Legend Became Tabletop

Countless players and critics have already pointed out that Matt Leacock’s Fate of the Fellowship is magnificent, and there will be no hot takes here. I’d call it the finest Lord of the Rings board game ever made, but I still have War of the Ring sitting unplayed on a shelf somewhere, and anyway there are so many wonderful tabletop adaptations of J.R.R. Tolkien’s trilogy that any quibbles would be matters of taste more than quality.

What impresses me the most is the granular stuff. The sheer amount of love poured into the adaptation, of course, but also the way Leacock has refined his original Pandemic formula until it’s all but unrecognizable. The crucial elements are present, but Fate is so far removed from that disease-inoculating 2008 original that it’s like observing evolution in freeze-frame.

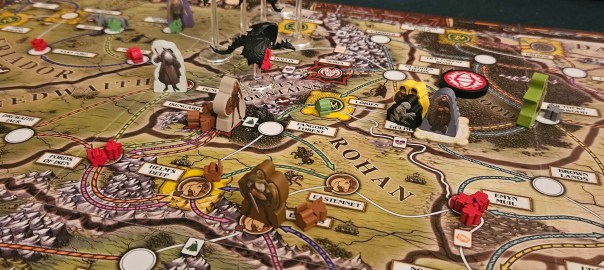

From an eagle’s perspective, Fate of the Fellowship presents the same Middle-earth we’ve seen countless times before, maybe with a few lines squiggled differently here or there, but still more familiar than one’s neighboring counties. Apart from the usual region boundaries, the map is dominated by lines denoting adjacencies. These are the routes your characters will traverse, both as they guide the One Ring to Mount Doom and as they muster and lead armies into battle. More than that, though, these are the routes Sauron’s hordes will follow across the land.

On the map itself, this is as close as Leacock gets to Pandemic, and it’s distant enough to require some squinting to see Fate’s parentage. Orcish hordes amass and march, but they never spill over in the fashion of Pandemic’s disease cubes. Indeed, they’re organic in a different direction entirely, sometimes veering one way or the other, zigging when you expect them to zag, and fostering an invasion plan that can be predicted but not always with complete accuracy.

This trend — of modifying Pandemic, but doing so in ways that are not only unexpected, but to some degree counterintuitive to what veterans will expect — quickly becomes the game’s hallmark, at least for those who are here more for Pandemic than for the hobbits and ringwraiths. Shadow cards sometimes raise baddies and sometimes send them lurching across the countryside. This is where Fate sticks most closely to its roots, these cards shuffling back onto the top of the deck at regular intervals to establish hot spots of enemy activity. But at the same time, well, it’s one system among many, and everything around it is so built-up — so ornamented — that it’s hard to notice the tree for the forest.

The effect is noteworthy not only because it results in a very different sort of game, but because that game is shockingly well-told. Even when I was playing through Pandemic Legacy all those years ago, with its greater emphasis on narrative beats, I could not have predicted that Leacock would ever craft such an exemplar of ludic storytelling.

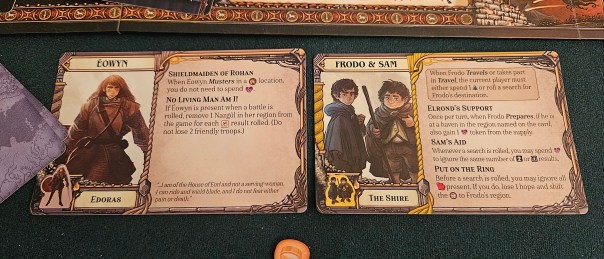

Take, for example, the way Fate of the Fellowship handles its characters. As in Pandemic, players command in-game avatars. These avatars travel between nodes, move and remove cubes, and accomplish objectives. Here, though, those nodes are distinct locales, those cubes are armies caught up in an existential battle, and those objectives are beats in a larger story.

