Nebulae, Medusae… Crownae?

Yesterday on BlueSky, Marceline Leiman asked a great question. Using only one or two extremely vague words, how would I describe the titles on offer at this year’s Indie Games Night Market?

Now that I’ve given it some thought, I think I have an answer, although perhaps it’s more concrete than she was looking for. More even than last year, these games seem like they’re pushing boundaries. They capture the spirit of what it means to be “indie.” Not only in the sense that they don’t have publishers. Rather, that they see the hobby from a perspective apart. They know board games; they love board games; they’re in conversation with board games. But more than that, they’re board games as lenses through which one might behold the entirety of the hobby. Its past. Its present. Its future.

How’s that for a wanky answer? Oh well. What follows are three games I love for different reasons, but perhaps love even better for the same reason — because they’re outsiders paying homage to their hobby, but doing so in a way that’s so defiantly indie.

Heavenly Bodies

High Tide will always have a special place in my heart. Designed by Marceline Leiman, it was the first Indie Games Night Market title I ever looked at. She reached out and asked if, hey, would I like to review her game, and maybe promote the market in the process? I’m so glad I did. Not long afterward, High Tide found a publisher. Not because of my review, to be clear. Because the game was that good. But that’s one of the reasons I write about these little things. Because while I know it can be frustrating to some readers to discover a game that might not be readily available, sometimes all they need is that extra push. After that review, other designers followed suit, reaching out to ask if, hey, would I like to review their games as well? It’s a tradition that will hopefully continue for years to come.

Heavenly Bodies is Leiman’s follow-up, a two-player card game that riffs on Gin Rummy but doesn’t feel quite like anything else out there. As in Gin Rummy, Heavenly Bodies is about building melds — sets consisting of three or four cards or runs of at least three cards. Simple. We’ve seen this a thousand times before.

Except there’s so much going on under the hood. For one thing, the deck composition isn’t what you might expect. There are four suits. That might sound suspiciously like an ordinary deck of playing cards. Then realize the suits are ranked. The planet suit consists of cards from 1 to 5. The moon, 6 to 9. Comet? 10 to 12. Finally, the star is limited to a single rank, 13.

Oh, and runs are limited to their suit. You’ll never build a run from 4 to 7, for instance, because it would mix planets and moons.

Meanwhile, the way cards are gained is one of Leiman’s biggest notes on Gin Rummy. As in that game, cards can be claimed either from the deck face-down or from the discard pile. Here, though, there are two discard piles. Worse — or better, depending on how they’ve filled out — drawing from a discard pile means taking all its cards at once. Some of them may be used to play melds, but the rest become negative points.

This transforms Heavenly Bodies into a selection of poison pills. Most turns consist of drawing two cards and then dumping one of them into a discard pile. If you have some inkling of what your opponent is holding, you can fill them with deadwood.

Scoring, too, pulls its own riffs. Earning points is anything but easy. You need melds, sure, but usually multiple melds of the same suit before you’ll see even a single point. Even then, you’re encouraged to build beefier melds with additional cards, pushing you to dip into those poisoned wells. Even a winning combo offers a choice between pushing further for extra game points — but maybe giving their rival enough wiggle room to catch up — or ending the hand right then and there. The whole thing feels simultaneously snuggly and scratchy, like a familiar blanket but with the occasional LEGO hidden under the covers.

I will say, I’m not sure the numbers have been tuned correctly. The star suit is the prime offender here, a little too potent, a little too capable of ending a hand out of nowhere. And the game seems to reward holdouts more than early adopters, resulting in both players holding huge hands of cards rather than wagering bit by bit into the game state. I wouldn’t have minded seeing some reward for melding early.

But, look, I might be talking outta my black hole. Even when I’m getting walloped, Heavenly Bodies feels so good to handle that it’s hard not to keep coming back. It’s a quieter reinvention than High Tide, not as flashy as that game’s hand-stamped wooden hexes. But it has a silken quality that makes it pleasant on the fingertips all the same.

Medusa’s Garden

The problem I have with too many social deduction games is how they tend to produce static states: everyone frozen in time, the conundrum less social than logical, like looking around a table and seeing clockwork components rather than people.

