I’ll Rest When I’m Blinked Out of Existence

The gods have betrayed us. At the tolling of a distant bell, the world they once safeguarded now sloughs like burned skin. As even the stars lid their brilliance one by one, we enact one final act of defiance, setting out into the wasteland break ourselves against them. We will perish. The only remaining question is how.

That’s the premise behind The Restless, Winslow Dumaine’s forthcoming… well, look, this thing defies easy description. Is The Restless an adventure game? A dice-chucker? A phallus-filled nightmare?

Yes. All those and more. When I teasingly recommended it to three victims as a chill game about unexpected friendships, I wasn’t even lying. It’s just that Dumaine’s hand-drawn illustrations have such the consistency of chilled intestinal jelly that it’s easy to miss the buddy tale for all the guts. This one is hairy, abrasive, and, against all odds, meditative. Among the dismembered torsos and countless rolls of a d20, there is a monkey’s yawp that hovers between defiance and acceptance. We are all corpses in waiting. But maybe, just maybe, that’s all right.

It begins, as all calls to adventure must, with a party.

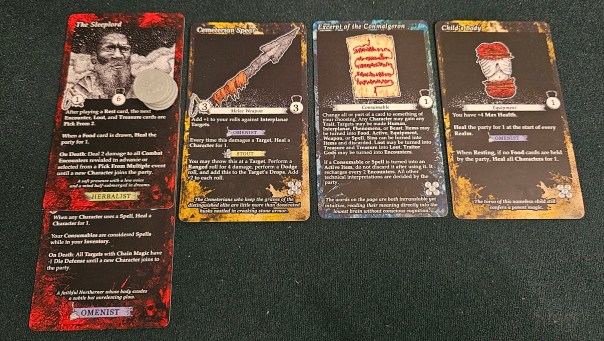

Yet these are no adventurers. Describing your band as “ragged” would be to pay them an undeserved compliment. These are skeins of bristled thread left over from the burning, brittle wedges of skin torn bleeding from a cracked lip. Not only have they been broken on the wheel; their shapes hardly match. There is a daughter, given no description beyond her daughterhood, dressed in rags and capable of finishing off any foe that is already moments from death. Another is a resurrected sinner, his only penitent fiber a petrified arm. One, the most beautifully adorned and skilled of the group, peers through dead eyes. In all of my plays, I’ve somehow drawn a beggar with camp-thin limbs, his bones more pronounced than his musculature.

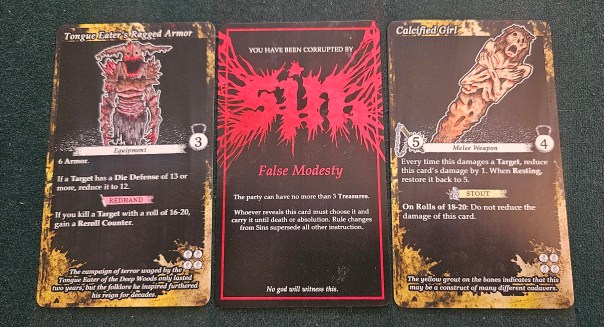

There are twenty in all, although only four will begin the journey. Because this is a game, they are granted a few essential digits: a weak unarmed attack, a weight limit, a maximum pool of health. But it’s hard to miss the other details. Such as their character classes. There are no paladins or wizards among them, only the like of Redhands, Omenists, and Silvertongues. Hard to miss, too, that each and every wanderer has two abilities. One is customary fare, some bonus to healing or attack. The other only triggers upon their early demise.

Because these are not adventurers. They are the condemned.

It’s tempting to invoke the usual antecedents. There should be an adage akin to Godwin’s Law that the internet will inevitably compare anything with bleak and ambiguously symbolic imagery to Dark Souls. This is a gray and red world, all ash and arterial blood, with tactical splashes of color that only accentuate the gloom.

If anything, though, the comparison sells The Restless short. Every image in the game, all 700+ cards, are closer to the metal inspirations of something out of Nate Hayden’s curdled dreams, Cave Evil or Warcults or Psycho Raiders. But every so often, two or three times per game, something would strike me upside the skull like a vision out of Cormac McCarthy. I have a cast-iron stomach for most things corporeal, but the occasional scene sent my stomach doing loops. One in particular — grimly entitled “Forced Birth,” to give you a sense for what’s to come — was dire enough that my group was overjoyed when we were given the option of facing a different encounter instead.

