Most Select of Board Games

The temple complex of Ipet-isut, “the most select of places,” today known as Karnak, is unique among Egyptian sites for the sheer duration of its construction. Nearly thirty pharaohs, from the Middle Kingdom to the Greek Ptolemies, added to the complex’s collection of statues, arches, obelisks, columns, hieroglyphs… pretty much anything we associate with “very old building.”

Now Karnak has one more addition: a board game by design collective Jasper Beatrix. Yep, the same folks whose designs I’ve been admiring all year. And like Karnak itself, this one necessitates some excavation.

Here’s a theoretical situation for you. Let’s say you’re an architect in the Middle Kingdom. The Pharaoh comes along and says, “Hey bud, I want you to make something that will stand as a testament to my greatness for all of time. Something that really says, This guy was the tops, you know? Therefore, I command you to create an edifice with three triangles in it.”

Nice! You can do that. It takes some time, but you finally finish a structure with three triangles. The Pharaoh nods approvingly.

But then the Pharaoh dies. His successor, a real dingbat, comes along and says, “You know, that structure with three triangles is nice and all, but you know what would really pop? Statues. But not just any statues. Statues on top of calendar disks. At least two of them.”

You aren’t in love with statues. But it’s good to have guaranteed employment, so you build the statues stone by stone. The Pharaoh nods approvingly.

But there’s a problem. No sooner have you completed the Pharaoh’s statues than one of your competitors begins adding to them. They build a big goofy wall right into the side of one of the statues. It runs down the slope and into the Nile. Meanwhile, they perch a massive block atop the other statue’s head. “Now wait a minute!” you cry. “That won’t stand the test of time! It will topple within the century for certain!”

Your competitor shrugs. “The Pharaoh said he wanted me to build the tallest structure in the land. Now I’ve done that. Oh, and he wanted a structure that touched the waters of the Nile and one of the holy sites, even though everyone knows the holy sites are too far inland for that. But now I’ve bridged your statue to the Nile. The Pharaoh loves it.”

A week later, the Pharaoh dies of some mysterious disease. His successor, a literal child, commands that two identical structures be constructed in proximity to the Nile. By now, though, the only thing touching the Nile is a wall that runs all the way to your statue. Okay, maybe you can repurpose some of those blocks to make something new.

Except now a priest appears. “This is all sacred ground,” the priest says, and declares the merger of your beautiful statue and your competitor’s ugly wall to be the Middle Kingdom equivalent of a UNESCO heritage site. “Nothing may be added to nor removed from this beautiful edifice,” the priest announces.

Just like that, your greatest legacy becomes an unholy abomination that stands for three thousand years.

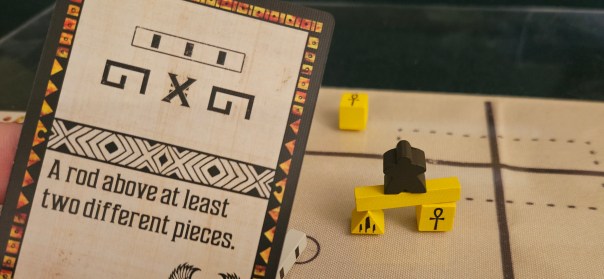

This is Karnak in a nutshell. Players earn points from completing designs. But because the mat and its components are shared by all, there’s little to prevent somebody from adding to an existing structure, repurposing its stones for another temple elsewhere, or spanning a gap to create a ramshackle mess that still pleases the whims of a god-king. The rules are simple, with turns coming down to adding a couple of pieces to the map, moving a piece, or drawing new designs, but the game’s social space — the tension it engenders between players — is as tangled as the thicket of obelisks and statues that sprout in your wake.

It also lacks some of the immediacy of other DVC titles. To be sure, the company’s catalog is packed with oddballs, with instructions that don’t always communicate what precisely players will be doing. Reading the rules for Signal, Corvids, Typeset, and Scream Park, I struggled to envision the shape of the game. Nowhere was that more apparent than in Here Lies. You mean we’re telling a story? I’m supposed to invent information that isn’t necessarily provided by the game? Wait, what exactly are we doing here?

But within a few minutes of starting those games, their appeal becomes obvious. These are clever, even subversive titles, tinkering not only with their tabletop genres, but in some cases with their meta-fiction. Here Lies, for instance, riffs on the tropes and expectations of the mystery yarn more than any other board game by allowing players to be inventive. Much like reading a Sherlock Homes or Encyclopedia Brown story, Here Lies rewards thinking outside the box — a tremendous feat for a game that comes in a package that’s smaller than an actual shoebox.

Karnak is similar in the sense that it doesn’t immediately communicate its appeal. But that gap extends beyond the rulebook. It takes a play or two before these blocks settle into place. Even then, it’s more group-dependent than its peers. The exact same question — say, whether two pieces are truly “touching,” what happens when a slight jostle sends a structure’s capstone toppling to the mat, or how to work around the slight (but oh so significant!) creases in the mat’s fabric — can have completely different answers depending on the composition and disposition of the people gathered around the table. Making this even trickier to navigate, this is a competitive game. Signal and Here Lies both had their gray spaces, but their cooperative nature made such clashes easy to resolve. Here, any given ruling may well favor one player over another. In a game this catty, those ambiguities are liable to leave a bad taste in the mouth.

But it does click, after a while, and possibly after some broad interpretations of the rules’ intentions. When it does, Karnak is every bit as subversive as its peers, and definitely in the same ballpark cleverness-wise, if perhaps not quite as evergreen.

