Stand Up by Sitting Down!

We all feel it. Told to work faster, work harder, produce more, keep that line flying till it’s near vertical. Shown the lives we could lead if we earned enough, big houses that overlook smaller houses, seats at the foot of the owner’s table, whining for scraps. Threatened with losing everything — our roofs, our kids, our health — if we don’t keep our heads down and play along.

In 1934, the CEO of General Motors, Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., took home one hundred times the average American wage. That’s one of many tidbits written into the margins of Striking Flint, John du Bois’s latest title and spiritual partner to Heading Forward. Like that earlier game, which pitted the player’s recovery from a traumatic brain injury against the deadlines of a health insurance company, Striking Flint offers an empathetic glimpse into an overlooked reality of American livelihood. It begins with the 1936-7 General Motors sit-down strike of Flint, Michigan.

We could list the reasons why the United Automobile Workers, formed only a year before the strike began, felt it necessary to authorize the workers of Flint to sit down at their stations and thus occupy the essential factories for producing General Motors’ Pontiacs, Buicks, and Oldsmobiles, but those reasons would seem all too pedestrian. The short version is that automotive workers were being told to do more with less, work harder and longer shifts for slighter take-home pay, and watch as handfuls of their coworkers were fired and their positions never refilled. Sound familiar?

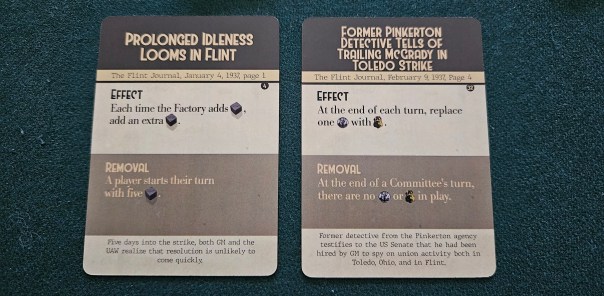

In du Bois’s depiction, Striking Flint operates like a reverse worker-placement game. The factories and streets are represented as action spaces, each printed with their own outcome that will trigger at regular intervals. There are only a handful of possibilities, but each poses a clear threat to your strike. Some exhaust your workers, piling on stress and hunger and the long hours and days of sitting at their posts. Others remove your workers outright. The most persistent and interesting spaces add strikebreakers, little tokens that stick around and threaten to dislodge your workers by hook or by crook. There are three types: money draws your people toward them like sirens, promising to end their suffering for a pittance, while scabs drive them out of secure positions and police hound them directly, chasing them onto the factory floor and beating them off the board.

Here’s the good news: by occupying those spaces, you can prevent them from triggering. You’ll never have enough manpower to block everything, so this process is necessarily strategic. It’s always useful to negate the spaces that directly remove workers, for instance. Depending on any current event, it might also be useful to smother any spaces that allow General Motors to offer cash to your workers, or deploy more police, or make conditions for the strikers more fatiguing. Sometimes, you’ll be too harried to play so cautiously. It’s all you can do to keep your pieces on the board and in the factories.

It’s a clever system, one that works well not only because it’s readable and offers clear import, but also because of how naturally it slots into our hobby’s history. As a genre, worker placement has long been due either an adjustment or a reckoning, a corrective to remind us that not all workers appreciate being treated as replaceable cogs. Some games have moved in this direction, portraying workers that need to be fed or that tire when used too often. But this is one of the few games out there, maybe the only game, that actually centers the workers and their needs, the abuses that have driven them to collective action, and the possibility of fulfilling the former and easing the latter. At all moments, their function is clear: these workers are in the business of stopping anything from happening. For a time, anyway.

Everyone’s shared goal is to force General Motors to the negotiating table. This is complicated by the factory’s periodic resistance to your efforts. As your committees take more actions, they consume more time on the in-game calendar. Inevitably, this triggers those dreaded rolls to see how the company has decided to fight back. Every turn that ends with the workers in control of two factories — filled with their pieces and no strikebreakers — the company ticks one slot closer to making a deal with the union.

This sometimes leads to moments of gaminess. For example, if your turn seeks to conclude under the proper circumstances, you might juggle your actions to effectively press the company two spaces toward a deal instead of only one. While these moments are obviously abstracted, they’re abstract in a way reminiscent of old call-to-action games like Suffragetto. Striking Flint feels like a game out of time, one foot planted in the past as an artifact that striking workers might have played while passing the hours or that unions might have printed to get the word out, and the other foot in the present to make up the difference in what we’ve come to expect from modern gameplay.