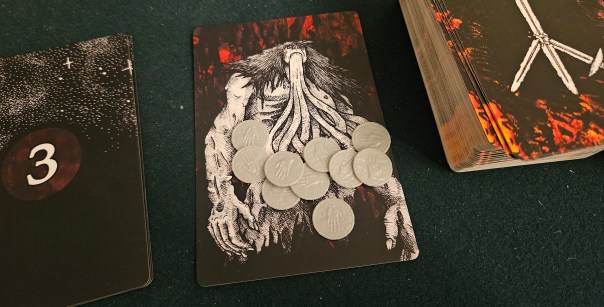

For all that, The Restless plays its actual adventuring surprisingly straight. The overarching structure presents itself in daunting fashion: you must pass through five blighted realms, each consisting of four encounters, before facing the traitor god. For the most part, this consists of flipping a card to see what happens. Most of the time, your crew will fall headlong into a combat encounter. These demand copious rolls and exchanged wounds; there’s nothing noteworthy or innovative to the combat itself, so I’ll decline to bore you with a description of how hits are tallied. The rest of the time, either you receive a run-of-the-mill text encounter (roll to determine whether you heal or gain an item, that sort of thing) or else you happen across a merchant. These latter options are the most involved. Provided you can pay the merchant’s toll, you’re offered a selection of items. There’s no currency, strictly speaking, although you can make change with reroll counters.

Put another way, it isn’t exactly as mind-melting as its premise might have you believe. There are none of the choose-your-own-adventure sensibilities of Greg Favro’s Spire’s End, nor is it as cruel and abrupt as Peer Sylvester’s The Lost Expedition. Terrible things will befall your characters, and you’ll witness corruptions that any decent person would prefer to rub out of their memory, but you bear a decent chance of reaching the traitor god. With some luck and a few good item selections, you may even kill the bastard.

And yet The Restless is a tremendous experience. A slippery experience, slick with blood and cut through with more than one design gap, but worthwhile all the same.

It comes down to a combination of factors, none of which can be divided from the others. As a game, it’s defiantly straightforward — until the moment it isn’t. Combat, as I noted, is straightforward. You whack at your target. If you miss, they whack you back. On the off-chance you have a ranged weapon, you take a potshot and then make a dodge roll.

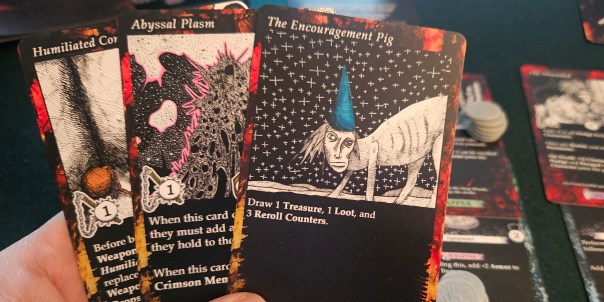

Interspersed throughout are little considerations that give these sequences some teeth. Enemies, items, and your characters all put their own spin on the proceedings. That’s to be expected; what’s surprising, however, is just how much each enemy, item, and character stands out from the others. A broken sword might get lodged into a monster’s flesh. A spear can be thrust or thrown, and in the latter case might be lost until the fight’s conclusion. Other tools — an oversized femur, a sword with its previous owner’s hand still clutched about the hilt, a flail whose business end is made from repurposed statuary — are all distinct in their own right. Choosing the right tool for the job, what to carry and what to sell and what to discard, requires unanticipated care.

That’s only the weapons. There’s also armor, which can absorb damage but not obviate it entirely, and disturbing trinkets for modifying the rules, and spells with limited charges, alongside consumables like dog meat for topping off your waning pool of health. Notably, pretty much every item grows more powerful when paired with the right class of adventurer. Despite overflowing with cards, nearly everything feels distinct and worthy of consideration.

Dumaine’s cards are endowed with blacker arts as well, little tricks that upend the usual procedures. One example is found in the treasure deck. Periodically, your crew will draw a sin. These are sticky buggers, latching themselves onto whomever drew them and, worse, altering the rules in your disfavor. In our most recent session, the sin of false modesty prevented our entire party from holding more than three treasures. Just like that, our arsenal of weapons, armor, and trinkets was pruned to a curated selection of three damage-dealers. Sins can be absolved, although as in certain soteriologies this can be more theoretical than practical. That particular session concluded with our party ridden with so many sins that we could hardly get in a prayer.

Meanwhile, every realm also offers its own twist. Once, we were told to arrange encounter cards in a grid and pick a path through them. Another realm made it impossible to heal; when we leaped at the opportunity to travel somewhere else, our new destination forced our reroll counters to grow barbs, inflicting damage whenever we used them.

