Three Phases of Six Moons

The past is not a foreign country but an act of imagination, one that can have greater or lesser fidelity to something that once happened, but one that also remains forever out of reach. The best we can do is stretch and maybe, just maybe, graze fingers with the unnameable.

Like true history or old starlight, City of Six Moons is an unrecoverable thing. Created by Amabel Holland, this is a radical design from a designer known for pushing boundaries. By now you may have heard of the game’s conceit: in a medium defined by its attempts to crystallize authorial intent as perfectly as possible, City of Six Moons is instead presented in a foreign language, offered to Holland by alien visitors and then transmitted to us as a signal garbled over the airwaves. Somewhere underneath the static is a playable game. On our plane, the designer refuses to clarify any rules or offer correction.

Over the past four months, I have grappled with City of Six Moons. I have studied its rulebook by lamplight and fallen asleep with its symbols dancing under my eyelids. This is the story of how I translated the game — or, perhaps, how I didn’t.

Phase One: Incomprehension

I have worked as a translator. My specialty is a particular subset of dead languages, all of them Biblical. Translation, especially translation of languages nobody speaks anymore, relies on an abundance of context and comparison. When you see a word inked on parchment or wedged into clay, it isn’t enough to open a dictionary and read its meaning directly. Instead, one must investigate what that word meant in that particular author’s time and place. Words change meanings in all sorts of ways. Sarcasm, double entendres, contronyms… human language produces no shortage of trouble. That’s why the more often a word is repeated, the more clues it offers about its intended meaning.

But there’s a particular terror for historians of my stripe. We call it “hapax legomenon,” which means something that only comes down to us once in the historical record. For whatever reason, these words or turns of phrase only appear in isolation. Without the discovery of other documentary evidence to compare them against, these become errant islands of meaning. Their function can be guessed at, but only imperfectly.

When I first opened City of Six Moons, the entire thing felt riddled with hapax legomena. Certain details were easy enough to suss out. Page numbers, for example, or symbols that indicated verbs such as add, subtract, or choose — although even these observations relied on the assumption that our aliens were predominantly right-handed, conceptualized language linearly, and had developed their symbolic shorthand according to the same rubric that Western board games have settled on. What a nightmare it would be, for instance, if instead of their version of a plus sign meaning “add this thing,” it meant “these two things now become one.” You know, the way it can mean in our own language.

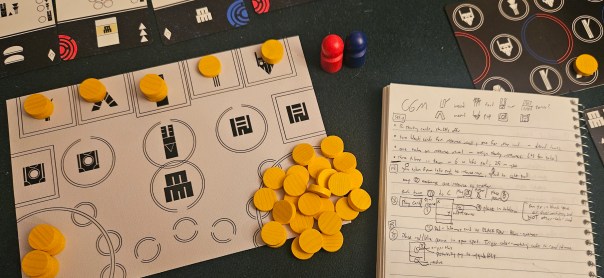

But on certain points I was stumped. This was the hapax legomenon. Without any clear distinction between the rulebook’s internal symbology and the external components it was referencing, I couldn’t determine whether my copy — one of the first to ship out the door, as Holland had sent me an early copy for review — was missing a vital component.

Context. Comparison. How do we recover a dead language without the benefit of ongoing tradition or a Rosetta Stone? The answer, it turns out, is that we don’t.

Determined to examine this artifact on my own, I lasted a week before deciding my stubbornness was counterintuitive. There are two ways to approach a puzzle like this: as a test of one’s own cleverness or as a measure of collaboration. I had been so fixated on the idea that City of Six Moons should be solved individually — could be solved in isolation — that I was forgoing a valuable resource. So I glimpsed at the photos someone else had posted of the game.

Sure enough, there was the missing fragment: a canvas playmat. I reached out to Holland. “Oh my God,” she replied immediately. A week later I had the missing piece. It wasn’t a Rosetta Stone. More of a Rosetta Sliver. But it was enough to begin in earnest.

This was frustrating. Of course it was. But I wouldn’t trade that initial confusion for anything. It had highlighted two important points.

