Last of the Loner Romans

Poor Rome. No matter how many centuries fly by, her problems remain the same. When last we spied the immortal city — or at least the version found in Robert DeLeskie’s solo wargame Wars of Marcus Aurelius — the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Iazyges were harassing the frontiers. Now it’s the Goths, Vandals, and an upstart general named Constantine III who’s decided he’d rather call the shots for a change. Thank goodness for loyal half-barbarian Stilicho, ready to defend the young Emperor Honorius from all comers.

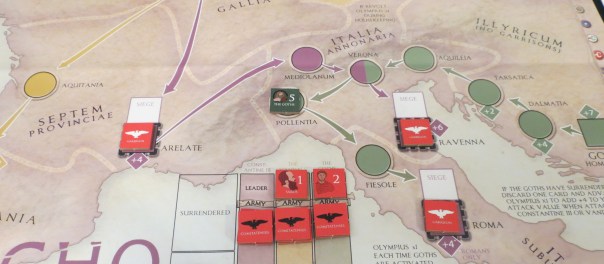

At a glance, not much has changed, either in Rome’s last two and a half centuries or between DeLeskie’s previous game and Stilicho: Last of the Romans. For the uninitiated, you’ve likely seen those maps that chart the barbarian incursions into Roman territory. You’ve got a tangle of arrows representing the various Goths, a trio for the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons, an itty-bitty diaspora of Franks, the continent-circling fishhook of the Vandals, all chased by a tidal wave of Huns. Let’s set aside this map’s historicity, its abstraction, its complicated centuries of settlement and alliance and disagreement with Rome, even Stilicho’s heritage as the son of a Vandal. That map is properly simplified down to three tracks meant to capture a single flashpoint when the Empire’s demise was all but assured. Enemy forces march toward your heartlands, lay siege to your garrisons, and are often repelled across lengthy campaigns. Your forces wax and wane. Dice are cast.

For anyone involved with mid-weight wargames, this proximity to the States of Siege genre is so familiar that it’s practically comfort food. Stilicho — the game, not the general — leans into this familiarity. Where Wars of Marcus Aurelius was cramped, Stilicho stretches out a bit. There’s room enough for every token, and hardly ever reason to stack one atop the other. If anything, the tokens are diminutive alongside the sprawl of the continent. When an army of Vandals grows feisty, they aren’t inching from one hedgerow to another. They’re pillaging the Tour de France. The same goes for Constantine III and the Goths. The dominoes took decades to properly set up, all the effort in the Empire invested into sorting and keeping them in tidy rows. Now is the moment when they finally topple.

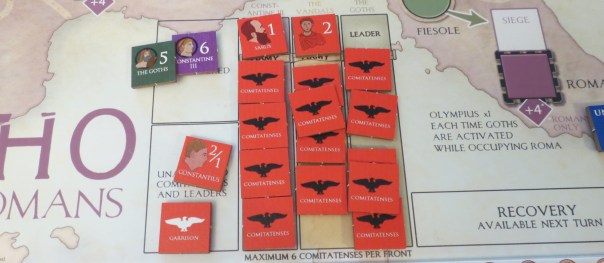

If Stilicho is familiar in its setting of decline and its broad format, its cards are both where it’s most recognizable but also most apt to show some glimmer of novelty. This, too, is reminiscent of Wars of Marcus Aurelius, but don’t go labeling DeLeskie a one-tactic cavalry officer just yet. As in DeLeskie’s previous game, Stilicho and his rivals are governed by two decks of cards. The enemies of Rome draw three at a time, triggering intrigues or mutinies or outright invasions, followed by Stilicho drawing five, three, or one card depending on the season. This naturally gives rise to moments of plenty and stretches of famine, tasking the general with Rome’s defense with only a small selection of historical events — or actions taken at your own discretion, if you’d rather discard a card rather than utilize its event. At this point, the choice between an event or an action point is so ubiquitous that it almost doesn’t warrant mention.

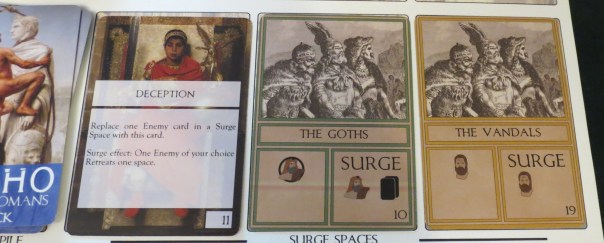

What does warrant mention is the way your enemies gather their strength. Each enemy card reveals some scheme, often an invasion, and hopefully one that rebounds fruitlessly from one of your garrisons. But these are mere rumbles from the horizon. As soon as three invasions accumulate, the cards trigger again with redoubled momentum. Now your foes take yet another action, sometimes two, sometimes pillaging or returning to their deck for another bout.

Again, this is nearly a copy of the system DeLeskie leveraged before. But DeLeskie’s strength this time around lies in refinement, and these surges of barbarian zeal are more interesting to counter. For one thing, the cards in your hand are often useful as insurance. In addition to being able to block individual surging cards altogether, an investment best reserved for when Constantine III’s traitorous army invades multiple territories at once, cards are also useful in battle. Each discard increases the result of your roll, potentially swinging a disaster into a victory. Even cooler, certain events can replace enemy cards in the timeline, lying in wait until a surge triggers their ability.

