Infinite Gest

One of my professors believed that every generation needed to retell the story of Julius Caesar. In her mind, the story functioned as a sort of cultural tonic. Tyrant or hero, victim or opportunist — Caesar was a lens through which generations current and future might better witness themselves.

In playing Fred Serval’s A Gest of Robin Rood, the second installment in the Irregular Conflicts Series, itself a spinoff of the long-running COIN Series, the same could be said of everybody’s favorite forest fox. Is he a vagabond, robbing the rich for no other reason than because their wealth is there for the taking? Is he a lower-class hero, uplifting the poor? Has he been coopted by the gentlefolk, elevated to a lordling deprived of his privileges? Is he a crusader? A jokester? A kingsman? Does he venerate the Virgin Mary or has Maid Marian been invented to take her place? Eventually he’ll move into his gritty teenage years and relitigate the Battle of Normandy. Shhh. He gets embarrassed when we talk about that.

Serval’s approach to Robin Hood resembles an archaeological cross-section, descending through modern asphalt to carriage turnpikes, medieval trackways, and Roman roads. Rather than setting sights on a single era, he draws from a wellspring of sources. Where one event card sees Robin contending with venomous traitors or attending an archery contest in a cunning disguise — a colorful hood! — the next action sees him shaking down wayward monks or transforming into a twelfth-century guerrilla. This is Robin Hood in all his forms, a superposition of bandit and liberator and trickster and everything in between.

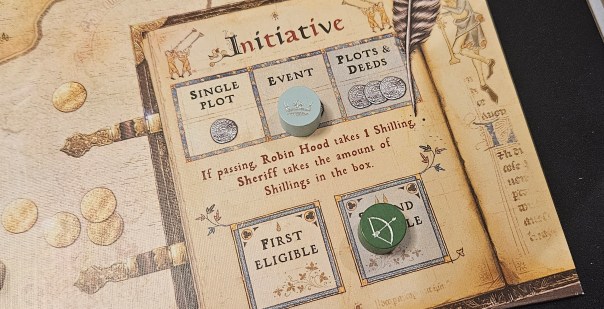

Foremost among those identities is the game’s location in the COIN Series. It’s a mouthful that defies digestion, staying on the plate while the others go down. In a year dominated by easy access points to Volko Ruhnke’s now-storied system, with People Power and The British Way and Vijayanagara already on the line, A Gest for Robin Hood offers the gentlest entry of them all. Everything has been streamlined to a fine surface. The artwork is inviting. The operations and special activities, dubbed “plots” and “deeds,” have been trimmed. The duration is around forty-five minutes rather than two to five hours. The deck has been tightened so that every card matters. The rulebook… well, the rulebook is still written in GMT’s signature style, with all the verve of a furniture assembly manual. But there’s a learn-to-play booklet that walks players through a full ballad, the game’s epithet for a round, and the diminished complexity goes a long way toward defanging the usual bite of learning one of these things.

Still, it’s a mixed bag. On the one hand, folktale provides a softer landing pad for those who’ve regarded the COIN Series curiously from the outside, wary of its political overtones or itemized rulebooks or relative complexity. On the other, the system that has defined a dozen other titles is like the abyss — peered into, it peers back.

As in the rest of the series, this is a system that centers procedure over all else. Ruhnke’s inaugural title, Andean Abyss, reads like an insider’s gamification of serious counterinsurgency operations, probably because that’s precisely what it is. Although the series has wandered afield, producing some of its finest volumes as it edges farther from those initial overtures at war simulation, its roots have never quite withered.

Here’s what I mean. When you think of Robin Hood, what springs to mind? There’s a good chance your intuition is included somewhere in Serval’s portrayal. This is a Robin Hood who indeed robs from the rich to give to the poor. He lurks in the relative security of the Sherwood Forest, ambushes passing carriages laden with gold, and gallivants from one side of the shire to the other.

But the way those activities are expressed swings us back to series hallmarks. What does it mean to rob from the rich? It means rolling a die against the Sheriff of Nottingham’s defenses. What about giving to the poor? For that, the old support/opposition system that dominates most COIN volumes rears its stately head. The Sheriff sticks to the same basics that governed previous entries, functioning like a downscaled Colombia, Batista, Afghanistan, ARVN. To secure the submission of his subjects, he must show force. To keep his coffers healthy, he must extract taxes. His nose is buried in a hearts-and-minds textbook.

Along the way, Serval produces a thesis about state formation, about the proximity and distinctions between bandits and enforcers, about the ideological clash between rural foquismo and a more urban approach to insurgency. Along the way, he embraces a playfulness not often seen in this sort of game. The playbook includes instructions for a tarot spread using the event cards revealed in each ballad. It’s gripping stuff!