And in all cases, it begins with the actual characters. Rather than serving as pawns with their own slight modification to some action or another, here they’re fleshed-out characters, each with their own strengths and frailties. When you glance at the map, you don’t see blue pawn, red pawn, yellow pawn. You see Legolas, whose bow is so sure that he can snipe orcs on the horizon. You see Boromir, the hero of Gondor who can capture an orcish nest, but who is so tempted by power that he can never share ring icons. You see Merry and Pippin, walking distractions for drawing attention away from their pal Frodo, but also comedic relief who can buoy their companions’ spirits with a song. You see Gollum, so sneaky as to make the perfect guide, but also so sneaky that no army will follow his command.

More than that, you always see at least two of these characters at a pop. It’s tempting to note that this marks a sea-change in how the game functions, allowing players to inhabit two spots at once and therefore swap cards with greater ease. But the more relevant takeaway is that this is a more character-oriented game than its predecessors. It feels like Lord of the Rings more than it feels like Pandemic, and it has everything to do with how one character can show up with an army to relieve someone else who has been pinned down by an army of ten thousand orcs. It’s the way Frodo can be spotted by Sauron’s roving eye, so Aragorn starts a row elsewhere to draw the big bunghole’s attention. It’s the mere fact that Gandalf can travel faster alone thanks to his cool horse.

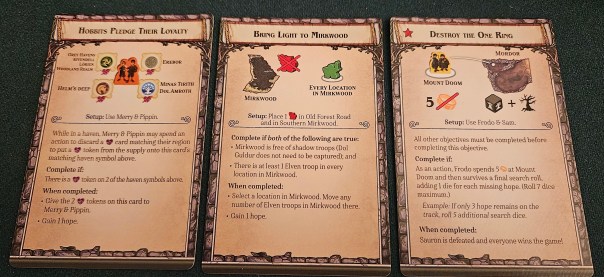

That sense of character permeates the rest of the design. Take, for example, the missions. Where Pandemic saw players gathering samples to produce vaccines, here you’re required to accomplish some number of objectives. But those objectives vary from session to session and always keep the characters in the spotlight. In one most recent playthrough, we needed Boromir to reclaim his honor, Arwen to unfurl the banner of Gondor, and Gandalf to confront the Balrog. But these aren’t as simple as moving a character to a destination. There are steps. Provisos. Punctuation marks. Where a lesser game would have us move Boromir to a space along the banks of the Anduin and call it good, Fate of the Fellowship offers drama. First, he needs to fight a battle where the last of his troops were lost! Then he sacrifices himself to wipe out of a bunch of orcs! And then, shortly after he’s removed from the game, his player receives a new character in replacement! Each beat of this story — the defeat, the comeback, even the brief pause between books — is the stuff of high drama. And the players are always in control. The game never cuts to a snippet of text, never intrudes with the proverbial cutscene. It just keeps going, its characters striving and failing and succeeding.

The big objective, the connective tissue between sessions, is that Frodo and Sam will always travel to Mount Doom to cast the One Ring into flame. This requires the halflings to creep across the map, sometimes sprinting across open country and other times lying low in various havens, before making their last-ditch foray into Mordor. Like everything else in Fate of the Fellowship, it’s dramatic. But even more impressively, the backdrop provided by the other missions allows it to feel fresh even though it gets repeated every play.

It’s no surprise, given the game’s pedigree and its source material, that there’s a ticking clock in the background. But, as with the characters and the missions, the clock is diegetic. There’s no point when Leacock looms over the table to say, hey guys, sorry, but it’s been eight rounds and that means you’ve lost. Instead, defeat is inevitable. Eventually so many orcs spill through the Black Gate that stemming the tide becomes impossible. Eventually the havens are corrupted and Frodo is discovered by Nazgûl. There’s no staving off a loss — unless someone manages to chuck some jewelry into a volcano.

As both a big nerd and a big softie, I can’t tell you how nice it is that Fate of the Fellowship understands its source material. More than understands — Leacock visibly loves this stuff, shows reverence for it, wants us to walk a mile in these hobbits’ trousers. The Shadow from Mordor isn’t an evil that can be defeated by force of arms — only delayed, only interrupted. In the end, this tale always comes back to common decency and endurance and friendship, the soldiers and heroes left somewhere back thataway, while hobbits wrestle to accomplish what spells and ghost armies cannot.

