Neither Board Nor Counters

I remember the first time I felt doubt. It was the night my little sister was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes. Mom figured it out at the grocery store — we’d been through this once before — and was sharp with us, but she let me buy a treat and for a while on the ride home everything seemed okay.

Then she said it. “I think Em has diabetes.”

There’s that pang even now. That lurch. Em was three. At home, we already had the equipment from my other sister’s diagnosis. The glucose monitor. The ketone strips. Mom was crying. Em was crying. I couldn’t tell which was worse, my mother’s grief or my baby sister’s wails. I went upstairs to my room and shut the door and prayed so hard it felt like my stomach would roll into a ball and fall out. Please, I said. Please, Heavenly Father, give it to me instead.

Nothing. No miracle. I didn’t really expect one, even as a ten-year-old. But no comfort, either. I cried, then went into the bathroom and nearly vomited, then crawled into bed and cried some more. When I looked out from the cocoon I’d built around myself, there was the treat from the store. Sugar. Something my sister would have to avoid from now on. I threw it in the trash and fled back to my blankets and that’s where the memory stops.

The Great Commission, designed by Simon Amadeus Pillardo and Paul Snuggs, is sometimes about doubt. Not often, but sometimes, and not always in a way the game seems to understand. Set during the early years of the Christian Church — strictly speaking before there were Christians or churches as we conceptualize them today — it is preoccupied with the evangelizing mission that Jesus commanded after his resurrection. Or rather, a particular interpretation and portrayal of that mission.

Soli Ludi

But maybe you don’t want to hear about The Great Commission’s particular interpretation of the great commission. Maybe you want to hear about how the cards move, what function they serve, which position on the table they ought to occupy. The game’s mechanical objectives. How to win and how to lose. The basics alone.

Very well. I can oblige.

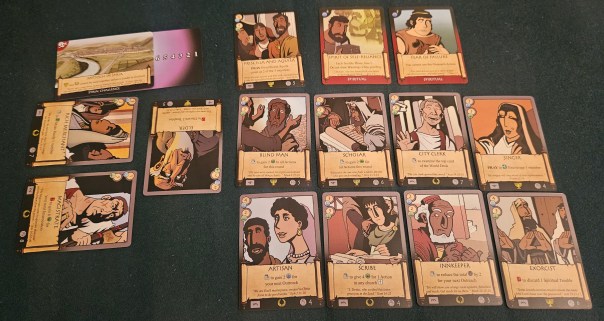

It begins with a church. If played with multiple players, then multiple churches. Leaders, too, and members of the congregation, drawn at random from a generous pool that becomes the foundation for a deck called “the world.” This jumble is one of the game’s greatest strengths, as aleatory and prophetic as thrown lots, dictating both your congregation’s potential and its weaknesses. A church in Caesarea will be a testy proposition for Jewish converts, while one in Ephesus will be haunted by extra trouble cards. Well-known figures like Paul and Mary Magdalene rub shoulders with those you might have to remind yourself about. For a dweeb like me, who spent his doctoral work focusing on the women of the period, it’s nice to see faces like Lydia and Priscilla represented.

And, of course, there’s your congregation. You begin with six members. For each player, twelve more have been shuffled into the world deck, eagerly awaiting your door-knockers to proclaim the word. This is the backbone of your labors. In game terms, your tableau. Every card is distinct. One session might see your fledgling group staffed by a linguist, a noble, a carpenter, a slave, a Herodian, a Sadducee. Not the most natural of friends. Indeed, there’s a distinction between Jewish and Gentile members, along with the potential for some mild rugburn between the two.

