Sun Besties!

At the risk of sounding like a backwater bumpkin, I’ll admit I don’t know much about Inca mythology. After playing Ayar: Children of the Sun, the latest collaboration between Fabio Lopiano and Mandela Fernández-Grandon after last year’s overstuffed Sankoré… well, I still couldn’t tell you much. As near as I can tell, we’re following in the footsteps of a creator god’s grandchildren, founding civilization in our wake. Planting corn, thatching islands, that sort of thing.

For a nu-euro, that’s par for the course, I suppose.

Despite the flippancy of its setting, Ayar almost immediately distinguishes itself from its predecessor by being comprehensible. Like Sankoré — and also like Lopiano’s Merv: The Heart of the Silk Road before it — Ayar is preoccupied with compounding action grids. Where early player activities are furtive and limited, it isn’t long before they’re empowered to twice, thrice, quadrice their original potency.

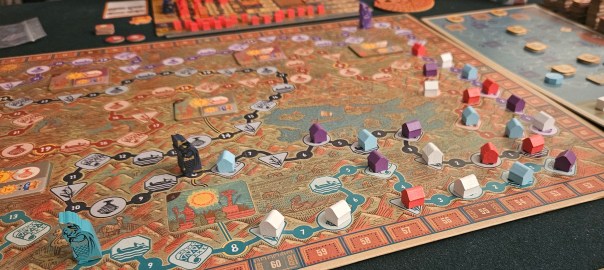

As in those titles, too, the central action-selection game spools outward to four mini-games — although, once more, here they’re simpler and less ornamented than their rather tinsel-strewn appearance in Sankoré. Planting corn is a straightforward majority contest between players. Thatching floating islands is a movement race. Weaving and pottery are markets, with a dash of icon- and color-matching. Simple. Right?

Not totally simple, but therein lies the game. If anything, Ayar is simple mechanically but complex in import. Depending on how you look at them, turns consist of either one big decision or a dozen micro-decisions that resemble one big decision. You shift a worker on your personal action grid, move the corresponding ayar across the land, select an activity along that ayar’s path, and conduct it. Along the way, any number of minor bonuses might trigger: domesticated llamas, temples placed on a track, little bursts of scoring. It’s a lot, but it’s all the “same” action, so to speak, but with long-term ramifications that tangle outward like a spool rolling down a spiral staircase.

My biggest takeaway is that Lopiano really, really likes action-selection and scoring grids. Calimala is one gigantic scoreboard. Merv transforms its grid into the walls of your Mongol-imperiled city. Even Shackleton Base doesn’t wholly escape them. Ayar feels like a distillation of these games into a system that’s at once indulgent and mercifully pruned to a more manageable state. There are enough considerations at play that each movement matters, but not so many that I repeatedly find myself lost among the clutter.

This allows Lopiano and Fernández-Grandon to tinker in other realms. For example, scoring. Points in Ayar are no simple thing. Rather than counting along the track with a single token, here players are asked to chase two separate types of victory points, with only the lowest becoming their final tally. Each is earned according to their own logic. Moon points are awarded every night based on completed activities: how many columns of blankets you’ve finished, the farthest you’ve traveled along the lake, and so forth. Sun points, meanwhile, must be triggered manually and are tallied via a dial, which then awards a compounding score every morning. They’re similar in the sense that every activity on the board potentially awards both types, but dissimilar in the type of effort they require. In mythological terms, perhaps we would say that the moon smiles down on completed labors while the sun rewards incremental steps. Slow and steady versus crossing the finish line.

Meanwhile, the board gradually narrows its scope. As those traveling ayar spread across the land, some fall behind and retire from the board — and therefore from players’ action grids. It’s a clever piece of design, decreasing the number of actions everybody takes in later rounds even as the efficacy of those actions grows more powerful. In the first round, you’re taking five wimpy actions. By the fourth and final round you only get two, but both of them are liable to swing for the fences. It’s a tidy way to keep later rounds from bloating, and rewards good planning to boot.

In this case, “good planning” largely consists of maximizing two spheres of influence. Lots of blankets with a side-hustle in island-thatching, for instance, or transforming yourself into the corn king of Tawantinsuyu with a head for pottery. This might sound overly straightforward, but it’s also one of the game’s few avenues for player disruption. Given the way the ayar drop out of their race across the board, along with the initial seeding of scoring tiles, there’s some room to sabotage a player by ensuring that the ayar who would trigger a favored scoring category never reaches their destination. It’s minor, is what I’m saying, but still present, even if it isn’t always apparent how exactly to disrupt a leading player’s plans.

When you get right down to it, that opacity is probably where Ayar struggles the hardest. While the turn-by-turn gameplay is undoubtedly simpler than some of Lopiano’s other offerings, it still feels like swimming up a waterfall of icons, scoring triggers, and hidden pressure points. There’s a curve here, but it’s something akin to the Chick Parabola. Learning Ayar is frustrating. Playing it halfway decently is intriguing. But then playing it well is dull. Up, up, and back down again.

That puts Ayar in a tight spot. It’s better than Sankoré by nearly every measure, but still struggles to reach the same highs as Lopiano’s best efforts. It lacks the openness of Shackleton Base, the distilled player agency of Calimala, or the integrated action grid and existential pressures of Merv. Instead it occupies the awkward middle ground. Worthy of a play or two, but not essential to the overall oeuvre of a modern journeyman designer.

Still, there are a few sights worth seeing along the way. The ayar meeples’ form-fitting bodies. Ian O’Toole’s lovely board design. The smart iconography around actions. The cool scoring system, with its dueling considerations. Another action grid. Always an action grid. I wish it had been a little more open-ended, and some actual detail about Inca mythology wouldn’t have gone amiss. But in the getting-to-know-you phase, Ayar makes for a good hang. Just don’t go expecting a lifelong friendship.

A complimentary copy of Ayar: Children of the Sun was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, you can read my third-quarter update on all things Biff!)

Posted on December 2, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Ayar: Children of the Sun, Board Games, Osprey Games. Bookmark the permalink. 1 Comment.

I recently had a go at Lopiano’s game Ragusa, which put me in mind of Hansa Teutonica.

I think it’s fairly objectively slightly more complicated than HT, but more striking is the similarity in how the rules sets are sufficiently abstract and unintuitive to make them initially seem subjectively more complicated than for instance Puerto Rico; even the much more complicated Agricola might be more approachable for a first-time player.