First, this is where all translation begins — not with actual translation, not even with one or two words, but with the assembly of the proper materials. Had I washed up on a beach and found myself face-to-face with a stranger, we would need to begin with the things around us. Stick. Sand. Grass. Tree. But even those early assumptions might be wrong. What if instead of stick, my new friend said “support”? “Ground” for sand. “Livestock-feed” for grass. “Tall” for tree. Each term might represent something concrete, but it could instead depict something cultural or conceptual. Maybe even snarky, because if there’s one constant between cultures it’s that boys are going to say “Biggus Dickus” when presented with a fat stick. Before I could begin translating, I needed a sufficient framework to not only guess at the meanings of various symbols, but double- and triple-check them.

On a more ludic note, it also got me thinking about the boundaries of the game itself. I write a weekly thing on social media where I mention the games I’ve been playing and let people ask questions about them. When I noted that I had been playing City of Six Moons, everyone’s first response was to inquire about the game. Not in the abstract, but concretely: “How does the actual game play? Is it any good apart from the translation stuff? Is there any reason to keep playing after you’ve figured it out?”

But I hadn’t played City of Six Moons. I hadn’t even really started my translation. I’d done the equivalent of rummaging through its components and sending a component replacement request to its publisher. At the same time, I felt like I had been playing the game for two weeks. So where, then, is the game? What are its boundaries? When players select their starting cards, is that play or setup? When somebody teaches us the rules, are our varying degrees of attention as much a function of play as the action-points and cube-pushing that follow? Taken to its most extreme, are we playing a game when we punch out its components? Are we playing when we think about it?

What is the game?

Phase Two: Translation

To answer that last question, we need to acknowledge the limitations of language. Here on the internet, one of our favorite pastimes is to argue over what “counts” as something. What is a chair? Which books fit into canon? Who is a true Scotsman?

Except things don’t always fit into their assigned containers. Categorical definitions bind things together, but grow sticky once we start using them too strictly. To some degree this is counterintuitive, especially to modern minds that accept strict concepts like medical or natural taxonomies, where precision is valuable and potentially even life-saving. But we aren’t talking about dosages or chemical chirality. We’re talking about behavior. We’re talking about people.

Here’s an illustration of the problem. Like many hapless parents before us, Summer and I have tried to instruct our children that cleanup is part of play. Like untold billions of children before them, our kiddos instinctively reject this proposition. They’re too smart by half to fall for that trickery.

Except something wonderful sometimes happens when I dive into the cleanup routine with them. I throw their dirty pajamas so high that they hit the ceiling, raining down on them like an overturned hamper. We toss objects from one to the other, in the style of a bucket line dousing a fire, gradually creeping their toys closer to their receptacles. We pile towers with their blocks and legos, but only at their final destination. Then, when the timer goes off or the living room is clean, sometimes my five-year-old shouts that she doesn’t want to stop. Cleanup is no longer anathema to play. It isn’t even a part of play. Cleanup is play.

For me, translating City of Six Moons fit into two overlapping categories. They bled into one another, as categories do in the wild, and in turn resulted in a game that’s as much about me as it is about Amabel Holland. Or the aliens that gave her this game. Whichever.

The first category is that of a puzzle. I don’t know the touchstones that led Holland to create this thing, but it evokes the deliberately unelucidated rules of Blaž Gracar’s LOK and Abdec, the fragmentary rulebook of the video game Tunic, even the half-understood rules of a family board game like Uno or Monopoly, passed along orally rather than studied carefully.

In this mode, Holland threatens to overwhelm players. Unlike LOK or other puzzle games that ask players to teach themselves the rules one trickle at a time, City of Six Moons hits players with a blast from a fire hose. The rulebook isn’t large, only seven pages plus Holland’s in-universe production notes. Without any explicit meanings, however, it can loom as large as an ocean. Like facing down a research project, the task lies in figuring out how to swallow the elephant without unhinging one’s jaw. I began with the most digestible morsels: digits, verbs, nouns. Placeholder titles served well enough for the time being. One resource looked like a tree, so I termed it wood. Another looked like a rudimentary dwelling; this one I titled stone. An alien face became population. Swaying stalks, food. The two more abstract resources, which resembled nothing so much as companion cubes from Portal, I labeled Super and Duper.

One of the first things history students learn is that every history book is really telling two histories, the history it wants to tell you and the history of whomever wrote it. What does it say about me that the genesis of my translation was spoken in the language of civilization and exploitation? There is no concrete reason why these icons should be resources, nor that they must be gained or spent, but rather transferred, traded, shared, evaporated. Maybe we’re assembling an organic computer. Maybe we’re a hivemind trying to resolve an internal disruption. In someone else’s hands these resources might have been fragments of stories, or seasons, or stolen moments between lovers.