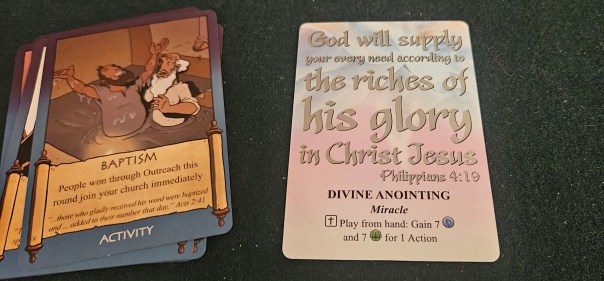

That congregation won’t stay the same for long, God willing. Because while there are distractions aplenty, your ultimate mission is to send your members out to convert the cards of the world deck. Mechanically, this is simple enough. By exhausting some of your members, you accrue a certain quantity of faith, then draw between one and five cards from the deck and check their resistance to conversion. If your faith matches or exceeds that number, swell! Those cards will be added to your congregation on the next turn. And if not, they’re shuffled back into the world. Maybe you’ll get them next time.

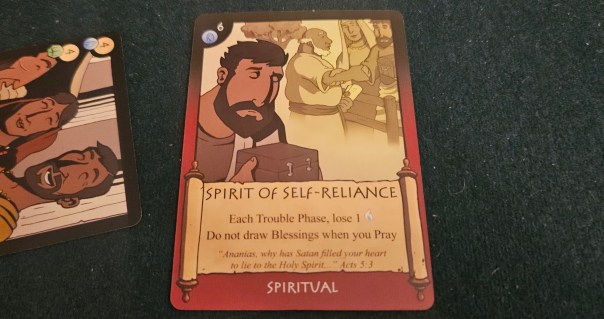

I mentioned distractions. There are plenty. Your church’s faith is always waning, necessitating constant prayer to keep your reservoir topped off. Meanwhile, a constant trickle of troubles appear from their own deck to afflict you. Troubles are initially played face-down and must first be revealed — “discerned,” in game terms — and then discarded (“intercessed”), a multi-step process under even the best circumstances. But this trickle threatens to become a flood as you recruit new members. In one of the game’s more human touches, converts may bring troubles with them. Sickness, pride, the occasional demonic possession. One of my friends has drawn the racism card in every single session. Solved it, too. We keep wondering where he’s been all this time.

The Great Commission functions solitaire, presenting your church as a lone warning beacon in the darkness. In multiplayer it tells a different story. Prayers can be offered for churches in far-off places. More materially, they can be sent aid in the form of members and activity cards. Blessings, the game’s ultimate power-ups, might attach spiritual gifts to your members or trigger powerful one-time effects. This hints at the early church’s communal nature more than stating it outright, but it’s a welcome inclusion all the same.

What else is there to say? The Great Commission is a functional game. It’s better than I expected, if not especially mind-expanding. The anxiety of its evangelizing, the pressure when too many troubles stack up too quickly, they are keenly felt at every point.

So, too, is the potential of your congregation. From a purely mechanical perspective, this is a game about hunting for and enacting synergies, and there are plenty of offerings to consider. My priestess discerns the troubles that afflict our congregation, then our soldier smooths over any internal disputes. Our city clerk informs us of what awaits atop the world deck, then our innkeeper uses his talent for hospitality to make our guests feel comfortable in the prayer circle. Our Nazirite prays to encourage a worn-out innovator, who then travels to one of our sister churches to lend assistance.

The overriding sensation is that of being simultaneously beleaguered and hopeful. When a member of your congregation dies, their loss stings. Provided you don’t just resurrect them, anyway. When somebody comes down with a demonic possession, it’s a real pain to cast the thing into some swine. When your entire congregation is tuckered out and you can hardly spare the actions to let them rest… well, yeah, that’s not the most exciting problem in the world. But it’s a relatable problem.

Do I like The Great Commission? Sure. Is it — pause for effect — fun? I suppose. Do I have hangups with it? Of course. But it’s significantly harder to talk about those than to detail how the game operates. But I need to try. I don’t think I would feel right with myself otherwise.

So. I’ll try.

