Inhale & Exhale

My game group has an inside joke. Anytime Geoff comes over and sees hexes on the table, he’ll say, “Oh, we’re playing Archipelago?”

Rise & Fall is the first time I’ve been able to say, “No, but it was designed by the same guy.”

I’ll confess, though, that Christophe Boelinger’s latest effort has me befuddled. Part civilization game (but only a sliver), part area control game (a much bigger slice), there’s an undeniable elegance to the whole thing, almost a throwback quality in its absence of chance and willingness to turn players over to the mercy of its spikier edges. Which is maybe why I’m surprised to say that my favorite part of the endeavor is the setup.

To be fair, the setup for Rise & Fall is killer.

It’s a little bit like watching a map generate in an older civgame, continents and lakes and mountains clustering together to form the landscape you’ll soon be jostling for control over. Each player receives a certain number of tiles. First the oceans are placed, branching off at strange angles rather than marking a tidy circumference. Land is next, first lowlands and then forests and mountains and white-capped glaciers. It’s like enacting some Biblical proclamation. Let there be hexes.

Eventually, players plop down their starting pieces. Everybody receives three. A city, a nomad, a ship. Unlike any civgame out there, these are best spaced far apart, better to give you a toehold in this world’s far-flung corners. And lest you think that these placements can be made flippantly, everything rides on their merits. Even when those merits aren’t all that clear.

It’s a portent of what’s to come. Already the map has developed its own essential topography. Some regions are already worth more or less than their neighbors, marked by elevation and geography. Natural bottlenecks have been shaped, not only by the placement of water, but via rises too steep for most units to climb. More than most board game maps, the place feels vibrant, full of quirks and exploits and high-value targets. It’s a landmark process. Heh.

I’m somewhat cooler on what follows, but it’s hard to explain why.

The actual mechanisms are shaped with clockwork precision. Acting at the same time, everybody selects a card that designates which of their unit types will activate that turn, then goes around in turn order to take those activations. The selection is surprisingly fast, especially thanks to a nasty little rule where if everybody selects their card but one person, then everybody can count to three and then select a card at random for that player.

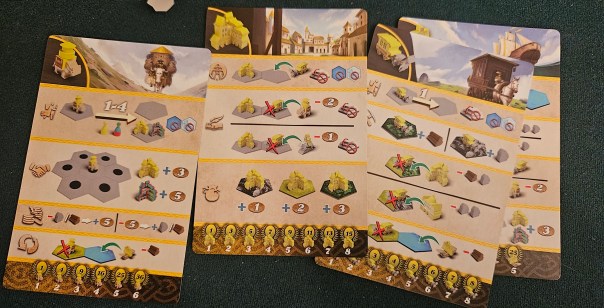

Actual turns, on the other hand, tend to be more deliberate. There simply isn’t any room for a misstep. Each unit type offers its own range of options, and although the cards initially seem crowded, the units soon reveal themselves as mnemonic masterworks, each imbued with their own sense of purpose. Nomads trundle slowly across the landscape, gathering wood and stone, founding cities, sometimes transforming into boats. Cities spit out nomads and other units — more on them in a second — and generate cash depending on where they’re located. Ships also produce coins, but can also beach themselves to become nomads or merchants.

Along the way, there are little touches that give each unit its own personality. On the table, each has its own silhouette, making them easy to pick out, and their gameplay effects are even more pronounced. Mountaineers, the cute little tiger-riders, can found cities, just like their nomad cousins. But where nomads require wood and stone to settle, and are limited to founding them on lowlands or forests, mountaineers pay wood alone and can found their cities up in the mountains. Merchants earn heaps of gold and are the only unit that can double up on occupying a space, making them essential not only for padding your treasury, but also for contesting a rival’s control over an otherwise cornered acre of terrain. Temples offer the game’s sole act of outright aggression, letting you convert rival pieces to your side. In practice, this is more useful for locking down an area than for actually flipping units, although that’s a significant boon in an area control game this hotly contested.

