SDHist 2025: Day of Copium

This past weekend, I attended SDHistCon in San Diego, the most interesting board gaming convention currently running. Here are the official snapshots: the Summit Award went to War Story: Occupied France, the Bobby Nunes Memorial Award went to Amabel Holland’s video on the preservation of Kurt Vonnegut’s GHQ — thankfully beating out some doofus piece by yours truly — and I spent Saturday dealing drugs to unsuspecting victims.

In board games, mother. In board games.

Painkillers

My first session of the weekend set the tone for the entire event. Brooks Barber, whose Sykes-Picot earned solid marks earlier this year, asked if I would please wake up early for a session of Painkillers, his in-prototype title about the development of the opioid crisis in America. I’m only a morning person when I’ve looped around from the night before, but board games about predatory corporations are very much my jam, so I dragged these old bones out of the coffin for a sit-down with one of the most uncompromising titles I’ve played all year.

I’m glad I did. We were cast as the pharmaceutical companies responsible for one of the worst health crises of my lifetime. Our product was opioids. Morphine at first, but soon oxycodone, fentanyl, and, the instant addiction recovery became profitable enough, naloxone. Our target region was northern Appalachia, historically selected by the companies for its working-class population’s chronic injuries and the relatively low education of its doctors.

In its early stages, Painkillers feels much like any other points-optimizing eurogame. Companies invest to add their reps to various states, later transforming them into script-writing doctors and pill mills. Soon new users are added to the board. Eventually they may become addicts. By the end of the second round, more money was pouring in than we could spend.

Money, that old god Mammon, is the objective. But there’s a careful delineation between your company’s money, necessary for developing new drugs and staffing your company’s various departments, and the cash awarded to your family. That, of course, is perhaps the bitterest of the game’s bottle of rancid lozenges. While our corporations risked penalties or dissolution for their many many crimes, our personal wealth was safely tucked away in the bank.

Before that inevitable crash, however, there’s the long con to pull on the American public. As our reach across those struggling states grew wider, so too did our risk, requiring us to pull increasing numbers of tokens from a bag. Sometimes the effects of these tokens were positive. New users! How can that be a bad thing?

But new users means more eyeballs. Illegal markets soon appeared, sapping our bottom line. Activists began campaigns of their own, turning addicts into exhibits for public outrage. Worse, our activities also produced evidence that drew the attention of federal inspectors. At a moment’s notice, they might swoop in to shutter our pill mills or investigate our paper trails. In these cases, a robust legal department and the blame-game media became our best defenses.

In theory, Painkillers eventually reaches an inflection point. Too many deaths, too many addicts, and the whole thing comes tumbling down. Somebody might take the blame, but our personal fortunes remain untouchable.

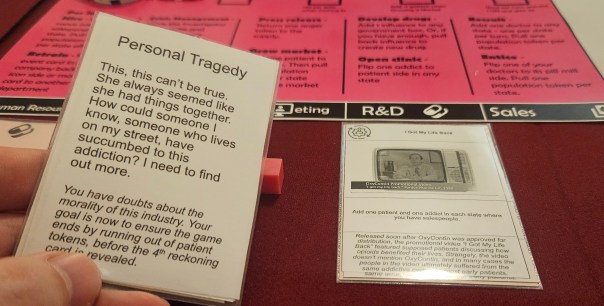

That isn’t how it went in our session. Instead, my CEO experienced a personal tragedy that caused him to turn on the industry. There are a range of possible twists in this vein. Barber showed us one where a player would be permitted to quit the game outright after one of their family members fell victim to their company’s drugs. In my case, my dunderheaded CEO felt the best way to investigate the morality of the opioid industry was to hook as many people as possible. When your only tool is a pill, everyone looks like a possible user.

Of the many games I played on Saturday, Painkillers was the roughest. The individual components are there, but the strands between them have yet to be fully drawn. Still, this one has real potential to highlight the abuses of an industry that targeted the vulnerable and largely got away with it.

An Infamous Traffic (Second Edition)

On the topic of targeting the vulnerable and largely getting away with it, I had no sooner finished my session of Painkillers than Cole Wehrle beckoned me over for a session of An Infamous Traffic. Specifically the long-in-waiting second edition. With my head still reeling from Barber’s contemporary accounting of the opioid crisis, I found myself staring down at the polyp that would cross centuries to metastasize into an addicted Appalachia. Was I doomed to experience this entire history in reverse? Spoiler: Yes. Much to my emotional peril.