The dice tower, like many of the game’s bells and whistles, is not only unnecessary but subtractive.

It’s a shame the production doesn’t quite live up to the gusto of the telling. The board and characters are lovely, but the rest feels crafted to minimize overhead. There’s the chintzy dice tower, a cardboard-and-folds Barad-dûr, occupying just under half of the box’s real estate despite not being worth the cardboard it’s printed on. There are the paper-thin cards — paper paper, not the hefty cardstock we’re accustomed to — already warped in their shrink. There are the tiny armies, little more than the crumbs left behind by a toddler chowing down on Fruit Loops. Erū Ilúvatar forbid one ever tumble to the floor.

Even so, Fate of the Fellowship is something special. It’s already been a strong year for J.R.R. Tolkien adaptations thanks to Bryan Bornmueller’s Fellowship and Two Towers trick-taking games, with their chapter-by-chapter willingness to sweep the corners that usually go overlooked. Fate of the Fellowship goes the other way, compressing the trilogy into a surprisingly short playtime, but it never loses sight of what makes The Lord of the Rings such an enduring text.

It isn’t often that a board game puts itself across as a worthy inheritor of a grand tradition. There have been countless titles, both digital and analog, that explore Tolkien’s world, to greater or lesser effect, but too often, it must be said, to the lesser. This is one of the finest. It has been a long road from Pandemic, and the paths have grown so covered with leaves that it’s hard to make out its curve among the foothills. But this is still perhaps Matt Leacock’s best work, a wonderful tribute to one of the greatest works in the English canon.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, you can read my third-quarter update on all things Biff!)

Posted on December 1, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Fate of the Fellowship, Z-Man Games. Bookmark the permalink. 13 Comments.

There’s nothing better than when a game succeeds in weaving a story through its mechanisms. Reading your critique in tandem with Leacock’s design notes encourages me that Fate expertly captures the ‘show’ over ‘tell.’ What’s more, using his Pandemic system to encapsulate the hidden and creeping malice of Sauron’s will to create a tense coop – absent a malevolent human foil as in War of the Ring – hews closer to the source material.

After all, Tolkien’s message was not simply a fantastic play on the tired tropes of good against evil, but a very human story about despair and hope played out in the falls of Saruman, Boromir, Denethor, and Frodo juxtaposed against the endurance of Faramir, Aragorn, and Sam. What better game than Pandemic to capture the will to go on as the world crumbles around you?

Despite my love for Legacy, I’d given up on the idea of playing another Pandemic. Now I can’t wait to be inspired again.

“it’s hard to notice the tree for the forest.” — A reference to The Hobbit! I love Easter eggs like this.

So, I loathe LotR. I fell asleep when I tried to watch the movies (and when I woke up, I responded no when someone asked if I wanted to continue). I found the books dull, with so many pages where nothing happened and with two dimensional characters that seem nothing like human beings to me (aside Boromir, but he gets killed off early for being human; interesting message).

However, I have managed to enjoy LotR games in the past. I consider the Confrontation to be genius and regret selling it. I found the LCG to be serviceable (although Marvel Champions does what I want from these types of games better, so that’s the one I play). I had fun playing Knizia’s coöp LotR until I figured out the one simple trick that breaks the game.

Which brings me to my question. How essential is love of the story to enjoyment of the game? Is this one of the best LotR games out there? Or is this a game that someone can enjoy without sharing in the LotR love? reading your critique, the two seem intertwined.

I tend to default toward the “intertwined” reading of board games. As in, the setting always matters, or ought to. Plenty of players disagree with that stance.

In this case, though, I feel like somebody could appreciate the game even if they didn’t much care for Lord of the Rings. But that’s a hard call for me to make.

Hi Chearns,

Out of curiosity, do you remember what is the trick you found which breaks Knizia’s coop Lotr? I’ve played the game and read a lot about it but never heard of anything like that, and I’m always eager to learn more. Thanks!

