Stuck in the Midden with You

The oldest known evidence of human habitation on the Orkney Islands, the archipelago off the northern coast of Scotland, is a charred hazelnut shell and some thousands of flint fragments, variously dated to either the seventh or eighth millennium BCE. That’s a long time ago. A dang long time. Later evidence is more impressive, standing henges and stone farmsteads, but those simple tools confirm that humans first came to Orkney not long after the glaciers receded to hunt, forage, and eventually heap together so much garbage (mostly shells) that later generations would repurpose the refuse into the foundations for their settlements.

Skara Brae, named for the largest of those settlements, is another historical title by Shem Phillips. I’ll confess I went into Phillips’ latest with some reluctance after Ezra and Nehemiah showed such a lack of care for its history. To my relief, Skara Brae is on surer footing, opening a limited but compelling window onto the daily lives of its characters.

Perhaps it also helps that Skara Brae is far simpler than its Judahite cousin. At base, there are three dimensions to Skara Brae, but Phillips keeps them mercifully shorn of ornamentation, allowing each to circulate among the others and present a textured experience that never grows overly woolly.

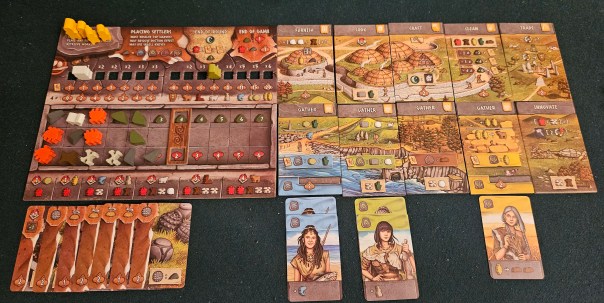

The first portion is the simplest of the bunch, three drafts spread across each round. Players are presented with a handful of options, mostly villagers they can invite to their settlement, but also the occasional set of stone balls, sheltering rooftops, or food-preparing utensils. Everybody picks one for themselves, then moves onto the main attraction for the round.

But we will linger, if only momentarily. Phillips approaches these drafts with an admirable sure-handedness. Not only are they restrained, they’re also enlivened with a novel passing system that allows someone to delay their current pick in order to secure an earlier position in the next set. Since all three of a round’s drafts are arrayed in advance, this is no small consideration, pitting the current picks against those you’ll mull over in a minute or two.

The same goes for the cards themselves. Villagers are the punchiest of the lot. The more you welcome into your home, the more resources they gather. Each also offers a one-time ability that nabs something more worthwhile, a rabbit or fish, perhaps even the option to swap some grain for a cow that could feed your entire settlement for a year. The tradeoffs, however, speak to a tyranny of the calorie that would never be far from such a community’s thoughts. Villagers need to be sheltered and fed, increasing the burden on your camp. This makes the other options worthwhile in their own right. Utensils increase how much you can cook at a time, while roofs make it easier to shelter your growing tribe. Carved stone balls might not seem like a big deal by contrast, but hey, culture is culture. Who doesn’t love bocce?

This material approach is also found in Skara Brae’s other elements, the second of which is your storage space. This is also where Phillips really begins to distinguish his game not only as a plaything, but as a bone fide expression of what it took for Neolithic settlements to thrive.

Unlike some games about resource conversion, where seasoned players might run a series of swaps in their head before actually grabbing anything from the supply, Skara Brae asks its players to physically claim each token. That’s because your inventory is severely… not limited, that isn’t the right way of conceptualizing it, but prone to overflowing. As resources are gathered, they’re placed in your storage bin. I know, I know, that goes without saying. Your bin, however, has a cap that slides upward whenever you breach its limit. Your actual storage space can accommodate quite a few shells, bones, and foodstuffs, but pushing this container’s lid ever upward presents its own problems.

Namely, midden.

Ah, midden, every archaeologist’s favorite discovery. These are garbage dumps, basically. Famously, the Orcadians built settlements over the top of these heaps, digging into the compacted slurry to produce insulated foundations. In Skara Brae, midden is your garbage. The higher your storage cap, the more trash you produce each round. Not only is midden worth negative points when the game concludes, it also sits in your inventory like a freeloading college grad, hogging up space and contributing nothing. You can’t eat it. You can’t trade it. You can’t even dump it into the sea.

(Side note: Sam Phillips’ lovely illustrations show Skara Brae directly adjacent to the shore, the way a visitor might see it today. This is a sound aesthetic choice, emphasizing the importance of the sea to such a settlement’s survival. But in the era presented by the game, water levels were lower thanks to greater volumes of sea ice, placing Skara Brae and other Orcadian homesteads farther inland. While a fisher would gladly bring their catch home, garbage dumps tended to accrue closer to the village. Even in the Neolithic, nobody was clamoring to clean up after dinner.)

What you can do with all that midden is repurpose it into houses.

This brings us to the third and final of Skara Brae’s dimensions, a worker placement segment that initially sees you assigning a single sturdy worker to a job, then gradually growing your settlement until you have four hardworking homesteaders bringing home food and construction materials, and using those resources to improve your place in the world.

