A Prickle of Trickers

Say it with me now: All I play anymore is trick-taking games.

Every so often, one comes along that makes me perk up and take note. Which is an exciting (if unfair) way of setting these three Indie Games Night Market games against one another. Three trickers enter. All three leave. But one of them leaves with its head held a little higher than the others.

Venusian Vegas

First in this trio of high-concept trick-takers is Venusian Vegas by Chris Prime. In the far future, humanity has established a floating colony on our system’s terrestrial pressure cooker. Except this is a “grim darkness” type of far future, because our city in the sulfuric clouds isn’t there for research or sustainable living or mankind’s first real attempt at egalitarianism.

Oh no. It’s a casino.

This does tinge the ensuing activities with some degree of righteousness. Because we aren’t here to feed our life’s savings into a slot machine. We’re here to heist this bastard.

Of today’s trick-takers, Venusian Vegas is the most straightforward. This doesn’t make it ordinary, instead splitting it between one half tricker, another half engine-builder. Winning tricks allows the victor to pick a reward from the cards played to the table. Their opponents’ cards, giving the game a shade of social preemption as players decline to put out offerings that will prove too beneficial. Some cards award points, but others level up your standing on five tracks.

This, by the way, is where Venusian Vegas stands up on a stool and makes itself known. Those tracks are the engine under the hood. They’re also little cheats. The first track increases your hand size. An enormous boon, not only because it gives you more cards to play with, but because when the round concludes any leftovers still in your hand provide additional bonuses. Of the five options, this is the track most traveled. And for good reason.

But the others offer noteworthy incentives of their own, each in the form of spendable tokens — nay, gambling chips — okay, yeah, they’re chintzy plastic tokens — that disrupt that usual progress of play. One of them swaps the current trump suit. Another flips the trick upside-down so that low ranks beat out high ranks. And please note, these can be played mid-trick, ruining everybody’s day. Or you can swap a swap, restoring order at the last minute. Anything is possible on Cloud City.

The final tokens, bots and mobsters, alter the outcome of the trick. The former lets you claim a bonus even if you don’t win. The latter swipes an opposing card from the trick, maybe keeping you in the hand longer. In our most recent session, I’m convinced our winner pulled through entirely on the strength of their mobsters.

Does it work? Sure. It works great. At times it’s a little floaty — hardy har — thanks to its enormous deck, only a portion of which makes an appearance in any given round. This is necessary, given the game’s ballooning hand sizes, but it does prevent it from achieving kettle-drum tightness.

I’ll put it another way. Venusian Vegas isn’t a game I would turn down. But it also isn’t a trick-taker I’d go out of my way to play again. I appreciate its efforts to branch out; hybrid designs are where my thoughts are drawn these days, especially when there are a zillion of these things floating around. This game is at its strongest when it’s tinkering with convention. But for a game about a soaring casino, it still feels more grounded by those conventions than buoyed.

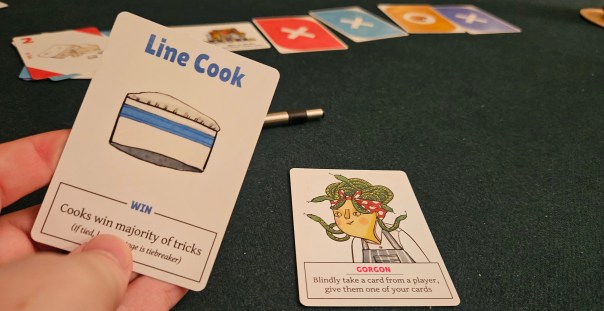

Beastro

It’s naturally tempting to say that Jason Corace and Matteo Uguzzo’s Beastro is The Bear, but really it’s closer to Burnt, the overwrought Bradley Cooper flick that apparently occupies the same cook-verse with The Bear, which is way more backstory than our Michelin Star-chasing chefs require. It’s the sabotage that does it. Beasto puts the innate competitiveness of these divas front and center. Because if you don’t get selected as this restaurant’s sous… there’s nothing for it but to burn the place to the ground.

