We Are All on Drugs

Everything I know about rock and roll, I learned from biopics. Now look, I’m a boring straight-edge, a real square, but watching Ray, Bohemian Rhapsody, Rocketman, Elvis, and Back to Black within the span of a year doesn’t give the, ah, healthiest impression of the career. So many young talents teetering on the brink of annihilation. Hopefully I’ve just missed all the wholesome ones.

Or maybe it’s that perpetual teetering that ignites our admiration. If nothing else, Rock Hard: 1977 feels primed to make such a statement. Playing this game is like riding a rocket ship on a gravity-breaking trajectory, albeit with an awareness that some seal or bolt has been improperly fitted and will vaporize upon contact with the upper atmosphere. As a worker-placement game, it’s merely okay. But as an accelerant-soaked wick leading not to a candle but to a firecracker, it hits many of the right notes.

One, two, one two three four.

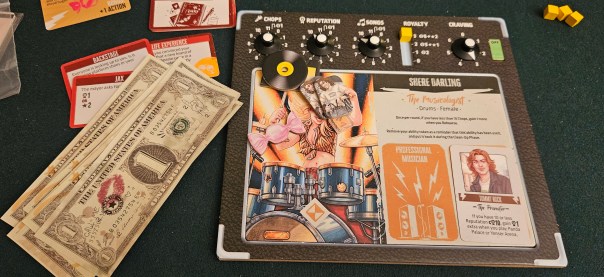

Rock Hard is arranged around the year in the life of a rising rock star. Nine months, really, but with the sense that the first quarter was spent laboring over a few songs, drilling sick riffs, and eking out a few bucks at dead-end jobs. There’s no scene where your character haltingly realizes they can strum out those first few evocative chords. All of that is handled during setup thanks to a pair of backstory cards, a selection of goals, a single dollar and a wad of candy. This is the almost not-famous stage of your career. One wrong turn and you’ll spend your life reading about other stars in the tabloids.

As a mechanical plaything, designed with ostensible virtues such as balance or competitiveness, the worker placement is, as I noted, merely okay, veering between workable and self-contradictory. The gist is that every month is broken into three phases representing an abstraction of how you spent that month’s days, evenings, and late nights. The board is divided into segments that represent these temporal slices, plus a selection that can be done pretty much any time you like. Mornings, for example, are when one interviews on radio shows, engages in shady promotion to get their songs on the airwaves, hires roadies, or dazzles record executives. Evenings are reserved for performances. Late night… well, you can always go to bed early to get a jump on the next day. Or you can bounce between hot destinations, moving movers and shaking shakers to hone your skills, inspire new songs, or, most importantly, pump up your fame.

Now here’s the paradox. The central weakness of Rock Hard is also its most appealing draw. In many cases, the very things that prevent it from being all that interesting as a worker-placement game are also what make it evocative of its time, place, and authorship. We could call it randomness, but it isn’t only that. True enough, Rock Hard is absolutely crammed with random factors. The outcome of all that late-night monkeying around, for instance. Each hotspot has its own deck of possibilities, some of which are more or less impactful than others. Where one visit could see a record exec stroking your ego for a single point of fame, another might let you play a gig the next day with an incomplete crew, license your songs out for Japanese beer jingles at the exact moment you need some scratch, or — depending on another layer of randomness — appeal to a local concert reviewer if you’re a woman.

This extends to everything within the game. Depending on a die roll, your job as a massage therapist might only result in some rather, ahem, late-night visits, gumming up your best barhopping hours. Random gigs might show up at precisely the opportune time for some stars but be worthless for others — not to mention, the humiliation of a serious band playing a bar mitzvah could produce long-term setbacks. More than once, we saw players select objectives at the start of the game that were utterly blocked thanks to an ill-timed event that shuttered the necessary venue. Sad trombone sound.