But it’s also more textual than ludic. The best portions of A Gest of Robin Hood deal with questions of logistics and theft. When the Sheriff hopes to raise funds, he squeezes his parishes to produce carriages, economic hot-spots that trundle from the corners of the shire to Nottingham. There they will be converted into shillings and order, the Sheriff’s side of his tug-of-war with Robin Hood. If Robin happens to have Merry Men positioned along the way, especially in the crucial wooded periphery of Nottingham, he can interrupt their passage for some good old-fashioned highway robbery.

This isn’t the only object of Robin Hood’s antics. When there are no carriages about, he can also rob from a deck of victims. There’s a minor degree of customization afoot. Certain events add high-value targets to the deck — or, in the Sheriff’s case, add patrolling knights to disrupt the Merry Men. Meanwhile, Robin can choose whether to merely fleece his quarry or steal every farthing and even murder the poor sods. There are potential long-term ramifications for such brutality, blurring the lines between fanciful folktale and outright banditry.

Whatever his target, Robin’s success hinges on the roll of a die. Often, a flubbed roll presents a serious setback. The Sheriff can also play a shell-game, employing carriages loaded with extra guards. At every point, Robin must exhibit supreme caution, keeping the titular hero concealed among his Merry Men. Both sides thus get a chance to play at deception.

Curiously, the Sheriff never rolls a die. His operations — pardon me, plots — proceed with all the assuredness of a twentieth-century nation-state. As in previous COIN volumes, which portray insurgent activities as inherently testy but state activities as guaranteed in their outcome (provided they operate with sufficient resources and support), this delineation between Sheriff and Robin Hood is a peculiar one. The same goes for their relative mobility. The Sheriff’s men can gallop across the map in a heartbeat, but Robin slinks hither and yon. Certain events allude to his band’s ability to travel freely, using boats to move along rivers or the like, but on the whole his movements are restricted compared to those of the Sheriff.

These details feel like remnant assumptions, hangnails that were never trimmed from previous volumes. In, say, Cuba Libre or Andean Abyss, the government traveled freely because it had access to boats and helicopters. Here, contained within such a limited geography, Robin’s pokiness strikes the ear amiss.

These are small but instructive concerns. Put bluntly, Robin Hood is the more thrilling of the game’s factions — but he’s also trickier to play well. Perhaps that’s suitable, given their contrasting roles. Perhaps. But it’s also a source of some frustration. An aggressive Sheriff can corner Robin a little too easily, can make missteps, can suffer a string of poor events, and recover. Robin Hood must walk a tightrope at all times. Taking losses, especially those that imprison the Merry Men or Robin himself, can prove disastrous. Being eliminated from a particular theater, especially those isolated by the shire’s rivers, also strikes a significant blow.

I’m always wary of putting too much stock in balance. I have no doubt that some players will have inverse experiences to those that marked my sessions. Rather, my concerns have more to do with mouthfeel. A Gest of Robin Hood is chock-full of exciting morsels. Robbing a carriage. Turning a region against the Sheriff. Creeping into Nottingham to crack the treasury. One event lets a parish weaponize work stoppages and “peasant ignorance” to effectively opt them out of the game. Wonderful! What a perfect expression of the ways oppressed groups have historically warred with their overlords!

But while I’ve had a terrific time with certain aspects of A Gest of Robin Hood, I’ve also balked at its gristle. Invariably, these are the spots where it applies the COIN formula most stringently. The finicky procedures. Tallying patrols. Parishes teeter-tottering between submission and revolt. The royal checklist at the conclusion of each ballad. The best parts of this game are tethered to the earth by COIN procedures, not lifted skyward by them.

In a way, its dual identity only deepens Serval’s thesis. Because A Gest of Robin Hood is as much a reflection of its author’s perspective as any other retelling of the bandit’s legend. Some Robin Hoods are dashing. Some are daring. Some are silly, irreverent, iconoclastic, holy. Some are gritty. Brrr. Let’s not talk about those ones.

This Robin Hood is procedural. He selects his activities from a dual-layer menu, melting into Sherwood Forest, but only after taking his principal action and never before. This Robin Hood is actuarial. He counts shillings to determine if he has enough funding to bribe a henchman into joining his band. This Robin Hood is Che Guevara. He is a folktale grasping at the roots of his own legend.