The less wordy version is that Beastro interjects hidden roles into its trick-taking, and does so in a way that isn’t too far off from Cédrick Chaboussit’s Shamans. Each round features a new restaurant, complete with a pair of goals for everyone to chase. But thanks to an opening bid, one player becomes a head chef. They then assign a helper, in secret, while everybody else is relegated to lowly status as line cooks. The lines thus drawn on the griddle, these two teams duke it out to secure the most tricks.

As in Shamans, the ace up Beastro’s sleeve is that players don’t win as a team. To clarify, they win together within the span of a single hand, but since the teams are redrawn with each new restaurant, everybody’s score is kept separate. This gives shape to the game’s broader arc. If our first restaurant succumbed to disgraceful line chef coup, earning a heap of points for three of the players at the table, and then one of them becomes the next restaurant’s head chef, they’re likely to pick one of their disgraced former employers as their secret helper. That way, their shared win will still place the head chef’s score a comfortable distance ahead.

There’s gamesmanship to consider, is what I’m saying. Snippy, snitty gamesmanship, of the sort that transforms the kitchen into a lobster bucket.

A few small details keep the turn-by-turn trick-taking lively as well. There are two types of special cards, secret sauce and sabotage, which can be played off-suit, whether to secure a trick or release a few rats into the dining area right when the Michelin Man is hitting the third course. There are your chefs, each endowed with a single-use power that may well make or break an entire hand.

The biggest highlight, though, is the restaurants. Beastro may be a (temporary, changeable) team game, but those individual goals provide enough wiggle room for even cooperating players to break from the pack every so often. Valhalla Haus provides a bonus for winning exactly two tricks and winning the last trick. Pasta Palace is so about volume that it doesn’t mind a pile of sabotage. Pan’s Cakes wants to see a victory pile full of grain and no meat.

If anything, I wish Beastro had focused even more fully on the restaurants and the hairline fractures they can drive between teammates. There are occasional moments when a chef can feel some pressure to break with their team for the sake of an individual goal. This is when the game shines most brightly, bringing the blimp-sized egos of its protagonists to the fore. But these moments are temporary and distantly spaced, not the groundswells they could have been. For the most part, Beastro feels like a trick-taker with a side gig in hidden roles, not a full merger of the two. The result, then, is an uncommonly tasty tricker, but still one with a few chunks of imitation crab in its rangoon.

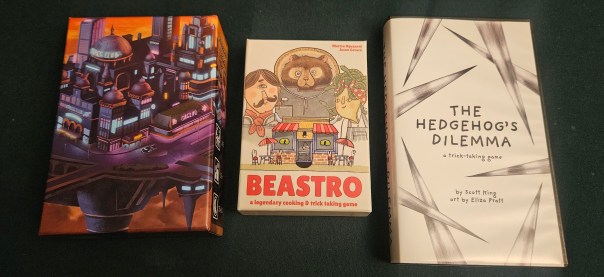

The Hedgehog’s Dilemma

Way back in 1851, emotional constipate Arthur Shopenhauer penned a parable called the Hedgehog’s Dilemma. As the parable goes, a prickle of hedgehogs take shelter for winter. Hoping to remain warm through the long cold months, they huddle together; then, irritated by their companions’ spines, they scoot apart. Back and forth they go, eventually reaching a point of minimum discomfort whereby they can share warmth without jabbing each other to madness.

Designed by Scott King, The Hedgehog’s Dilemma examines the social principles behind this parable in detail. This isn’t the first philosophical trick-taker of the year — that would be This Is Not a Game About a Pipe — but it’s a shockingly lucid illustration of its intended point. Honestly, if I were a philosophy teacher, this would become an instant project for fooling bored undergrads into making a sliver of effort.