To be clear, these random occurrences are every bit as evocative as they are frustrating. To no small degree, they’re evocative because they’re frustrating. Within the game’s magic circle, this is a tale about some kid making it big despite any number of setbacks. That only makes sense if sometimes you fail your blood-sugar roll and wind up in rehab.

At the same time, Rock Hard never fully unites its bifurcated identities. Rather than running on vibes, this is also a game with varying victory point values and careful action chains and quirky synergies. It’s a game you can play well. Which raises questions about the little artificialities that we’re so accepting of as tabletop gamers, like victory-point races to be the first player to max out your chops dial (which, of course, goes to 11) or a hidden goal to perform at the Yenser Arena by September that can’t be adjusted when some rich asshole books the place for the whole month. As a study in how board games excel at modeling but fall flat on their faces the instant those models are challenged, there’s plenty to dig into here.

I also can’t help but wonder whether there was some studio-artist friction at play. Devir has made no bones about highlighting Rock Hard’s authorship in marketing materials, a smart move when your designer is Jackie Fox of The Runaways, someone who knows more than any of us about both the intoxication and pitfalls of underage fame. Thanks to Fox, every so often the game steers hard into oncoming traffic. Those are its best moments, little sparks of truthiness flung in the face of the game’s limitations.

The most obvious example is the candy. Turns in Rock Hard are strictly limited to a single action. So, to get ahead, you eat candy. This draws a card from the sugar rush deck, awarding an extra action for soft candy, two extra actions for hard candy, or maybe zero actions if your candy has been cut with aspirin — sorry, if your candy is sugar-free. The benefits are obvious, effectively doubling or even tripling how much you can get done. Sure, certain actions can’t be taken on candy. It’s impossible to hit the hay early under the effects of a sugar rush, or work properly, or even play most venues. But practicing at home? Writing songs with nonsensical lyrics? Curbing your anxiety about meeting with record execs? Those are activities best undertaken on as much candy as you can fit between your cheeks.

The tradeoff is that candy also necessitates a die roll to see whether your blood sugar has gotten out of control. In the game’s early stages, a sugar crash is rare. Later, as your candy use becomes more habitual, crashing is more common. This forces players to spend the next morning in recovery. Which, honestly, isn’t all that bad an outcome after nearly doubling how much you could get done last month. Still, an inopportune sugar coma can present a serious hurdle for any would-be rocker.

And, sure, it’s cute to phrase drugs as candy. But we all know it’s drugs, right? I know it’s drugs. You know it’s drugs. My ten-year-old knew it was drugs. In Rock Hard, we are all on drugs, we all know we’re all on drugs, so it’s not clear why we need this euphemism to hide behind. Gimme some of that stuff. Woo!

But this is what I mean when I say that Rock Hard doesn’t quite braid its identities together. In some instances, the game is darkly funny. “Who doesn’t love twins?” reads one of the cards you can draw when hanging backstage, a bright red lipstick stain indicating the card’s suit. Now that’s an implication, both amusing and sickly. But when it comes to the follow-through, Rock Hard pulls up short. We will merely comment on twins, not bed them. We will suck on candy, not Quaaludes. We will employ managers who keep siphoning away more and more of our hard-earned royalties, but not pressure us into a corner where we can’t say no.

To be clear, it isn’t that I want Rock Hard to be dour and unsmiling, and I sure as hell don’t want it to preach at me. Rather, it tries to walk in two directions at once, and in the process doesn’t step across the line either way, neither committing to its gaminess nor its expressionism. It’s sturdy enough as a points-optimizing worker-placement game, but is also riddled with evocative details and reverses of fortune that speak to the hard knocks that accompany fame. But as soon as it glances toward those hard knocks, it’s furtive and shy, even moralistic in what it refuses to reveal, in that particular corporate way that confuses portrayal for advocacy. If we admit that our characters only manage their stardom through copious drug use, then surely we are encouraging drugs. If we sleep with the twins, then we’re winking at incest. If we don’t touch upon the complicated power our manager wields over us, then we don’t risk offending the “games should just be games” dorks by becoming too #MeToo about it. Every time Rock Hard edges toward a conclusive statement, it prevaricates.