For those who don’t know, the original incarnation of An Infamous Traffic was bookended by the first editions of Pax Pamir and John Company. This was the middle volume of Wehrle’s trilogy on the British Empire’s far-flung adventurism, and like many middle volumes it was the one that garnered the least acclaim.

Which isn’t necessarily surprising. It’s a rather weird game, for one thing. The historical games scene looked rather different in 2016 than it does now, nearly a decade and many niche imprints later. An Infamous Traffic was an early Hollandspiele production, paper map and weird-smelling counters and all. It didn’t help that Wehrle had yet to learn how to write a rulebook that made a lick of sense.

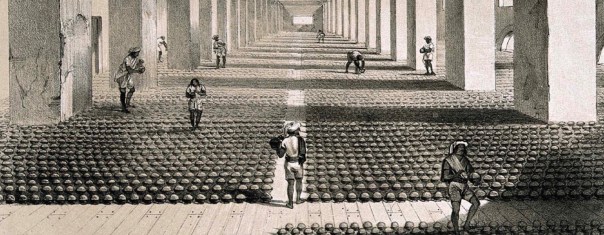

Yet for all its fumbles, An Infamous Traffic remained lodged in the collective consciousness. Or at least my consciousness. Where John Company recounts the history of the East India Company and the perils of enforced monopoly, An Infamous Traffic sets its sights on unregulated markets. I even wrote a big stonking essay on the distinction. Here, players command individual firms as they harvest poppies from India, smuggle opium into China, and then, when the hand of the great god Mammon is swatted away by the Qing Dynasty, petition Parliament to conduct some gunboat diplomacy.

Like Painkillers, it’s an uncompromising game, stripped of the pretty lies we like to tell ourselves about how these events went down. At the game’s outset, opium is banned in China. But recall, it was banned in England as well. Free markets for thee, carefully regulated vices for me. Meanwhile, our trade is plied largely in the shadows. Missionaries and smugglers, bribed bureaucrats, sloops off the shore in the dead of night, and eventually ceded ports, à la Hong Kong, are the tools of our trade.

As with the second editions of both Pax Pamir and John Company, Wehrle has expanded the scope of An Infamous Traffic without losing sight of its core experience. Your goal, as before, is to complete supply chains into China. But because these chains are sprawling, multi-step affairs, it’s customary for multiple firms to collaborate. And in most cases, mercilessly undercut their competition along the way.

But where An Infamous Traffic was often messy, this new edition has clarified a number of points. It’s a more wide-ranging game, for one thing. Rather than keeping its focus solely on China, your merchant family also spends time in London and India. There’s a minor engine-building component. My firm more or less cornered the opium market, producing the stuff efficiently and communicating with our merchants in China via our very own express post. Oh, and our poppy milk happened to be of the finest quality (read: most addictive), preventing our competition from undercutting our sales. There was hardly a supply chain on the board that didn’t stink of our product.

Physically visiting London has its own advantages as well. The original edition of An Infamous Traffic was infamous (hardy har) for its fancy hats, cementing Wehrle’s reputation as someone whose games hinged on a die roll, a trick we would see repeated in both John Company’s retirements and Oath’s denouements. The game showed how these merchants ruined thousands of lives so they could return to London and obtain a beneficial marriage, a nice cottage in the country, or a peerage. Or, right, a fancy hat.

Here, those fancy hats and other accoutrements are more present than before. The effect is fortifying on the game’s underlying message, not to mention crisper to play. Just as Pax Pamir shifted from being a game about clashing empires into one about the locals affected by those empires, and John Company shifted from pure adventurism to one that examined how those adventurers came home to pollute the politics that had enabled them, the second edition of An Infamous Traffic is more interconnected. Where your firms previously existed in a wonky non-space, now they linger in the wider network between London, India, and China. They’re clearly invaders in a place that neither wants nor needs them.

Look, it’s obvious I’m excited for this thing because I’m already essaying at you. But I can’t help myself. An Infamous Traffic still has some development in store, but it’s so much tighter than before. We’re one step closer to realizing my horrid dream of playing An Infamous Traffic within a session of John Company.

Speaking of which…

John Company: The Archivist’s Dream

Back in time I went once more, borne on ceaseless currents. The polyp had now rewound into a cluster of mistended cells, one bad mutation away from rebelling against its host. Also, by the time I was drawn into the bar of the S.E.S. Portuguese Hall for a three-hour marathon, I’m pretty sure I was well and truly cranky. At the very least, my stomach was starting to turn from all the opium.