Exe-History and Eise-History

Spend any time in Biblical history circles and there are some terms you’ll hear. Two of those terms, exegesis and eisegesis, are particularly loaded. Both derive from the Greek word hegeisthai, literally “to track” but more figuratively “to guide” or “to lead,” which is incidentally also the probable root of “hegemony.” Their prefixes, meanwhile, are opposites. Ex means “out of,” eise means “into.”

Summary: exegesis means “guide out of,” while eisegesis means “guide into.” When you practice exegesis, the idea is that you’re letting the text guide you. Practicing eisegesis, on the other hand, means you’re guiding the text.

Right away, though, we run into a problem. Because it turns out that reading ancient texts is hard. For one thing, very few people actually bother. It’s more common, for obvious reasons, to read translations of translations, mediated through translators and interpolators and tradents and critics and theologians and heretics and amanuenses, all in a long line of transmission, all of whom have left their own fingerprints and ink-smudges on the book that has come to sit on one’s bedside table.

Since we’re spending time in Biblical history circles, it also becomes swiftly clear that everybody thinks they’re doing exegesis while everybody else is doing eisegesis. The text is not one thing. It’s a sprawling, complex, often contradictory Rorschach test. And like a Rorschach test, the image it presents is completely obvious to whomever is describing it in the moment — and often only to them.

Take, for example, the Rapture, the end-times event when dead Christians will be resurrected and those still alive will be taken up to meet Jesus. Living in the United States, one might assume that the Rapture is this universally agreed-upon event. It’s the entire basis of those freaky Left Behind books, for heaven’s sake! But the Rapture is a fairly recent innovation, dating only as far back as the 1830s, and most Christian denominations don’t agree with it. For many Christians, the perspective of Evangelical Protestants qualifies as light heresy, potentially harmless but nevertheless wrongheaded. Show two Christians the exact same passage in 1 Thessalonians, even from the same translation, and you might hear two totally different perspectives on its meaning. Now ask them whether they’re performing exegesis or eisegesis. Of course, nobody’s going to cop to the latter. Both are only reading the words in context. It’s their opposite member who’s inserting their cultural assumptions into scripture.

To be clear, these theoretical exegetes are not emblematic of all Christians. Many are humble and curious and willing to hear out their fellow interpreter. Nor is this to argue that Biblical history is hopelessly subjective. Only that it’s very hard, and very slow, and very much about the practice of doubting one’s sources, convictions, and received traditions. Above all, it’s challenging. Because if we look into the past and see only ourselves, we aren’t really looking into the past. We’re looking into the mirror and seeing ourselves in cosplay.

When it comes to an artifact like The Great Commission, I mentioned earlier that it presents a particular interpretation of Early Christianity. As with all interpretations, some details don’t matter. If I were to look at the illustrations and gripe that the Roman commander’s cingulum isn’t drawn exactly as they were manufactured, that wouldn’t be a substantive critique. It’s clear that this game was crafted with care and attention, that it hopes to convey something true about how these events played out.

But that portrayal is looking through the glass darkly. Or, perhaps more accurately, through the mirror of what (some) modern Christian churches look like. They’re churches, for one thing, urban and cosmopolitan in nature, with congregations of integrated converts from a wide range of backgrounds. To some degree, this is an accurate portrayal. The early movement that became Christianity was, in some places, a rather diverse cast, cutting across boundaries of class, culture, and gender.

In other senses, it doesn’t quite hit the mark. There’s none of the domesticity of those early house-churches, none of the sense that these were some of the few spaces in the Roman world principally led by women. Nor are they especially Jewish, despite the presence of Herodians and Pharisees. The issues they face are more modern than ancient, the persecutions they endure are more organized than they were in this period, and there are references to heresies that will not exist for centuries to come.