Through that lens, it’s hard not to regard Medusa’s Garden, designed by Phil Gross and Jono Naito-Tetro, as the most literal possible expression of how social deduction reduces people to statues.

“Through that lens.” Look at me. I’m a riot. Medusa’s Garden, you see, is played through a lens. Specifically a hand mirror, too small to observe more than a few details at a time, but big enough to cause a monster to perspire. The players, meanwhile, are statues. All apart from one of them who happens to be the most famous of gorgons herself.

Picture this. A garden of frozen victims, suspended in their final state of terror. One of them is Medusa. When she brushes against a statue, it gradually crumbles. The process takes about ten seconds, counted silently, at which point the brushed player must shatter, either collapsing in place or stepping away from the garden. The player with the mirror is Perseus, searching for the gorgon through reflection alone. If he can name the identity of Medusa before half of the garden has been shattered, he wins. Otherwise, she wins.

That’s all there is to it. There doesn’t need to be more. Unlike the top-heavy scripts of something like Blood on the Clocktower — an amazing game, to be clear! — Medusa’s Garden doesn’t bother with roles. Players are allowed to take a cue from their statue card if they don’t have an idea for how they’d like to pose, but otherwise there isn’t, say, a hoplite statue or a maiden statue or a slave boy statue. In rictus, all have been rendered identical.

I’m sure there will be those who argue that Medusa’s Garden is light on decisions. True enough, this isn’t the most cerebral game. It’s a mix of street theater, living statuary, and two minutes as a prop in somebody else’s duel. Perseus and Medusa are the leading lights here, the former slowly orbiting the garden while the latter furtively shatters her trophies and hopes to escape with her head attached.

But, again, it takes one minute to learn and another two minutes to play, and, crucially, involves the entire cast equally. There’s none of the pressure that usually attends social deduction. There are no stammered questions, no awkward lies, none of those moments where the guy who’s played the game five hundred times unleashes a Benoit Blanc rush of exposition.” Susan claimed she was the nun, which means her neighbor would have to be the rook, but Davide made eye contact with Jim, which makes it obvious that Dwayne is the werewolf!” As someone who’s frozen up on more than one occasion, it’s refreshing to play a game where the sum expectation is that I must freeze up.

It’s pure. That’s what I think I’m saying. It’s the perfect way to put some rubber in your joints after sitting through a four-hour convention game. Social deduction games often excel as icebreakers. Medusa’s Garden pulls double duty in that respect. It gets everyone laughing and qualifies as some light calisthenics as a bonus. You don’t even need to mention the ways it’s conversant with the format’s niggling problems. That is, unless you’re hoping to suss out which members of the garden are big damn nerds like yourself.

Crownfell

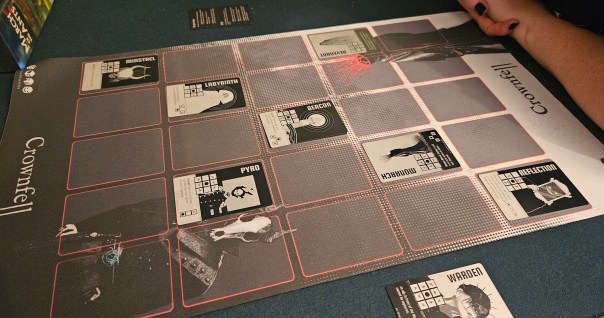

Speaking of games that are in conversation with other games, we come at last to Crownfell, Mike Berg’s handsome take on The Duke, Chess, and countless forebears that have been lost to time.

Played with only a handful of troops at a time, Crownfell feels a bit like the version of Chess we sometimes played as kids, where the goal was less about cornering your opponent’s king than about murdering every single opposing piece on the board. That board is compact, only five-by-five spaces, downright claustrophobic next to some of its kin. Those pieces, meanwhile, are function incarnate. Berg translates the visual language of The Duke more or less verbatim, a smart move given that game’s legibility. Any unit’s possible moves can be spotted at a glance thanks to the handy rubric in the middle of each card.

But in Berg’s own twist on the format, these units are madcap. There’s the Martyr, which can be removed from the board to flip an enemy card to your color. That would be overpowered in any other game. In Crownfell, where it fraternizes with the Labyrinth (locks neighboring enemy units), the Stag (deploys cards to additional spaces), and the Revenant (parks atop another card to lock it in place forever), the Martyr is one game-breaking beast among many.