Not in mine.

In my telling, City of Six Moons was a contest between city-states. This is the second category of its translation, that of the story’s attachment to something recognizable, both via storytelling and play. Truly there is no other way to translate a board game than to play it, to arrange its pieces and navigate their interaction, to see which movements feel natural and which gash like a wound across its tissue. This is like learning a dance, feeling the rhythm of things. Again, a supposition on my part: that there should be a rhythm, and if a rhythm then one that taps to a familiar meter. Counters move from one stockpile to another; are gained from left to right; are spent to the underworld. Cards are earned and slotted, or else disrupted by a vague third-party intelligence that sets the game’s tempo. There is a tableau — really three of them — which is triggered by pawns and periodically refreshed.

The words have become sentences, then paragraphs. Now, at this point, I could tell you the rules to my version of City of Six Moons. I could explain what everything means. And you could play it.

Phase Three: Invention

Linguistically, we delineate between prescription and description. The former concept, prescription, holds that there are firm grammatical norms that ought to be observed by all users of that language. Description, on the other hand, argues that grammar can only be observed, never enforced.

Living languages always fall somewhere in the middle. I think of the word “nonplussed,” which once upon a time meant that somebody was surprised or confused. Over time, likely thanks to its negative prefix, people began to use it to mean that they were unsurprised, exhibiting a flat affect in response to something. This is how a contronym is born. English is riddled with self-contradictions like this. Cleave: to come together or to tear apart. Bolt: to lock in place or to flee. Dust: to sprinkle or to clear away.

In translation, especially historical translation, one never forgets that languages are both things at once, both strict boundaries maintained by stern scribes and playful acts of invention where meanings are constantly negotiated and altered and inverted, whether on purpose or by accident.

Irving Finkel famously recreated the Royal Game of Ur when he translated a cuneiform tablet that spelled out its rules. His recreation is prescriptive in one sense, fitting the rules as pressed onto the tablet. But it’s also descriptive. Finkel developed his first Ur board at the age of nine. Even when he was forcing his sister to test out hypothetical rules, he was brushing fingers with those who played it two thousand years ago. He drew on his own assumptions from other genre examples, race and contrary-motion games like backgammon. By the time he was old enough to translate cuneiform, the game already existed in his mind. As he describes it, the Royal Game of Ur would be played in bars and courts, gambled on by peers or passing merchants. They would quibble over rules. They would invent and reinvent it as they went along.

Eventually, this is what happens in City of Six Moons. At least it’s what happened to me. I recreated the game as far as I could take it. There are no more symbols in the rulebook that don’t have attendant translations. But there are still things that simply can’t be known with the current information. These are not hapax legomena; they’re blank spots, cultural lacunae, ambiguities.

Opportunities.

I began to answer their call. When the rules show a disc being placed atop another, but only when there’s only one disc on the bottom half of the equation, does this mean that two discs are the maximum that can be stacked in a particular spot? I decided in the affirmative as a means of regulating my rival city-state’s growth. In the section that appears to teach players how to tally points, does that specific instance of that one symbol mean and or with? The distinction matters. I’ve tallied my score both ways and decided I prefer the latter. Are the digits on page six intended as targets or thresholds? We will never know. I made my own call.

This is the final and most resolute truth behind City of Six Moons. When we set out to understand another mind, we always create. Our lovers will be idealized, our enemies more despised. The Ancient Rome we think about every day will look suspiciously like whichever empire we occupy right now. The artifact we produce will be a mirror, but that’s an impression of history, too, because the person who spoke this thing into existence was also in the mirror business. By doing both things, prescription and description alike, faithfully reproducing the text while creatively filling in the gaps, this is how we brush fingers across time and space, how we return to the dead the gift of immortality. I cannot recommend City of Six Moons to any but the most enterprising, but I’m so glad to have spent a few months playing it. Even, especially, when it got into my head rather than staying on the table.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on October 25, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Amabel Holland, Board Games, City of Six Moons, Hollandspiele. Bookmark the permalink. 19 Comments.