Much has been written about The Archivist’s Dream, the megagame version of John Company. No longer do players command well-to-do families ransacking India for the benefit of their pocketbook. Instead, players become individuals within those families. My family, the Hastings, had a sturdy bank account but little influence: a military posting in Bombay, president of an underdeveloped Madras, a couple shares in the newly formed East India Company. With some mettle and a lot of luck, we might transform ourselves into a generational superpower.

Ha. Haha. Hahaha. That… did not happen. My own character, Walter Hastings, soon proved as incompetent as a three-legged powder monkey. When the game began in 1710, I had been given an enviable posting as the commander of the Army of Bombay. Wonderful! Perhaps I could cajole the president into setting aside some money for a military expedition. I would return to London covered in plunder and glory!

But time gets away from us. Drew Wehrle stood at the front of the room, passing the years in ten-minute increments. By 1712, a rival family had leveraged their superior position in Bombay to have me bumped down to a lowly officership. Very well, I figured, I could still profit from the invasion we just launched… except, wait, now it was 1713, and on the eve of our campaign — a campaign that netted shocking volumes of plunder, by the by — I had been transferred out of Bombay and into Madras. The only glory I would be covered in was a nasty rash.

This highlights both the advantages and disadvantages of The Archivist’s Dream, not to mention the broader megagame format. It’s rare for board games, with their emphasis on clarity of systems, to capture even a fraction of the communication problems that dogged empires and merchants for the vast bulk of human history. Before the Suez Canal, a swift voyage from London to India required three months. Weather and other inclements might double that duration. Sitting in that bar, with its dim lighting and clamoring volume, I waited expectantly for my plunder, only for the moderator to blow past. I wasn’t broke, but the entire family was poorer than we had been only a few short years earlier.

Which is also a bit of a problem. In theory, my character was over there in Bombay and later in Madras, and surely would have noticed their temporal dislocation from the battles he presumed himself to be fighting. At the very same moment, I was involved in negotiations with the Sykes family (hiss), hated by all, to furnish one of our ships. When they demanded too extortionate a fee, I was invited to write a letter about my frustrations, which I did, all those problematic British spellings and dangling E’s included, because The Archivist’s Dream is not only a game about families and empires and opium, but also about the way documents are produced. The clear highlight of the entire evening came when Drew read the best letters aloud to the room, a miniature history of our successes and failings.

Later, after our family had parlayed everyone’s hatred of the Sykes into having our man installed as the Company Chairman, the underlying purposes of The Archivist’s Dream came into collision. Imagine two tectonic plates shifting inexorably into the same space. The first plate is John Company, with its family-sized squabbles and victory conditions and all the rest. The second is The Archivist’s Dream, about individual fortunes and setbacks and misspent potential. At any given moment, I was superimposed across two separate lattices. I was Walter Hastings, his personal fortunes in tatters as he was transferred again to Bengal, only to be ruined anew when our fortunes there failed. And I was also the Hastings-Writ-Large, peering over our Chairman’s shoulder, checking our family’s accounts, and negotiating for a stake in the early opium trade. The game concluded moments before our grand ploy would have come to fruition. Or not. I can’t tell the future, even when that future lies in the distant past.

At any rate, these two tectonic plates were often at odds. Their collision may produce mountains. Or tremors. Or a volcano. I’m still uncertain which. The Archivist’s Dream was an experience unlike any other. I would gladly repeat it. But it was also uneven. It demonstrated a friction between families, individuals, and, yes, empires and their victims. But that friction remains unresolved. It was neither eased, making for a clear game state, nor did it catch fire. Mostly it just sat there. Bristling. Like a bramble in one’s waistband.

Still, The Archivist’s Dream was a purposeful capstone to a big day about drugs, empires, money, and bad behavior. As I walked back to the hotel that night, feeling the cool air on my skin, I figured no other game that weekend would prove so disconcerting.

I was wrong. But that will have to wait for another time.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, you can read my third-quarter update on all things Biff!)

Posted on November 13, 2025, in Board Game, Convention and tagged An Infamous Traffic, Board Games, John Company, Painkillers, SDHistCon. Bookmark the permalink. 3 Comments.

What a cliffhanger!

I’m a stinker!

Pingback: Unnameable | SPACE-BIFF!