Now, these are critiques I hesitate to offer. We’re talking about a board game, after all, and a slender one at that. Of course there are omissions. Not everything can be included. But these churches, with their member-by-member emphasis on an evangelizing mission, their close-knit collaboration between far-flung congregations, and their siloed internal problems, present a rather cozy vision of early Christianity indeed. There are disputations, of course, but they’re troubles to be resolved at your church’s earliest convenience. There’s no such thing as, say, my church and your church having a falling out over some fledgling issue of doctrine.

The irony is that ancient Christianity looked very much like modern Christianity — complicated. Even in its earliest stages, this was a tangle of competing ideas and beliefs. Despite thinking it’s sticking to “just the facts,” the authors of The Great Commission put down stakes. It’s more Pauline than Petrine, more Evangelical than Catholic, more masculine than feminine, more Gentile than Jewish, more ideological than material, more futurist than apocalyptic.

Look, I’m not saying I don’t like the game. On the whole, I’ve enjoyed my time with The Great Commission. I would even use it to demonstrate certain things about the period. But those demonstrations would come with long list of qualifiers. This is a presentation of an ideal, scrubbed of the messiness that makes the period such a thrill to uncover but also so uncomfortable for those of us who came to the history because of our faith. It’s a presentation that some folks will look at and, thinking that they’re performing exegesis, say, “Yes, this is how it was,” without realizing that it’s eisegesis all the way down. Much like everything else.

Because, no, this isn’t how it was. It was many more things than this. It was larger, and wilder, and bloomed with many more flowers and fruits and, yes, poisonous mushrooms, too. But to talk about that, we would need a very different game indeed, one that is a little more questing and a little less willing to believe the stories it tells about itself.

A Secular Sermon

When I started writing about The Great Commission, I said it was a game about doubt. That’s true. Only the doubts are always somebody else’s. They’re the doubts of the Greeks and the Jews in the world deck. They’re the doubts that lead the eunuch to demand baptism right this very instant. They’re the doubts that make for great pulpit pounders, sending shivers up everybody’s legs. But it’s doubt all the same. Because to ask somebody to believe the gospel you’ve brought, there’s no escaping that you’re also asking them to question theirs.

Sometimes a student will ask to meet with me. Usually, I can tell what’s coming. I have office hours for the usual stuff, help with papers or a master’s thesis, but these conversations require their own block of time. I’m happy to listen. That’s what it comes down to. Listening. Because even though they’re the ones asking me a question, what they really need is somebody who will sit with them for an hour. Just to hear what they have to say.

“How can you still believe?”

I’m as disappointing a believer as I am a teacher. Because, at that moment, what they want to hear is the answer. The thing that will resolve the doubts. But I don’t have that. I haven’t resolved the doubts. Most days, I don’t believe in anything divine. When I pray, I don’t expect an answer. Sometimes I think the only thing I’m good at is doubting.

Here’s what I do believe: we can make this world a beautiful place. We can feed the hungry. We can clothe the naked. We can visit the prisoner. And we never needed a Rapture to do it. But the people who insist on the Rapture are always coming up with explanations for why we don’t need to do those things. Reasons for the death penalty, or why women shouldn’t be allowed to control their own bodies, or why I need to worship the same runty emperor as them, or why we shouldn’t fund school lunches for starving children, or why it’s okay to shoot priests in the head with pepper balls. Christian priests. My God. They tell me we’re being persecuted as Christians, but they always chase it down with a list of reasons why it’s not a big deal when the persecution comes from other Christians. Something about eisegesis, maybe.

More often than not, this is what those students tell me. It isn’t the complicated stuff in history that does it. Sure, that stuff is challenging. It doesn’t conform neatly to the words in the book. But what really tears them up — what tore me up — isn’t all that. It isn’t even my secret agenda to de-convert them from their childhood religion. (That’s a joke.) It’s the way the faithful, at least the loudest ones, can’t seem to handle the slightest strain. It’s the way they react with such venom to curiosity, to people who are on their side but not in the most traditional way, to those whose needs are out of step with their own. My students don’t ask, “How can I make the world fit together again?” They ask, “How can I fit into this church that won’t make room for me?” Whenever I write about religious board games, I receive death threats, among other things. “You’ll burn in hell.” Okay. “You let yourself lose your faith.” Correct. “You’re lucky we don’t do crusades anymore.” Aren’t we all. These notes never come from atheists. Never once from a Muslim. Always, every time, from followers of Jesus Christ.