But I’m getting ahead of the horse. Let’s put things back where they belong. The Hedgehog’s Dilemma is played on a map, a recursive infinity symbol of eight spaces, although two of those spaces, where the loop bends back over itself, are effectively the same apart from the relative facing of the markers sitting on them. Players are invited to use any markers that speak to them — this being an indie game, none are provided — so long as those markers convey facing. I opted to use the leftover ships from my prototype copy of Arcs. All the better for remembering how everybody in the universe got annoyed at me for writing a mixed preview of a Cole Wehrle game. Prickly hedgehogs, the lot of you! Now cuddle me for warmth. Mmph. Too close.

Ahem. The trick-taking is largely straightforward. The winner of the trick travels forward. One space normally, but two spaces if an eight was played. So it’s a race, right?

Wrong. Because no matter how far we go, we always loop back around to where we started. Very quickly, it becomes apparent that there’s no “winning” in the usual sense. Because this isn’t your customary trick-taker. I mean, come on, it’s based on a parable by a German philosopher. Winning is probably a construct or something.

When one player lands on another, something remarkable happens. A “poke.” Both poker and pokee mark their scoring sheets, indicating that they have now become increasingly familiar with one another. This ticks their values upward, from 1 point to 2, then from 2 to 4, then 8, 16, 32… all the way up to an unthinkable 1,024 points. That’s familiarity beyond marriage. Remarriage, maybe.

Hold on, what do these points mean? This is where The Hedgehog’s Dilemma starts to flex its smarts. When the hand ends, players assess their relative position on the track. If everybody is in the same space, congratulations: you’ve achieved equilibrium. Everybody wins! Well done, little hedgehogs. But if everybody is spread apart, not even two players sharing a space, then everybody loses. The winter has claimed human society.

But if two players are sharing a space, that’s when scoring happens. Everyone in the same space as another hedgehog loses points equal to their familiarity with their colocated player. Conversely, being too far away from a player means you score nothing at all. It’s only by sitting adjacent to a fellow warm body that you score points — and then only as many as your familiarity.

This means… a lot of things, both for the gameplay and for the game as a parable about society. Warming yourself between two clusters of rival hedgehogs is worth a lot of points. On the other hand, squatting atop an over-familiar friend sees your resentment simmering into a profoundly negative score.

All the while, players are free to cooperate or compete as they see fit. There’s an intriguing emotional core to the whole affair. Early in the hand, it isn’t uncommon to see players working together, counting out spaces on the track and swapping cards and manipulating the relative strengths of the deck’s four suits. But the instant it becomes apparent that total success is out of reach, everybody strikes out for themselves, often to their own peril. The result is a surprisingly crisp expression of a number of social concepts. The remoteness of ideal society and how we all too readily let the perfect become the enemy of the good. How communities suffer when our survival instincts crank our individualism into overdrive. Heck, how those same survival instincts can be dead wrong about which course of action will best outfit us for success.

It’s a brilliant little game, in other words, expertly designed and only accentuated by Eliza Pratt’s stabby illustrations. My main complaint would be that it doesn’t come with enough scoring sheets to play a hundred times. I’m already printing off more.

There you have it. All three of these trick-takers are unusually clever, and even go to lengths to ask heftier questions about our social condition than the genre usually permits. The runaway leader, though, would be The Hedgehog’s Dilemma. I’m going to find some way to use this in a classroom. I swear it.

Complimentary copies of Venusian Vegas, Beastro, and The Hedgehog’s Dilemma were provided by their respective designers.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, you can read my third-quarter update on all things Biff!)

Posted on December 16, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Beastro, Board Games, Geekery LLC, Hello Mountain, Indie Games Night Market, The Hedgehog's Dilemma, Venusian Vegas. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

Love these reviews!! Thank you for sharing your thoughts!

Thank you for reading!

I decided to leave a comment here instead of on the BGG because I want to be close to Space-Biff, but not too close.

My dilemna is whether I should pick up a copy even though I can’t think of who I’d play it with. I want to own just the right amount of games. Not too many and not too few.

Yeah, that’s a toughie. But surely you can find people to play cool trick-takers with! Trick-taking is one of the most accessible genres out there!

Tell that to my kids! 🙂

Pingback: Best Week 2025! The D.T.R.! | SPACE-BIFF!