These are both significant improvements. Where Wars of Marcus Aurelius often came across as fickle, Stilicho provides much-needed tools of disruption. Battles are still dicey affairs, but there’s more of a sense that you’re preparing for a fight by grooming your hand. Failed rolls are more than the outcome of chance; they’re decisions of logistics and hand management. As such, many of the game’s decisions are sharper, sounder, and more legible. Should you spend two cards to win this fight when you can try again for only one? Should you attack those barbarians now, or wait until you have extra cards to spend? If you wait, will the enemy slip back into the position you only recently dislodged them from? Should you attack Constantine III, or let him sit in the path of the Vandals in the hopes that they come to blows later? Which cards should you reserve between seasons, and which between years? Remember, the occasional event may force a discard. With that in mind, should you spend everything now, or hope you draw the right cards to mount a successful invasion of enemy country next year? As soon as they’re crushed, you can levy the survivors into fighting alongside you. Apart from the rumblings at home, there’s barely anything to worry about, right?

The beauty of DeLeskie’s design is that these decisions are almost naturalistic, less obsessed with procedure and more interested in the sorts of conundrums a commander-in-chief would face when marshaling a waning empire’s forces. It’s easy to envision the trade-off of campaigning now while your rivals are demoralized or later after your soldiers are resupplied, of halting a campaign because you’ve maneuvered one enemy into the path of another, of being forced to return home to rebut rumors of your incompetence or put down yet another rebellion. There are fires aplenty to douse, yet you only have so many buckets of sand.

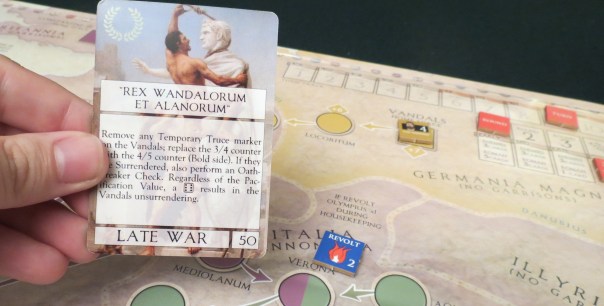

This isn’t to say the decision space is too broad. Nor is it to say there aren’t hiccups. In the first case, Stilicho is admirably restrained, both in its rules and in its scope. The introduction warns that the historical Stilicho — the man, not the game — lost his head on turn three. The hypothetical, still-membered Stilicho can stick around for many years after 408 CE, but his work remains focused: pressuring all three invaders into surrender while keeping his head on his shoulders and the Empire more or less intact. A few late-war cards are eventually added to the deck to keep things spicy, but the game sticks to its course as staidly as the Vandals and Goths follow their respective arrows.

As for hiccups, the good news is that Stilicho is a genuine improvement in nearly every regard. The difficulty is still out of whack — its challenges are too easily surmounted this time — and after a couple of plays it grows exhausting how often your enemies seesaw back and forth as though they were knitted of rubber rather than blood and bone. The worst offender is its stack of generic cards, effectively blanks that can only be spent for an action rather than used for an event. These didn’t need to be fancy, but simply labeling them “ACTION CARD” draws attention to the gaminess of the whole thing, rather than embracing the aforementioned naturalism of the setting.

But as I said, these are hiccups. For the most part, Stilicho is fixating rather than revolutionary. Its struggle is focused with all the intensity of its protagonist, communicating a fragment of Stilicho’s struggle against multiple invasions with great clarity. There’s nothing quite as satisfying as rallying former enemies against the final bastion of your last foe, especially when a string of victories have silenced your opposition back home. This is the advantage of fine-tuning a system rather than turning it over entirely; at last the rules are allowed to step out of the way and let us get down to the business of sampling history.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on September 7, 2020, in Board Game and tagged Alone Time, Board Games, Hollandspiele, Stilicho: Last of the Romans. Bookmark the permalink. 9 Comments.

Hello. Which states of siege game is considered the best? I have a limited room space and outh to get only one gme. Is Stilicho it or is Something else from this series better?

Thank you for any answer.

Nejc

Great question, Nejc! I’d recommend picking the topic that appeals to you. Most States of Siege games are historical. Some of my favorites include Stilicho, The First Jihad (quite heavy), and Dawn of the Zeds. That last obviously one isn’t about history, but it’s probably the most polished and least wargamey of the bunch.

Stilicho it is for me then.

Thank you.

Stilicho ordered from the Second Chance Games today. Thank you again for your part in me ordering and looking forward to your future solo games reviews. 🙂

Enjoy, Nejc!

I’m just now familiarizing myself with Hollandspiele, based on your very recent article on the freebie games. I’m very much interested in this and its predecessor. Sounds like this is an overall improvement; is the first one worth getting in your estimation? Assuming for a moment, hypothetically, that time, money, and space for games is finite, would you get both, the first, it this one?

I would go with this one, personally.

Pingback: Review: Stilicho: Last of the Romans:: Last of the Loner Romans (a Space-Biff! review) – Indie Games Only

Pingback: When Fire Met Stone | SPACE-BIFF!