Calimala Olives

Sometimes I assume that everybody around me knows the same things that I know. To wit: when I began teaching the second edition of Calimala — the first edition of which was published in 2017 and launched Fabio Lopiano’s career as a game designer — everyone at the table started talking about Kalamata olives, and not, you know, the Arte di Calimala, the cloth finishers guild that was the economic backbone of Florence for two centuries.

Why would I assume that everybody knows about the Arte di Calimala? Don’t ask me. I’m in the assumptions business, not the understanding my assumptions business. At any rate, Calimala isn’t a game that requires much historical knowledge. Sure, Lopiano includes a number of nods to Florentine business practices and even city governance, but it’s too razor-toothed to matter. This one is sharp. But it may, perhaps, contain the seeds that would lead Lopiano to clutter his later designs with interlocking systems.

Welcome to Florence. Italy in the thirteenth century was a dangerous spot to hang your hat, which made the secretive practices of the Arte di Calimala all the more crucial to Florence’s success. Their wool was imported, mostly from Northern France — England’s ample bales were the domain of a sister guild and competitor, the Arte della Lana — and then dyed, fulled, calendared, and finished, at which point the cloth could be exported across Europe.

As a participant house in this trade, players in Calimala are thrust into a truly competitive scene, one that’s unusually cutthroat for a modern Eurogame. Even coming to Calimala late, after playing Merv, Sankoré, and Shackleton Base, the central action-selection system is familiar, asking players to navigate intersecting interests that may well benefit their opposition.

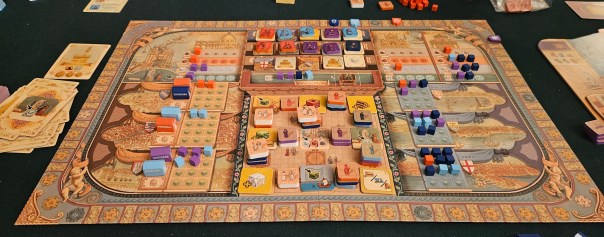

Unlike some of those later titles, the gist is refreshingly unburdened by snaggy rules or multiple phases. The board’s central arena is a grid of nine actions representing the wool market itself. On a turn, players deploy a worker — either a family member or an outside contractor — to the market, at which point they take the two actions that border their chosen space. Bringing home resources, constructing workshops or trade vessels, or perhaps donating to the local churches are all the domain of these cloth magnates.

Like anybody making a living in a city based on competition, though, these activities are unusually fraught. Rather than simply placing your worker and being done with it, these laborers are stacked one atop the other. Thus, if you place a worker on the space between gathering wood and exporting cloth overland, you’ll take those two actions, but then the workers stacked beneath your own also receive the opportunity to do the same. Actions in Calimala have a way of compounding. This presents an opportunity for canny players. I’ve never set up a stall in a marketplace before, but it feels like something a wool merchant would do, staking out the locales that will draw the greatest traffic and heftiest purses. At the same time, there’s some bite to the whole enterprise. When somebody is in the lead, plopping your worker atop theirs only furthers their success.

There are other particulars to consider. Whenever a worker is presented with an “impossible” action, including those that wouldn’t be impossible if only they resolved things in a slightly different order, they’re allowed to draw an action card. These furnish free actions on later turns. Which, again, can result in a spree of free actions if players aren’t careful with their placements. More than once, I’ve watched somebody draw two, three, even four of these cards, to groans from everybody at the table. Calimala is, above all, a social game, a sharp departure from the heads-down tendencies of so many modern Eurogames.

And then there’s the council in the Palazzo Vecchio. Florence was structured around a council of nine men, the signoria, drawn by lot and sequestered in the palace tower for the duration of their service. In theory, this prevented the tiny republic from being corrupted by would-be nobles. In practice… well, the Medici eventually gamed the system to their benefit, which is exactly what players are tasked with doing. Whenever one of those worker stacks in the market gets too deep, the bottommost representative gets called up into the tower.

Meet Calimala’s scoring system. It’s infuriating. Sometimes in a good way. But also in the regular infuriating way. Arranged across the Palazzo Vecchio are fifteen scoring tiles, one for pretty much everything your house might show an interest in. Donating to churches, commissioning statues, exporting to cities both by land and by sea… everything.

The way it works is simple. When a worker enters the tower, they trigger the next scoring category. This is a small enough bump, only three points for that category’s leader, down to a measly one point for whichever house sits in third place. But having a representative in the tower turns out to be a very good thing indeed. Ties in Calamala are common. So common that there’s a multi-step rubric for resolving any potential draw. And the main way to resolve such an occurrence is by consulting the councilors in the tower.

So much for incorruptible.