Look, I don’t mean to make Rock Hard the flashpoint here. The culture of tabletop games has put itself in a tight spot. In the same breath we’ll say that games are art while also flinching away from honest or difficult depictions of human behavior. Where other mediums have carved out the space to clarify their relationship to artifice and their inbuilt limitations, board games are stuck in an ever-mutating apologia. A commercial release like Rock Hard can’t contain hard drugs or sex pest managers because, well, because they can’t. What remains is the glamor. A hard-bitten glamor, glamor with setbacks, but glamor without the price of immortality ever coming due.

The irony is that these efforts are doomed to failure. As one friend recounted it, his first session with Rock Hard was prefaced by the teacher’s disclaimer that the game contained “adult material.” The material in question? That some of the characters are labeled “androgynous” while others are defined as male or female. Even with the offensive edges sanded down, the mere existence of the game’s protagonists is enough to rile up some folks. Peddling to everyone means peddling to no one in particular.

Despite all of that, I will admit I’ve enjoyed my time with Rock Hard. It was a complicated enjoyment, to be sure, but it does enough things well that I came away glad to have tried it, even if it proved more polarizing than most of the titles that hit my table. The paper money feels good, its unnamed city produces a lively setting, and its “year in the life” framing puts it on firmer footing than most worker-placement games. Perhaps most of all, it provides that vicarious thrill of quitting your shit job, tossing back handfuls of candy, and becoming a rock god. If it comes short.. well, again, it hits most of the right notes. But if there’s anything I’ve learned from my two attempts at Guitar Hero, it’s that most isn’t always good enough.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

Posted on September 11, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Devir, Rock Hard: 1977. Bookmark the permalink. 12 Comments.

We have played the crap outta this game with many folks, and it is always a good time. Very approachable for new players, and it can be wildly hilarious with the right group. Love it!

It definitely hits those high notes! Glad to hear you’re enjoying it so much.

This hits the spot for how my group has found Rock Hard 1977. It’s an alright game, but we didn’t just want an alright game. We bought it because it was designed by Jackie Fucking Fox. I guess I was hoping for something more direct.

Sorry to hear it hasn’t landed for you.

I don’t think that it takes corporate interference for a successful rock musician to not depict the rock world as misery porn. Jackie Fox did *win* the real world game of Rock Hard after all.

Hell of a thing to say when she was raped by her manager, mate.

I… did not know that. Fuck.

[comment moderated: Let’s not do pile-ons here, please.]

I wonder how much of the watering down was trying not to have any spillover effect of bad publicity/morally-crusading busybodies impacting Devir’s other games that aren’t courting controversy so easily

Also, if you want a great rock story, it’s a book rather than a biopic, go get Steven Taylor’s (“Taylor” not “Tyler”) autobiography of his time on the road with The Uninvited. It’s easily one of the most readable/enjoyable rock books, and I thought it was waaaay better than Dave Grohl’s book.

(https://www.amazon.com/Uninvited-Steven-Vance-Taylor/dp/0578367815)

Thanks for the recommendation!

I don’t want to speculate too much about any possible give and take between Fox and Devir, but it’s hard to imagine a publisher like them tackling certain topics too directly. If anything, I’m impressed by how much Fox was able to insert into the design! I sincerely hope that everybody involved is happy with how it turned out.

Thanks for the interesting thoughts. I feel like there could be a long form essay on how the medium seems perpetually caught in headlights of clean inoffensivity, with only enough wiggle room to offend.

With that it is quite clear that the game does well to even wink at the darker topic on the sidelines. In all I think Devir are quite brave for even allowing such obvious sleights of hand. Normally when we all know, that is the point at which something is scrubbed or cleaned for the family table.

Pingback: Almost Famous | SPACE-BIFF!