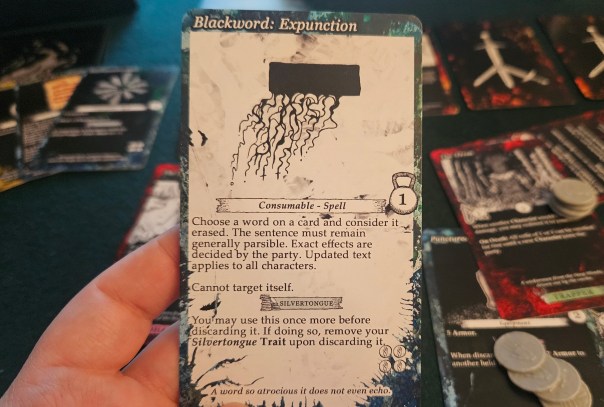

Indeed, the reroll counters themselves add some necessary structure to The Restless. The entire thing, clocking in at maybe two hours, is arranged like a press-your-luck game, its pathways lined with beckoning temptations. Want to peel through more of the treasure deck? Sure thing. Just be aware that the odds of committing a sin increase with each additional card. Need to retry a flubbed roll? No problem. Hopefully you’ll have leftovers when the real danger appears. There are even cards that break the game in more interesting ways, letting you ignore a keyword or overwrite something for another noun or verb. By certain metrics these would qualify as shoddy design. In a game like The Restless, itself about rules that have already been broken by the same beings that penned them, they feel like appropriate enough inclusions. Such cards soon sing their own siren song, inviting you to scour every encounter for weaknesses. Even a god may be undone with the erasure of the right codicil.

On their own, these details are peculiar. The grungy artwork, the card abilities, the expectation that somebody in your party will die and be replaced, even the ability to alter the game’s rules thanks to an uttered word — it’s in their summation that they create such an evocative experience. Even my reservations about the impossible-to-shuffle encounter deck were laid to rest. In most games, such a deep pool of possibilities would speak to a lack of focus. Here, everything is of a piece. Why should you not meet the Encouragement Pig while wandering the halls of some half-buried city? The Restless functions according to the bureaucratic logic of some nightmare where every law of physics and social requirement seem bent against you.

This dreamlike trance works in The Restless’s favor in other ways as well. When I call The Restless “evocative,” I mean that literally. Playing this game stirred two crises from the sulci of my memory. The first, when an unexpected illness wracked my teenage body and required heavy antibiotics over a period of months. The second, when I was at last forced to confront what I’d known for many years, that the underpinnings of my childhood faith were deceptions. These crises had felt the same because they were at root identical. They were both confrontations with the reality that I will age and wither and die, and be scraped from the parchment of existence like old ink, with no net rebounding me to heaven at the last instant. To live is to watch your forearms splotch with scars and the marks of the sun and bruises that will not heal before you die.

But to live is also, I hope, to speak directly to the face of god, or the universe, or our fellow persons, and leave some resemblance of ourselves even after they’ve planted us. Sometimes I meditate on the meaning of Andrei Tarkovsky’s belief that art’s function “is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.” In those moments, I think often about the billionaires who see only things and never people, or my coreligionists who carefully avoid the great body of work that is our species’ art, or the bros who think a machine could ever be worth conversing with, and it fills me with such a sadness that these people have so little faith in humanity — so little faith in their own holiness — that they will look upon the expanse of our experience, those horizons, stretching on and on and never stopping, and say, “I’ve seen enough.”

In The Restless, our party is doomed from its founding. Why, then, do we persist through the ashes and the arteries? Why do we elect to face these stillborn horrors rather than curling in the dust and waiting for the cosmic backwash to swallow us back down? Even success is failure by another name.

It’s because we are not the restful. The game’s title is not a curse, but an invocation. We will set our feet into motion, it says. We will imbue our last movements with purpose. We will carve some message into this parchment, some autograph that may be recovered if only as a palimpsest. We will walk ahead of the falling seawall, and witness firsthand the crumbles of our world, and speak into the face of god.

This is The Restless. It’s a bleak, ugly, and strange game, the product of an industry outsider who thankfully doesn’t know the first thing about oversold concepts like “good design.” It is a travel game about unlikely comrades, the toll of inevitability, and lots and lots of dice-rolling. I think it’s an absolute gift.

The Restless is on Kickstarter right now. You can find it here.

A prototype copy of The Restless was provided by the designer.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my second-quarter update!)

Posted on July 14, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, The Restless. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

Wow! Sounds fantastic! As a long-time fan of Cave Evil, this seems like something right up my alley. Thank you for the great review and heads-up!

Of course! I’m never happier than when I’m highlighting weird stuff that might otherwise go overlooked.

Aw man, someone already stole my “Wow!” response. Well then…Zowee! I don’t always bother to mention that you’ve written a great review, because that would get repetitive, but this was a great read, sir. And, as always (unless it’s a trick-taker), you’ve tempted me to spend more money, so you’ve done your job. That’ll do, pig. That’ll do.

Hey! It’s also my job to save you money! I’ll write a negative review tomorrow just for you.

Thank you for this! I backed right away. The add-ons are amazing as well. I love the tote bag and the photograph pin especially.

I’ve heard that from a couple of folks! I haven’t taken a look at the campaign yet, but I’m eager to see what the hubbub is about.