As worker placement systems go, this one’s dead simple. You have one big worker. Eventually this big worker begets three small workers. Your big worker can be placed anywhere, while your small workers apparently refuse to share space or they’ll go all Cain and Abel on each other. The destinations in your village are similarly easy to operate. You can furnish your home, increasing the comfort of your villagers and therefore their scoring potential. Cooking transforms fish, grain, rabbits, and deer into meat, bones, and hides. There’s an option to trade, a great way to part with all those bones that come with your food. And for good measure each player gets their own unique option, ranging from boar-hunting to spinning thread from all that wool.

In the game’s early stages, survival takes priority. So you gather. And gather. And gather some more. This pushes your storage limit upward, which in turn produces midden. As your settlement becomes more established, you hit an inflection point. Now it’s time to gather inward.

This is where the “clean” option comes in. Rather than drowning in your own filth, you can dedicate resources to clearing midden. Except you aren’t exactly “clearing” it. In the same way that slaughtering a cow transforms the animal into distinct but not materially dissimilar resources, clearing midden transforms it into a roof card. Thus midden is the game’s most crucial resource, diminishing your village’s quality of life but also paving the way to self-sufficiency. Little by little, survival gives way to culture and comfort. And all along, the secret ingredient was garbage.

This speaks to something true about human society, whether we’re talking about Neolithic gatherer camps or farmsteads that dug their homes into hillsides of garbage, Iron Age settlements that melted down every bent buckle or dulled knife, Middle Age burgs that reckoned with the flow of human waste, or modern societies with our landfills and sewer systems. The quality of our garbage, how it’s used, removed, treated, repurposed, mined, or ignored, is a subtle but effective measure of that society’s lasting health. Nowadays we consume roughly a bottle cap per week in microplastics. It’s in our blood, our semen, our organs, our brains. Hopefully somebody puts a worker on the cleanup card.

In that respect, Skara Brae presents an interesting parallel to an unexpected title, Phil Eklund’s Greenland, itself about human societies struggling to survive the reign of King Calorie. Greenland, like Skara Brae, adopted a long view of history. Each turn covered a full generation. Its antagonists were sometimes human, tribes occasionally coming to blows over limited hunting grounds, but also drifting sea ice and animal extinction.

If Skara Brae has one deficiency, it’s an absence of pressure. As I wrote when the game first released, Greenland excelled at presenting history as a sequence of random events, arguing that human success was as much a question of chance — it was a dice game, after all — as one of determination and innovation.

Skara Brae turns its vision inward to a single settlement over a shorter span of time, precluding any Little Ice Ages or Norse invasions, but even there it elides many of the pressures that would weigh on such an encampment. The exception is found in its solitaire mode, which provides a handful of focus cards. These speak to your village’s needs and desires, forcing you to spend specific resources over the course of the game lest you sacrifice some number of points. It’s a brilliant method for abstracting a wide range of possible occurrences, from inter-family squabbles to wanderlusting teenagers, without adding any significant weight to the gameplay.

Sadly, both play modes leave something by the wayside. In solitaire, one misses out on the full depth of the card drafting, while the multiplayer lacks the focus cards. Call me a glutton, but I would have preferred to wrestle with both challenges at the same time.

On the whole, I’ve been thoroughly impressed by Skara Brae. I love its dedication to its time and place, its bright aesthetic, even the way its (bazillion) resource tokens form their very own midden pile. Shem Phillips has crafted something special, a limited but crisp view of an optimistic society, one that thrived despite stark limitations, in part due to their willingness to repurpose their waste into something worthwhile.

Now to see how much longer we can shunt all of our workers to the “ignore the problem” space…

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read the first part in my series on fun, games, art, and play!)

Posted on May 29, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Garphill Games, Skara Brae. Bookmark the permalink. 7 Comments.

Great review as always Dan. This arrived, along with The Anarchy, yesterday and looking forward to it hitting the table soon.

Garphil games are now pretty much a must buy for me and so far I haven’t sold any on. Although Hadrian’s Wall may be ousted by The Anarchy.

I really enjoyed Ezra & Nehemiah as a gaming experience but not being a man of any particular faith was not aware of the historical liberties until I read your review of that title.

Keep up the great work – your reviews always bring a unique perspective on games and their broader context in historical and sociological terms that makes them a fascinating and sometimes educational read.

Thanks for the kind words, Steve. To be fair, my faith background not only inherits the textual assumptions and problems of Protestantism, but introduces a whole slew of new ones! In fact, it was Mormonism’s very weird perspective on Biblical history that convinced me to peek down the rabbit hole. A few languages and degrees later, it’s mostly served to make me an insufferable pedant when it comes to portrayals of antiquity in board games.

Good review 🙂

Also, as an aside, looking out of my office window just now and can see Orkney from here 🙂

Whoa! I have a view of the mountains, but sometimes I wish I could see the sea more often.

great review as always Dan, i’m very interested in this one since it was announced, mainly because the resource interaction seems such a fun puzzle to try to solve. But now I’m wondering if there is a way to introduce the solo cards to the multiplayer game, I didnt read the manual but doesnt seem far-fetched to me to just give one problem card to each player in a round and let them deal with it also.

I’m sure there’s some way to port the solo cards into multi. It couldn’t be a strict 1:1 port, unfortunately, because there aren’t enough of the things for four players!

Pingback: Best Week 2025! Picture Perfect! | SPACE-BIFF!