This is the beauty of Calimala, by the way. Everything about this game is sinister. Every placement is loaded, potentially benefiting your rivals, setting up a series of cascading actions later, or maybe parking yourself in some out-of-the-way corner of the market where nobody will ever see your booth of convention kitsch. (Too close to home?) Meanwhile, seating your household’s representatives in the tower is such a boon that it encourages players to… not work together, exactly. But to develop those mutual relationships that appear parasitic to outsiders.

In those same ways, Calimala runs against the grain. While its social aspects, especially in its action-selection grid, reflect Lopiano’s later work, it’s the least cluttered of his designs by a mile. Players are set at wrestling with one another, not so much with the system. This is a boon, on the whole, but its friction also chafes. To the modern Eurogame player, of which I am one whether I like it or not, this can feel direct and abrasive, sans the mechanical cladding for insulating us from our worst mistakes. It’s no wonder that Lopiano’s later titles have piled on additional levers and gears.

Personally, I find I prefer his designs that fall somewhere in the middle. Merv and Shackleton Base are still social games at their core, many of their actions impacting one’s rivals both to their benefit and disadvantage, while going a little further in evoking their sense of place. And, sure, they’re both a little more interesting to me as objects of repeat play.

But Calimala stands out, not only as a museum piece to witness where Lopiano began his design journey, but as a deeper investigation of the social headspace his designs engender. So this is what interests the man, these interlocking actions and their long-term import. Those same fingerprints are all over his later creations. Here, though, they’re at their most evident, the entirety of Calimala structured around a set of entangled incentives and disincentives. As in Merv, as in Sankoré, even as in Autobahn, here is a designer who wants to use these locales as drapery, but also as settings in their own right, calling to mind the bustle of the marketplace, the unfairness of the tower, the precariousness of the city-state republic.

And, in both cases, Lopiano uses these systems and settings alike to draw his players out of their shell, to encourage them to think about the other faces seated round the table. His later designs may have done it more subtly, but it’s wonderful to see those faces laid bare here. Calimala is many things. An early effort, in some ways raw and unrefined, especially where those free actions are concerned. But also elegant, already calendared and spun into the threads that will become the fabric of his later work.

At the very least, maybe now some folks won’t think the Calimala is an olive.

A complimentary copy of Calimala was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my second-quarter update!)

Posted on August 21, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Alley Cat Games, Board Games, Calimala. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

Quite interesting, thanks. I wonder if you’ve ever tried Ragusa, from Lopiano?

Sadly, that’s one of the gaps in my Lopiano knowledge.

I love that you describe something published in 2017 as a museum piece! They grow up so fast haha.

Thanks for the review, another great read!

My life exists in only two segments: pre-‘rona, post-‘rona. 2017 might as well be 1999!

I had not noticed that they are by the same author; Ragusa seems to have flown more under the radar of publicity.

As in Calimala and Merv, actions for one player cascade into actions for others. With buildings placed at nodes adjacent to three hexagons, it’s a bit like Catan (but with players rather than dice deciding which get activated).

It’s also unusual in how raw resources are treated basically as continuous streams of supply (rather like tracing supply in a lot of wargames).

The limit on how many buildings you can have applies based on your resource network after you build the new one. (Then a “maintenance overhead” is by the same means automatically deducted from the supply for building, as opposed to accounting with fluctuating piles of cubes or whatever.)

Perhaps even more than in Calimala, there’s a degree of elegance at odds with the fashion for increasingly baroque machinery in games.

I just recently discovered Calimala (2nd edition printing) deluxe edition at a convention where a friend of mine introduced us to it. I immediately liked this game. The interaction, vying for position, always watching the board and your opponent’s moves – this has recently become my preferred type of game as opposed to strict euros which are more on the multiplayer solitaire side. Dan, you said this is a stripped down version of his later works. Boy, I like it this way. I can’t imagine adding more. Seems like it would just introduce unnecessary complexity and detract from the main event which is to watch your opponents and respond to their moves. I ended up buying a copy. Ally Cat games just released the 2nd edition (with a deluxe option) and I highly recommend it for people who would like a more interactive break from standard euros.

I think the interaction among players’ moves — bringing more emergent complexity from a relatively simple rules set — that is more typical of the older German school facilitates quicker completion. It’s pretty great to finish a 5-player game in an hour, versus half again or twice as long for a 4-player game.

Simply providing a good 5-sided game in the first place is remarkable these days, and important in the contexts in which I’m likely to get in a game. (Having a couple play a side as a team is usually less than ideal.)

I think it tends to be easier for most people to avoid “analysis paralysis” regarding the uncertainties that other people bring to the table than to avoid getting mired in trying to solve a puzzle of rules complications. As with dice or cards, the practical limitations are more obvious.

(The shift from the former to the latter kind of complexity in multi-sided games helps to avoid degenerate strategies that are not such a problem in a two-sided context. Ability more carefully to target interactions can also help avoid the side effects giving rise to those, but the ‘Euro’ school deprecates the “take that” aspect.)

Pingback: Sun Besties! | SPACE-BIFF!