Man-Eating Review

Man-Eating House is a bit of a cryptid. Designed in 2016 by Kunihiko Tsuchiya, it did that thing where it appeared at Tokyo Game Market, generated some buzz, and then fled into hiding. Fortunately, it’s now getting a new edition courtesy of New Mill Industries. The remaining question is whether it’s a cool cryptid or one of those lanky goofball monsters that hides out of shame.

The idea behind Man-Eating House is that you are a… wait for it… actually, I’m not sure. Are you the man-eating house? Are you a ghost? Maybe you’re the children who have violated the boundaries of this place? Surely you aren’t the chainsaw or slingshot. Never mind. That would be sick.

Like plenty of trick-takers, the roles in Man-Eating House aren’t entirely clear. Still, it’s a suitably spooky setting, with its old house intruded into by hapless victims, a gaggle of ghosts who intend to haunt them, and the necessary accoutrements for either their survival or their doom.

Each of the game’s three suits arranges its ranks according to identical logic. The first three cards are victims. These provide juicy snacks to whomever wins the trick. Except — and let me tell you, “except” is the watchword here — when two or more victims of the same suit appear in the same trick, those meddlesome kids collaborate to escape the house. This awards them to their players’ scoring piles, removing them from the trick entirely. The same goes for the appearance of weapons. These defeat ghosts, normally the highest ranks, awarding them to the wielder of the most effective weapon. This turns the usual feeding order on its head. Suddenly it isn’t so cool to say boo.

Except (I warned you) when a dangerous location appears. These cards are rare, but they deprive the children of their ability to escape or fight back. Even the best-laid plans crumble when middle schoolers sneak into a haunted attic. Back to snackin’.

Except there’s also an Old Man, the nastiest card around, who’s unbeatable no matter what gets played. Is he evil? Is he good? Is he a true-neutral old man? He isn’t telling. (Okay, for sure he’s a ghost.) Point is, he takes the entire trick, no matter what.

Except there’s also your loyal dog, the lowest card in the entire deck. This good boy counts as a kid for purposes of escape. More importantly, he can defeat even the Old Man. Why? Rules of the afterlife, kid.

Except (!!!) each suit also has a creepy little girl in it. When played as the first card into a trick, the creepy little girl invokes Kagome. Because I don’t speak Japanese, all I knew about Kagome was that it sounded ominous. Then I looked it up and now my hair prickles at the word. Basically, imagine a Japanese nursery rhyme about swapping positions, with a blindfolded kid in the middle being circled by demonic oni. That’s what the creepy little girl does: everybody lays a card face-down in front of them, then the cards are passed either left, right, or across the table, presumably while a child sings a nursery rhyme about peeling your eyeballs. This can be a useful tool for collaborating with a teammate. It can also be used tactically to steal a powerful card. Like, say, the dog.

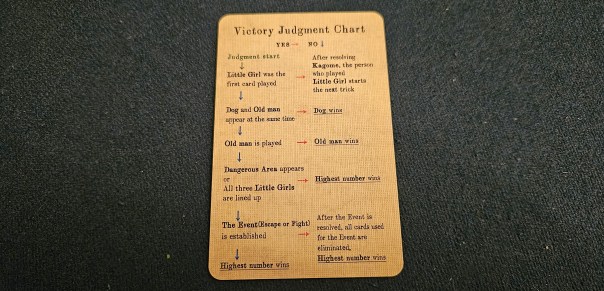

As you might expect, these exceptions threaten to overwhelm Man-Eating House. It’s one thing to list them off, but another entirely when two or three competing effects appear at the same time. There’s a handy flowchart for each player, but, one, I’m apprehensive of any game that needs a flowchart, and two, usually those games are a lot bigger than a twenty-minute trick-taker. More than one of our early sessions fell to pieces under the load of all those special rules.

Complicating matters further, Man-Eating House plays rather differently depending on player count. The weaker mode is with three players, although on paper the idea sounds cool. The gist is that it’s two-versus-one, but nobody knows for sure who’s on whose side. As the game progresses, whomever plays the Old Man becomes a team of one, working to capture enough kids and ghosts to overwhelm the others. Thanks to the appearance of up to three creepy little girls, the Old Man might pass around the table multiple times before the teams are actually set. It’s a neat idea, but also a little too cluttered for my liking.