And that makes A Gest for Robin Hood a jest indeed. As an entry point to the COIN Series, it’s considerable. I find myself wishing it had been an entry point to something else instead.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on July 12, 2024, in Board Game and tagged A Gest of Robin Hood, Board Games, COIN Series, Fred Serval, GMT Games. Bookmark the permalink. 12 Comments.

Like you, I have been thoroughly impressed by Vijayanagara, People Power and British Way. It sounds like this entry doesn’t quite live up to those precedents. In any case, I can’t imagine a way to play this one solo, so unfortunately that puts it off the table for me.

I think the recent rush of very good COIN titles is part of my dissatisfaction. I wish this game had handled its combat as cleverly as Vijayanagara or been as streamlined as The British Way.

Sadly, there is no solo mode. Fred explains why in the rulebook (playbook? not sure which), but solitaire is how a number of folks play these things.

I always appreciate your reviews Dan, specifically that you take care to paint a full picture of your experience, including things to appreciate when you are feeling lukewarm or dissatisfied with a game.

This game is at the top of my “might get to play soon” list. While I would have obviously preferred that the game left you gushing, it also sounds like the game will be a good fit for me and my potential opponent, whose combined COIN experience is zero, hahaha!

It’s a distinct possibility! I think I have some COIN fatigue, despite appreciating the system quite a bit.

Thanks for the great review, I feel your criticisms are very on point. I enjoyed the game a lot personally, mostly because I am having a lot of fun introducing friends to COIN with this game. It’s a less grim topic and an easier entry point to COIN, and this has allowed me to play with loved ones that would not touch Fire in the Lake with a ten pole stick. I think the game is in fact more complex than The British Way, but the topic is just so much more accessible to most around me (the art helps a lot too).

I am very thankful that the irregular conflict series is slowly widening the possibilities of COIN. But you can feel the tentativeness of the transition in this game. A couple of things bothered me thematically: the idea of big operation that is so central to COIN seems a bit anachronistic in this setting, and a recurrent rules confusion I observed is that players don’t understand the logic of “one plot in up to 3 spaces”, and would intuitively perform different plots in each space, or e.g. perform the same plot twice in the same space during an action. I guess what I am saying is that as an introduction to COIN, the theme does not always align with the “COIN logic” that is second nature to series players.

I love this game, but I might be the best target audience for it: a COIN enthusiast that wants to introduce the system to friends and family, who are usually averse to difficult historical topics and long procedural games. The procedure is still there, and a bit anti-thematic, but in a short and beautiful game, and without having to deal with grim historical topics.

Good thoughts, fedebenitez! I’m glad to hear it’s working for you. Since I already have plenty of COIN players in my midst, I don’t have much need to lure them in with a softer topic. That’s definitely a huge draw.

TV critic AA Gill once wrote that every generation gets the Robin Hood it deserves (Jason Connery as a new age-y pagan in the 80s; the BBC’s 2010s series as Robin Hood with an ASBO, and so on).

Thanks for the review. I bounced off Red Flag Over Paris. I love the idea of the Merry Men as an insurgency, but still not sure about the COIN system. One to ponder on – your comments certainly give food for thought.

My, but it’s a pretty game though!

I do love how it looks.

I loved this game when I first started playing it, but there was one game in particular that soured me on it tremendously.

I play the Sheriff and my partner plays RH – usually I take the win but our games were somewhat close in the beginning. About our 12th game we play, I shit you not, throughout the entirety of the game she never rolled a -1 on the green die face, resulting in her never failing a rob roll. She rolled something like 3/3/1/2/0/3/1/2/3, having infinite money to recruit, donate, and sneak to her heart’s content to win easily.

The backbreaker was when I decided to send 2 trap carriages to Nottingham, even accompanied them with Henchmen, and STILL lost both to +2/+3 Robs.

There was no counterplay whatsoever to such luck. And it’s not remotely thematic to Robin Hood, either – it’s not “clever” to roll in such a way, it’s just lucky. Similarly, when I would play RH and just get -1/-1/-1/0/-1/1/1/0/-1 through the game, I could do next to nothing and it was a guaranteed loss.

It’s a bizarre balance where Robin Hood is clearly the stronger faction, by a long shot, but only if the dice play out that way. I just feel somewhat ‘tricked,’ I guess – this game was my second foray into the COIN system and I was expecting far less RNG to it. Root was my first and sure, there’s a little dice rolling here and there, but it is way more strategic. Went from feeling Gest as a 9 and it feels more like a 7.5 after 15ish games.

Cheers to your review!

Pingback: 5 on Friday 19/07/24 – No Rerolls

Pingback: Non Eventu | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: A Gest of Robin Hood Board Game Review - Bumbling Through Dungeons