Thank you for this Dan – I love your reviews. The way you’ve described 6 Moons makes me think that all rule book interpretation is a creative act. I can’t think of a game where we haven’t had to argue about ‘must’ or ‘should’ etc. often we’re straight onto the internet to how others have interpreted the rule. Holland is a genius and you are a great translator of the experience of games. Thank you.

Exactly! Every so often, I’m amused when somebody drops a thread on r/boardgames about how they’ve been playing such-and-such game incorrectly for years. But they were playing, and presumably with enough internal consistency that they never noticed the error. That makes them accidental designers of their very own variant!

I’m deeply tempted to ask about details of your copy. The conceit of Six Moons being a traditional game, and therefore there being some local variation is at once delightful and infuriating. Especially from the mindset of interpreting the rules being a puzzle, which can be hard to let go of.

Yep. I took a look at someone else’s “cheat sheet” after writing this review, and there are a few big differences between our rulebooks. That’s another big hurdle with translation: everybody is speaking the language they know, not some universal tongue. I can’t decide whether that’s Amabel “patching” her game with later releases and falling back on the subjectivity of the whole thing or shitposting or what.

Like “Maybe there’s a cultural assumption that a number that’s too big on p2 just means ‘all the rest?'”

I do think some rulebook variation is intentional, and I do kind of love the mischief of employing POD that way. But your point about hapax legomenon is well taken (and the term itself was much appreciated), an exacerbated by that variation. But also, I think that’s very much her intention. We’ll never know if we are playing the game “as intended” – and that’s the deeper intent.

I hate to pull back the curtain but the idea that I am patching or that the versions are sequential does really bother me because it implies a “real” or “canonical” version existing alongside inferior ones rather than presenting equally valid but distinct regional versions.

Interesting! Thanks for the peek behind the curtain.

Thanks for this review Dan – as I often do with your reviews I learned a lot from it, on top of what the game is and has to offer. I was tempted when I first heard about it and I would love to be good at things like this. Sadly I think I would just get bored and frustrated. Great to know games like this exist though.

Right, I don’t think this one is going to be for everybody. Even considered as a puzzle game, putting everything into a single grab-bag rather than walking players through steps of increasing complexity, the way Gracar does with LOK (as opposed to Abdec, which proved too tough for quite a few folks!) is a big ask.

Thank you for this Dan, I was waiting for your thoughts and you didn’t disappoint! I really appreciated the framing and detail around dead language translation.

From my side knowing this was a designed experience allowed me to lean onto some boardgaming rule preconceptions, at least to get started. Once the cross referencing of the manual is exhaused, the creative and occasionally collaborative process of testing and sharing ideas for me was where the game took off. House rules made up on the fly or decided before the next game, or like you said choosing the interpretation that best fits the theme. It tapped into that creative space we get lost in sometimes, like making tidyup the best game. I really appreciated that anecdote by the way!

With no final definative interpretation, the game forces creativity to be part of the experience, and to iterate that creation too.

I likened City of Six Moons to each players personal Frankenstien’s Monster, they all look similar, slighly boaardgame shaped, but come to life in hesitant, stumbling and curious ways each slightly different from the last.

Thank you again for the article, and the detail within, it has enriched my experience of the game and boardgames in general, which you often do, but it is particularly resonant for the type of elemental experience on offer in this little box.

PS: I can only imagine the horror of not having a canvas board and trying to progress the puzzle!

Dan

Thanks for your thoughts, Dan! I’m always happy to hear that others are enjoying this one as well.

I have to ask, given your background on the subject – (dead) human languages – can you recommend any book on the subject? Either introductory or academical?

If there are too many to list, pick two. 🙂

Thanks in advance and regards from sunny Portugal

That’s a toughie! Nicholas Evans’ Dying Words is a fun read, and one that goes into some depth about the impact of language on how we conceptualize the world around us.

I’m so intrigued by the challenge this game presents with the interpretation and understanding of its ruleset. I imagine that process with a group of like-minded friends would make for an entertaining (and potentially frustrating) exercise. I’m putting this on my wishlist now.

I would love to have played this collaboratively with friends — trading notes, creating hypotheses, etc. It would be tough to assemble such a group!

Pingback: Catapults, Mostly | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Combined! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: A Desire for More Cows | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Space-Cast! #50. City of Six Amabels | SPACE-BIFF!