What makes Karnak so devious is its willingness to let players mess with each other. Your structure becomes my structure. Or worse, I scavenge your structure for extra bricks. The game is freewheeling in the extreme. If something on the mat hasn’t been pinned down, anybody can repurpose it to their own ends. Making this even more fraught, it’s necessary to periodically reveal one’s designs, earning bonus cards and freeing up space for additional designs in your hand, but nothing scores until the game actually concludes. If my structures have been dismantled or reimagined in the meantime, it’s entirely possible that they won’t score. There’s real potential for — this is the technical term — dickishness. If you see that one structure is fulfilling two of my designs, go ahead and tear them down. Even better, merge them into some towering mess that fulfills one of your designs while antiquating two of mine. Karnak rewards those who pay attention. It also rewards those who are willing to be very mean indeed.

This isn’t to say that anything can be undone. There are ways to freeze structures. Blocks, when replaced, swap from yellow to white, indicating that they’re no longer moveable. Blocks underneath others are similarly untouchable, making it possible to heap some extra statues atop your temple so that rivals will at least have to shift something before they’re allowed to displace the crucial interior.

And then there are priests.

These guys are jerks. AND IN THE GAME. As a free action, you can deploy one of these god-botherers to any structure. That structure is then frozen. Nothing can be added to it. Nothing can be removed. It remains frozen in time. At least until scoring. Sweeping the pieces into their baggies represents a degree of inevitability that’s beyond even Jasper Beatrix’s scope.

What’s wrong with that? you might be asking. Isn’t it a good thing to freeze your structures? Sure. But you aren’t considering the offensive possibilities. Priests make it possible to flip an opposing structure to your side and then lock it. Or maybe even remove a load-bearing (points-wise, not structurally) block from a rival’s arch, killing multiple of their design cards, and then freezing the now-worthless heap.

That’s the sort of inventiveness Jasper Beatrix games thrive on. These dynamics are wholly social. The rules don’t spell it out for you. To some degree, neither does the gameplay. Oh no. Karnak only springs to life when you assemble some goblins, let them tinker for a couple sessions, and then watch as they find ever-nastier ways to undermine each other.

Which is to say, Karnak is a game that can be played shrewdly, with players who angle for advantage at every turn, even when it doesn’t seem like it at first glance. Like the real-world Karnak, it needs room and time to breathe. Hopefully not more than a century or three.

That puts it on interesting footing. Karnak isn’t as immediately gripping as some of its peers, but a slightly less-gripping Jasper Beatrix game is still better than ninety percent of games out there. On the whole, this is another success for DVC Games, albeit a more contingent success. I recommend getting rid of the pleats — I employed the same plexiglass that I use for pinning paper wargaming maps to the table — but there’s an argument to be made that the folds add some texture to work around. Personally, we got tired of replacing pieces that had toppled over.

At its best, though, this is a solid entry in an already admirable catalog. With the right group, it captures the intense rivalries of court architects who must vie for a divine brat’s approval. Hopefully future archaeologists won’t assume it says too much about our current predicament.

A complimentary copy of Karnak was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my second-quarter update!)

Posted on July 29, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, DVC Games, Karnak. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

On the strength of your recommendations I bought Signals, Here Lies, Scream Park, and Typeset and proceeded to immediately fall in love with them. They’re so weird and creative in such small boxes (reminds me of the early days of oink albeit with less of an eye to mainstream appeal).I really hope you continue to cover them because while Karnak doesn’t seem to be for me, their upcoming lineup all looks cool. Pacts (two player I split you choose area control) Playthings (a game of hiding stuff and setting traps with the illustrator from Scream Park) and Inkwell (Azul style set collection and drafting but themed around real illuminated manuscripts).

What would you say unites their design style? They seem to love games with freestyle spacial placement but beyond that I have trouble parsing exactly what unites them, if anything.

Definitely! I intend to keep covering DVC’s stuff for as long as they’ll have me. I’m especially interested in Inkwell — anything with illuminated manuscripts is my jam.

Hm, I think there are a few factors that unify their design ethos. They want small games with compact rules and a short playtime that emphasize a particular social feeling. High interaction, but not too punitive. An emphasis on cleverness over the usual combo-building. Celebrations of creativity. Since they’re a small publisher, they probably also prioritize simple components that don’t cost too much.

But that’s just my guess! If anything, I’m happy to keep exploring their stuff because it’s so unexpected.

Could you please share your top 2 of these games? =)

I want to buy everything DVC offers, they seem like a revelation. Unfortunately that would nearly double my game collection that I’ve kept carefully limited over the years (refusing to become one of those people who buys more games than they play, and mostly only plays anything once). These games feel like they came out of nowhere, finding room for creativity that was just out of sight of the industry, around corners nobody noticed, and the treasure they’ve unearthed/crafted is seemingly specifically to my tastes.

I’ve settled for now to appreciate Signal, and meanwhile evangelize the other games to my friends. The couple who loves Halloween and throws an elaborate party every year (with repurposed decorations!) got to hear about Scream Park, of course.

Hey, that’s a great policy! Good restraint! I hope you get to try DVC’s other titles at some point, even if you can’t personally add them to your collection.

Oh! Plexiglass to flatten wargame maps. That sounds brilliant, I’ll have to try that

Pingback: Cutting the Cottage Pie | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2025! Beatrixmania! | SPACE-BIFF!