The real danger with games like this is that they tend to spin their wheels without going anywhere. In design circles, we sometimes use the term “degeneration” to describe games that decay away from their intended states. But with quite a few Chess-inspired games, the risk is that these games won’t degenerate. Players measure out every possible move, stick to safe spots, and avoid risks. It’s like high-level Chess without a timer.

Berg’s answer to this conundrum is a bold one, in part because it risks immunity to that same degeneration. The center space is the crown. Whenever a unit steps onto it, they’re allowed to rally. This affords them a choice between a free move, another deployment, or — and this is the biggie — a retrieved unit from the discard pile, no matter who originally owned it. Units are reduced to little mercenaries, switching sides with abandon. It isn’t quite as determinate as the side-swapping pieces of Onitama, more up to player action than hard-coded into each move, but a paternity test would show a few telling strands.

Which could pose problems of its own! In theory, very little prevents players from swapping units ad infinitum, both armies hovering around five units for some indeterminate duration. Indeed, the game’s original rules, which Berg kindly shared with me some months past, made such a state likely thanks to a tic of geography that has since been done away with.

Nowadays the practice is much different. That central crown space encourages risk, drawing both players onto the board, without offering such a bounty of opportunity that both sides remain fully staffed. Crownfell is still an unexpected sort of game. At once, it’s deterministic and full of surprises. It asks players to parcel out their moves, creating interlocking blocks of armor and spears of threat. But it also asks them to go a little mad sometimes — to light up a distant troop with the Pyro or radically reposition with the Stag or Minstrel.

The result is a wonderful little game, one that feels much larger than its 18 cards. It helps that Strega Wolf van den Berg’s illustrations are obsidian-sharp. There’s nothing quite like some black-on-black warriors speckled with blood. All the better when their behavior on the battlefield matches their spiked armor.

(In addition to being available this weekend, Crownfell is on preorder at The Game Crafter.)

Whew. Sorry for the big batch review. With the Indie Games Night Market barreling toward us, there was no other way to discuss everything in time. And there are still some excellent titles I haven’t had enough time with to discuss in depth. I’ll be covering those in the coming weeks. For now, games like these are a testament to the sheer creativity and audacity on display in this hobby’s independent wing. I care about your indie game. Titles like these demonstrate why.

Complimentary copies of Heavenly Bodies, Medusa’s Garden, and Crownfell were provided by their respective designers.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, you can read my third-quarter update on all things Biff!)

Posted on November 18, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Crownfell, Heavenly Bodies, Indie Games Night Market, Medusa's Garden, Roly Poly Games, We Heart Games. Bookmark the permalink. 9 Comments.

Tom Vasel are you listening? Nice one Dan 🙂

Haha, I’m the worst.

As someone who will be attending the Indie Games Night Market this weekend–any other standout games that you won’t have a chance to write about until later but that you would recommend taking a look at? I’d hate to find out later that there was a hidden gem I missed out on!

A few more are still en route, but the two I have in-hand are This Is Not a Game About a Pipe and Conviction, both of which are very interesting indeed. Be warned, though, that I haven’t played either of them enough to provide a strong recommendation.

Like many others I can’t attend Pax U, so after last year’s coverage it was nice to see Marcie’s game and Torchlit get picked up by publishers. If you had to guess, will any of these games be available after the show?

I don’t have any insider information. But if I had to guess?

Crownfell is up for preorder, as noted in the review.

Medusa’s Garden is associated with DVC Games, which means it probably has a good shot of continued life. Although it’s also one of the easiest to kitbash yourself.

The paper games I covered on Monday are all fairly easy to print, so their designers could either continue printing them or provide files if they were so inclined.

Chasing Shadows is by the same designer as Torchlit, so I imagine he has an inside track to a small print run after the convention.

Rowing is pretty easy to reproduce…

Actually, a lot of these could be reasonably recreated outside of the indie market context. The main barriers being sales and shipping and so forth.

Thanks Dan!

Pingback: Crownfell Design Diary: No such thing as a bad idea - We Heart Games

Pingback: Best Week 2025! Beatrixmania! | SPACE-BIFF!