The four player mode, on the other hand, is slick. This forms players into two partnerships, which allows quite a bit of latitude in how tricks come together. Both teams are both proactive and reactive, bidding cards and potentially responding to all those special plays. Because tricks are more dynamic than usual, with some cards disappearing entirely thanks to escaping kids or slain ghosts, there’s a sense of escalation to each play. Where most trick-takers focus their drama on the resolution, tricks in Man-Eating House feel like they resolve multiple times. Having only three suits aids this sensation. It’s rare for a player to shed an entire suit early on. Even if they do, high numbers are more powerful regardless of suit, keeping everyone in the hand no matter what.

In the meantime, a few small touches go a long way toward ensuring that Man-Eating House stays fresh until the very end. For example, leftover cards are piled to the side as the “unopened room.” These are awarded to whomever wins the final trick. This prevents the last few plays from feeling perfunctory and adds a measure of uncertainty. Because the unopened room might contain additional kids or ghosts, a lot can hang on that last play. Or maybe you’ll swing the door open to reveal nothing. Man-Eating House isn’t scary — board games aren’t the right medium for that — but it understands the value of suspense.

This all adds up to quite the sum. Man-Eating House is a cryptid, all right, if only because it’s hard to take a clear picture of the thing. It’s too tangled for its own good, especially given how quick a session is. An entire game consists of one hand, leaving very little margin for error. As I noted earlier, our first couple of plays were pretty much a wash. We were checking the rules constantly, quibbling over order of operations, even checking the flowchart. Brrrr.

But it does come together, eventually. When it does, this is a rewarding and weird trick-taker, rather unlike anything else out there thanks to some clever design choices that can easily go overlooked. It still isn’t my favorite example of the genre, but I’d be happy to lend it a few more hands. Hopefully it’ll give them back when it’s done.

Man-Eating House goes up for preorder at New Mill Industries on October 1st.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on September 17, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Man-Eating House, New Mill Industries. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

Thank you for this review! I love when a game is willing to commit to the weird. The overall vibe reminds me of the film House (1977), though its influences probably flow from a dozen other sources less-known in the states.

Happy to do it! I forgot to include that preorders will go live on the New Mill Industries site on October 1st. I added the link to the review.

Yessss, Hausu came immediately to my mind, too! One of the weirdest movies I’ve ever seen.

Board games aren’t scary? Certainly there are games that cause me to feel dread or anxiety. Lord of the Rings the Confrontation. 6 nimmt!. For two examples. I admit their settings are not horror, but I still feel fear when I play them. I suppose the closest I find to fear with a horror setting is Ghost Stories with the White Moon expansion. I definitely worry about those family members. Twilight Struggle even, when I’m stuck with a defcon suicide card in hand with no way to get rid of it and it’s possible that I’ll draw another one in the next round. Which… is fitting for the setting. Although alt-history nuclear holocaust is likely not considered horror on its own.

I admit to being surprised that you would say that board games are not the right medium to produce fear. Am I just misunderstanding?

Personally, I think board games struggle to produce what we might call “active” emotions, because they never escape the reality that you are handling the arithmetic/engine under the hood. If the designer is the director, you are the actors within the film, not the viewers. But this isn’t a perfect analogy, because board games obviously can and do produce emotions! Also, metaphors are metaphors, not strict interpretations. It’s just that those emotions are regulated through the limitations and advantages of the medium, the same way film or literature or music or any other medium confers its own limitations and advantages.

In other words, board games often make me feel what I might call “competitive anxiety,” but I don’t think one has ever made me afraid the way a film or book has.

The fear I feel when playing a game is certainly distinct from that I might feel listening to music or watching a film, in that once I leave the magic circle, the fear also gets left behind (note, other emotions, such as anger or joy, or the shock I felt during a particular event from Pandemic Legacy (which led to the rest of that session being played in silence such was the impact on us), can last far beyond the confines of the magic circle). Mind, unlike you, I am less certain that I have ever even felt fear while reading a novel, let alone had it survive putting the book down (perhaps I felt fear when reading Room a novel). I certainly have no memories of the chills I felt for an hour after finishing Misery last night or that time I watched Saw by myself at midnight in my grandmother’s abandoned house and could not sleep for hours as I did not want to close my eyes and every creak of the wooden floors made me jump.

Mind, I often think of board games as being in their infancy as far as design goes. We seem to still be designing games for more or less the same reasons, with few games trying to craft a new type of experience.

I also think that discussing the emotional impact of board games during and after play is likely an enormous conversation that someone could likely devote an entire book to (or a website, if you will).

Pingback: Nightmare Jass | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Idle Tricks Are the Devil’s Game Table | SPACE-BIFF!