The big wrinkle is that you’re only ever holding cards for the units that are currently placed on the map. Because you have three unit types on the board when the game starts, that means you only have the corresponding three cards. Furthermore, if somewhere in your first few turns you should transform that starting ship into a nomad, then your ship card will be set aside. The benefits to such a maneuver are immediate. Now you’ll be working with only two cards, bouncing between them rapidly rather than having to wait for that third card’s cooldown before everything cycles back into your hand.

Then again, because this is a Christophe Boelinger game, there are risks to such an approach. Ships might not provide the bombshell growth of nomads or cities, but their initial value is found in their steady trickle of gold. At regular points, somebody will trigger a decline by placing all of their pieces of a certain type on the board. Now everybody is forced to lock one of their cards away on the side of the table, victim to the “fall” half of Rise & Fall. These can be ransomed back for gold, but their price increases with each decline. Paying five gold isn’t such a bad deal, but ten? Twenty? Forty? That’s steep, especially since coins are also worth a lot of victory points. But the alternative can be worse. If you don’t have enough to pay the ransom, or if your hand is too trim, you might be forced to pry an essential cog from your engine for the foreseeable future.

Smart players can leverage these seismic shifts to their advantage. Declining a card you weren’t using much anyway isn’t such a bad thing, and it’s often desirable to field some units that don’t gel with your plans so that an unexpected collapse doesn’t deprive you of an essential unit right before you put it to good use.

It’s smart. So smart. Painfully smart. Charting a course through Rise & Fall isn’t only about maximizing your growth, isn’t even only about dumping the notion that this is a civilization game in order to focus on its area control core. It’s also about keeping both eyes on your rivals to see when they’re approaching those collapses. I realize this is a strange metaphor, but I’ve come to think of it as a game about increasing one’s lung capacity. Your expansion is the inhale, always growing rounder and fuller. Your hand of cards is the control you exert over your diaphragm, keeping it tight but allowing enough wiggle room so you don’t seize up. And weathering a collapse is similar to seeing whether your exhale comes out measured or sputters into a cough. It’s rhythmic. Hopefully in a way that lends itself to frog-breathing into your mellophone for two straight minutes because the marching band director is a sadist.

For all its smartness, I don’t believe I’ve ever had a session of Rise & Fall that wasn’t as infuriating as it was admirable.

There are a few issues I might point to as pressure points, but they’re largely superficial. Like the way its rotating player order is crucial but swaps at uneven junctures, or how the endgame arrives with a slam rather than signaling its approach. Small things, in other words, possibly not even proper problems, but nitpicks that loom large when I start asking “So why don’t I like this game?”

The truth is that I’m looking for a reason. Because, in the end, my issue with Rise & Fall isn’t something it does poorly. It’s that what it does well it does so well, with such an unyielding application, with such devotion, that I find it frustrating for its identity rather than for the ways it fails to live up to itself. But there it is. I dislike how it revolves around population explosions, nomads and cities replicating one another in expanding spirals. I dislike how it penalizes experimentation, instead leaning into tailored action sequences and precise outcomes. I dislike how it’s so tightly wound, a rubber-band ball on the verge of snapping, that someone playing poorly to my left often spells utter victory for someone to my right, that merely by having somebody wander into my ocean rather than somebody else’s, I might be thrust into an arms race with no winners except the third party who’s slowly gobbling up his own portion of the map.

I realize these are player problems, or perhaps not even problems at all but emergent properties of the game being played exactly as intended. Rise & Fall is, among other things, one of those games that rewards sharp play, not only from you or I, but also from the peers seated beside us. It works best when everybody is firing on all cylinders, matching aggression for aggression, treating every runaway player as someone to horn in on rather than a threat to be avoided. It’s a gamer’s game, but that’s precisely why I struggle to get along with it. It reminds me of when the latest multiplayer shooter leans even harder than its predecessors into twitch reflexes. It’s uncompromising in its focus, the ethos of board games as optimization taken to their extreme. I can see the beauty of this thing. I also find it obnoxious to actually play.

Those actual plays, it turns out, are never close contests. They’re runaway grocery carts. Somebody overturns their cart early and gets left in the dustbin of history while everybody else forges ahead without them. They then spend the next hour or so — because Rise & Fall is not overlong but wraps up in a tight ninety — trying to patch their kingdom back together again. It’s hopeless. But they try.