Sure, we just spammed the main line and basically ignored all (or almost all, there might be some essential ones, its been over a decade) the side quest stuff. Once we started doing that, if I recall, we got to the boss with enough strength to win. This was without expansions, although, I don’t remember the first expansion really changing things up enough to counter that plan.

It’s the games I want the most that are always out of stock when I learn of them!

If you have one, maybe check your local game store! Mine had a dozen copies just sitting there.

My favourite thing is how Matt turned his puzzle game into a historical game. Something I definitely highlight when teaching the game as winning in these types of game is not necessarily the goal. At the same time I like how I can use Pandemic as a way of fore fronting a pretty complicated game. I have to admit that as a LOTR fan I was pretty skeptical of FotF. Also another reminder that I need to get War of the Ring to the table too. Thanks for the good write up Dan!

Thanks for reading, André!

I rated this a 4/10 but the reason might be interesting (or not). I think there’s an important difference in whether a game approaches its theme through details or systems.

For many gamers, getting the details more or less right is sufficient. Here’s a card that says “Eowyn” or “The Balrog”, the card does what we think Eowyn or the Balrog ought to do, and so, great, a thematic experience!

But this is actually fairly easy to achieve. Pick any game system: Risk, Chess, Parchesi, you name it. Having that system, it’s not terribly hard with a little imagination to envision what Merry or Gandalf or the sword Anduril would do within that system. And as a result, I find this kind of thing mostly unimpressive.

What’s harder is to find a /system/ that correctly models the theme. It’s the difference between, say, The Vote and Votes for Women. The latter is a details-design. Here’s a card that says “Senator Blah-Blah”, that Senator opposed the vote, so in this game he removes a cube from his state. That’s simple but it’s also superficial. Harder to correctly model the system by which the vote came about and why that was difficult.

And the problem with Fate is that the Pandemic model just does not work with the Lord of the Rings story. It just isn’t a fit. Pandemic is team whack-a-mole. That’s not how the LotR story works, at all. And consequently, you get a lot of story-absurd moments, which, it turns out — and this is the important part — /also beat against the details-design enthusiast/. For every “Gandalf kills the Balrog!” or “Boromir nobly sacrifices himself to save the day!”, you get all these moments that aren’t merely counterfactual, they’re preposterous, akin to Frodo dangling the ring in front of the Witch King in Jackson’s movie.

I had a game where Frodo and Sam waltzed into Mordor then sat on Mt. Doom for five turns until some other mission was complete so they could dunk the ring. Another where Eowyn marches an army to Isengard and then all the bad guys just walk out of Isengard and leave it ripe for the plucking. Another where the enemy makes a bee line for the Grey Havens and captures it in turn 3 or 4, ending the game.

It just doesn’t work, and it’s not because the designer didn’t fret about the details, it’s that he fretted so much about the details that he didn’t fret enough about the model. It doesn’t make sense for us as players to have conversations like “Ok, Eowyn, Legolas, and Frodo, let’s all arrange a meet-up in Ithilien so we can exchange these ‘Ithilien’ cards we’re all holding”. That might make sense in some settings but it isn’t how the LotR story works and thus it is a poor choice of a chassis on which to build a LotR game.

As a kid, I had SPI’s War of the Ring game. That was at first glance lovely, but it didn’t quite pull together as a game; for one thing, all the work put into the strategic military campaigns seemed to become just a side show to the progress of the Fellowship.

I’m not predisposed to like games without a human opponent; even as electronic computer technology has advanced by leaps and bounds, I’ve found that digital games gradually became less able to engage my sustained interest.

Fate of the Fellowship, however, looks like something that might well scratch my itch for a good treatment of The Lord of the Rings.

I’m catching on to the ability of the cooperative mode of game to facilitate interaction among people who don’t enjoy competitive negotiation. I’ve long been acquainted with that in the field of role-playing games, but Jenna Felli’s Shadows of Malice is so far my only experience in the higher-level (less zoomed in) board game context.

Pingback: Best Week 2025! Heart of Darkness! | SPACE-BIFF!