers. In theory there’s an interesting tension between resting or pressing on, except it’s pretty obvious when your squad has taken enough of a beating. Still, it’s an honest-to-goodness squad management game on a scratch-off sheet. I’m less inclined to revisit this one in the future, but there’s still something impressive about how many systems Barth has folded together.

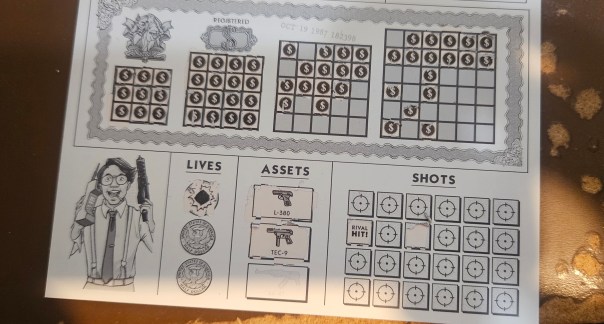

Capital Offense

Finally, there’s Capital Offense. Like everything else in Zach Attack!, this one contains fifty shades of press-your-luck, but its more notable inclusion is shape-building. As a corrupt stockbroker, you’re here to uncover various stocks and then scratch their shapes into four grids. Fill them in to get rich quick. It’s the American Dream as a scratch-off, which is as close as the collection gets to commentary.

Along the way, you might stumble across a baggie of coke or a rival broker. Those rivals turn the game over to a shootout minigame, where you reveal cells on a shot grid based on how many weapons you’ve purchased with your ill-gotten gains. This ups the pressure to fill in one of those scoring boxes early rather than spacing out your stock-shapes in a more sensical manner. As for the coke, it exists to let you fill in a box without worrying about the consequences. Because it’s coke.

My problem with Capital Offense has entirely to do with how its shapes are arranged. Rather than using polyominoes or other common shapes, these ones are all over the place. It feels like I should chart out their possible arrangements before playing, or as if there’s a prescribed optimal solution. I recognize how the sheet wants you to accidentally preclude the possibility of not filling in every square, but it winds up feeling overly restrictive and finicky. It’s also the tonal opposite of the coke-snorting rival-shooting madhouse that marks the rest of the puzzle.

Whatever the reason, Capital Offense is the entry I liked least. It probably doesn’t help that its drab white aesthetic doesn’t capture the sheer vibrancy that’s on display elsewhere. Every time I’ve completed it, I’ve immediately wanted to circle back to one of the other sheets for a refresher.

All told, Zach Attack! is a worthwhile experiment. Half of the puzzles are excellent, only one of them left me cold, and there’s no denying that they’re inventive and clever. Barth has a long history of crafting solid solitaire games, and this collection demonstrates why he’s a master of the field. Operating under the strangest of self-imposed limitations, he’s created six distinct puzzles that each leverage the concept of scratch-offs-as-board-games to their utter extreme. I would love to see another set in the future. For now, I’ll be merrily scratching away at Task Force ’86.

A complimentary copy of Zach Attack! was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read about which films I watched in 2025, including some brief thoughts on each. That’s 44 movies! That’s a lot, unless you see, like, 45 or more movies in a year!)

Posted on January 20, 2026, in Board Game and tagged Alone Time, Board Games, Coincidence, Zach Attack!. Bookmark the permalink. 3 Comments.

So cool! I’m itching to scratch.

Super intriguing!

Pingback: Space-Cast! #53. Scratch & Listen | SPACE-BIFF!