Along the way, my prevailing emotional response is annoyance. Maybe some guilt, too, every time my temples convert another of that flailing player’s merchants. Their frustration becomes my frustration. It’s a game I can win, but it has yet to become a game I feel good winning.

Again, this is a player problem. It’s a me problem. I know that. But I can’t shake it. The more I play this thing, the more I grow dissatisfied with it. In the end, Rise & Fall is a work I enjoy in the abstract. Just as it relegates its civgame trappings to the wings, it’s an impressive piece of craftsmanship at every level, one which I will continue to admire — from a safe distance.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my quarterly report on all things board games!)

Posted on April 16, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Luidically, Rise & Fall. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

That sounds very much like the feeling of Archipelago. Genius but abrasive.

I’ve only managed a single play so far, but Rise & Fall instantly impressed me as a *great* euro—one that channels the spirit of the old classics while still feeling modern, in a OG/SICS way. The game’s organic growth, tense shared board, and sharp player interaction really stood out. As a fan of Hansa Teutonica, Bus, and Food Chain Magnate, I loved how Rise & Fall captures some of the same DNA: you try to build your position, carefully planning your moves, and then -whack- you get blindsided by a neighbor’s clever play.

What I appreciate most is the way every move matters, for you and everybody else. There’s little in the way of artificial catch-up, so every decision feels meaningful and the competition is fierce. I’m sure it will only get richer with repeated plays. Highly recommended for anyone who loves interactive, sharp euros…

I don’t tend to love games where “every move matters” in the sense you describe here. It often means that a single mistake can cause the rest of my decisions to no longer matter. (To me — they’ll still make or break the game for my opponents who haven’t made a major mistake yet).

I do love high difficulty and high stakes sometimes. It makes every move feel thrilling and tense. But… I usually love that in the context of single-player games, usually videogames. In that context, if I slip up and guarantee an eventual loss, I can call it a game and move on with my day, or restart and try again, or use my forfeited attempt to experiment and take risks I normally wouldn’t. In a multiplayer game, I can’t do any of that without ruining the game for everyone else.

I think the fact that he designed the game for him and his wife to play speaks a lot in answering some of the issues you raise in your review Dan. To quote Christophe himself in an interview:

“The starting point was in 2018. It had been five years that I had been with my wife. I met her in 2013 and she’s a Brazilian from the Favelas in Rio. On her Facebook page, she had written that she hated games. Wow, that was tough for me, because it’s not only a hobby, it’s my job! She hated games. But she was thinking about video games and games that you play in a bar, to bet on or things like that probably. She didn’t even know that the board gaming industry was so vast with so many games. The only game she knew was Uno and maybe one or two easy other ones like that, the really mainstream games.

So when I met her, she started to see that gaming was more than what she had thought. I started slowly to introduce her to gaming and in 2018, she was starting to play games that were more expert type of games. She had never played a Civilization game, a big one with all the things. So I designed Rise & Fall for her and me – very, very selfishly I would say. I wanted to have full control because I love full control. Dungeon Twister has no randomness. One of my favourite games is Full Metal Planet, no randomness, zero, perfect information. So I wanted a perfect information game. I wanted something that I would really enjoy myself, a not too complex nor whole-night Civilization game, but with quite some options. And I wanted it to be so easy that she would get into it and she would love it just because it’s easy, instinctive, and almost everything is summarised on what you have in your hand. I wanted all the rules to be on our set of cards that we would play every turn. I wanted her to never have to go back to a player aid. Everything had to make sense.”

[I got the above here: https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/3476113/origin-stories-rise-and-fall-an-interview-with-des …]

Also a bit like chess perhaps this game is meant to be a 2 player game. So there’s less feeling bad about messing up someone else’s position. Perhaps.

Fantastic!

Love Christophe’s work…

I was a backer who got caught out with the lack of precise notification of the PM close and missed making my payment. I’ve been annoyed by the rather derisive response Ludically offered backers who tripped at this last hurdle ever since so your review helps my mitigate my disappointment a great deal 😁.

All the best.

Pingback: Better to Live Under Robber Barons | SPACE-BIFF!