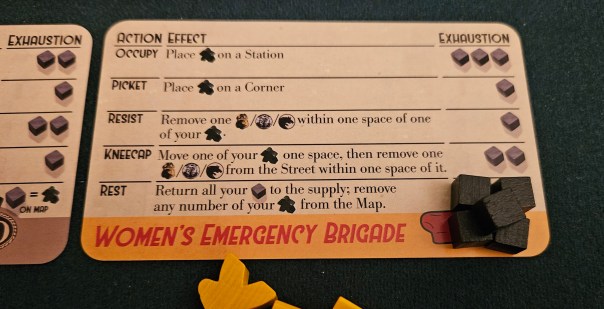

Foremost among those modern developments is the individual personality of your committees. There are five in all, each representing a different group of strikers that sat down for their rights, along with a few key distinctions that endow them with a sense of purpose and identity. Where rank-and-file workers have easy access to the factory floor and can sneak their fellows in through the back door, the broader Congress of Industrial Organizations lacks local contacts but excels at organization. The socialists are zealous and can whip their fellow committees into a frenzy, but have a serious public image problem and don’t fare well on the streets. The United War Veterans of Flint are easily fatigued but scrappy in a fight — and it will come to that, as in the historical strike’s “Battle of Running Bulls,” in which fourteen strikers were injured by gunfire but still managed to beat back a police assault by pelting them with hinges and bolts. My personal favorite committee, the Women’s Emergency Brigade, is unlikely to occupy any factories, but by dint of their sex can become a public relations nightmare when attacked by the police, transforming them into ideal front-line picketers that can push back all manner of strikebreakers. Everybody plays a role.

One crucial takeaway from these committees is their wide-ranging nature. These were people with different outlooks who came together for the benefit of all. Alex Knight’s Land and Freedom did something similar last year, digging into the distinctions between the socialist factions that briefly constituted the Second Spanish Republic. But where Land and Freedom emphasized the rifts that drove those factions apart and permitted the dissolution of the Republic, Striking Flint is more optimistic. Despite every opposition — the police, the Pinkertons, the libelous efforts of the company-slanted local newspaper — the strike succeeded. After forty-four days, General Motors was forced to the table.

This is perhaps where Striking Flint bears its closest resemblance to Heading Forward while still carving out its own statement. These are both games about the abuses people weather when trapped in systems that regard them as little more than variables in money-accruing engines. Just as the unnamed protagonist of Heading Forward was pressured to meet proscribed recovery benchmarks in an effort to appease their insurance provider, so too have the workers of Striking Flint been put through their paces by a company that has blinded itself to their needs. The difference is one of volume: Heading Forward is about an individual, Striking Flint is about many individuals working together. When the company sends in the police to beat workers and picketers, that detail is never far from mind. When the Flint Journal levies false accusations against your pieces, it’s hard not to feel some spark of righteous anger.

And when your committee stands alongside its fellows, people with their own opinions and grievances, but alike in the belief that a person should receive a fair wage, the game becomes something more.

To be clear, Striking Flint also works as a plaything, especially once the difficulty has been cranked up for maximum resentment. Its baseline form is perhaps too simple; we could usually win without resorting to anything too clever. But in the proper configurations — the tougher calendar, an extra factory tile, two or more events to contend with at once — it becomes a pressure cooker of labor radicalization. It serves as a reminder that many of the labor rights we appreciate today are the direct result of somebody, many somebodies, putting their livelihoods and safety on the line.

It’s also a reminder that labor rights have been steadily eroded. Today, Mary Barra, the CEO of General Motors, earns over four hundred times the average American wage. As with Heading Forward, du Bois has once again crafted a game that’s as much a call to empathy and a call to action as it is an experience that unfurls on the table.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on June 17, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Hollandspiele, Striking Flint. Bookmark the permalink. 5 Comments.

Why I oughtta…! *shakes fist*

Wait, never mind!

=O

Pingback: Those Dying Generations at Their Song | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Space-Cast! #40. Heading Flint | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Ode to the Depot | SPACE-BIFF!