When I play The Great Commission, there is a bright moment when the game is simultaneously at its best and at its worst. It’s when I look down at my congregation, all those members from a half-dozen backgrounds. Many faces, many hands, pulling toward the same goal. There’s a verse in Galatians that many scholars believe is an early baptismal formulation. “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

I find that beautiful. Even now.

But you know what I find even more beautiful? The idea that we can coexist without the prerequisite of conversion. That we can be neither Christian nor nonbeliever, neither doctor nor working class, neither cis nor trans, and still treat one another with dignity and respect and an eye toward our mutual prosperity.

The Great Commission brushes fingers with the possibility. But it pulls back. In presenting these churches as mundane, common things, as fitting into that singular model — when it looks into the mirror and thinks the image staring back is as good as it gets — it stops short of revelation.

Amen.

Welp. That was pretty heavy for a board game review. But there it is. The Great Commission. It can be purchased from Word for Word Bible Comics for £34.99. Just be careful about the coins you exchange for it. I’ve heard some might have Caesar’s visage stamped on them.

A complimentary copy of The Great Commission was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, you can read my third-quarter update on all things Biff!)

Posted on October 29, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Alone Time, Board Games, The Great Commission, Word for Word Bible Comics. Bookmark the permalink. 28 Comments.

Dang, that’s expensive. Do you suppose they’d accept a widow’s mite?

Not sure, but I believe they don’t accept any funds that have been buried in the ground.

Thank you so much for this, Dan.

Thanks for reading, Bob.

Maybe with a teacher like you I would have reconciled some kind of faith with the beautiful world that I also believe is possible to create.

Thanks for teke the time (and I guess courage, specially on the current times) to talk about this topics and perspectives. A board game, as any cultural object not only exist, it also shapes the world around it even if it’s just a little.

Is this kind of essays that open my mind to the expressions on this objects, the good and the bad ones. To be able, at least for a moment to recognise our own glasses and see the smudges that change the image, the colors that try to make it something else. To remember that those glasses are always there, in front of our eyes.

Thanks, Hugo.

I relate to this deeply on so many levels. What a funny thing to find in a board game review. Thanks for writing this, Dan.

Thanks for reading, Nate.

Thanks a lot, Dan, for writing the review. There’s a lot to unpack here, more on tangential thematic issues than so than just the game.

The game is intended to be as accurate as “possible”, but with so many moving parts and potential combinations (i.e., trillions), the game cards do not always fall in the perfect combination to give sound exegetical doctrine.

We hope the game will be fun, first of all, but open conversation about faith, belief and the Bible, not to solve and seal the matter.

I know that the biblical theme in general will be one that people will have a range of reactions to, but I’m a little surprised at the level of critique of the minor thematic elements of the game. I wouldn’t expect that a review of Dice Hospital will detail medical ethics or inconsistent clinical procedures. It seems to me that if this level of doctrinal discussion can be pulled out of the game and examined so closely, then it’s an indication that the game it does manage to include a rich, multifaceted presentation of the Early Church history and its struggles within the cards and mechanics, if not a perfect one.

For anyone interested, here’s more discussion on some of the points raised:

One of the critiques you raise is about women in leadership, but the game has several women who can lead your church. You can also appoint others when, mid-game, if you get activities or blessings that do so. The game is actually relatively flexible in regards to players’ personal cultural presuppositions because (for example) if someone had a conviction against women historically in leadership, they could use the cards in a restricted way. Whereas others who are open to it can use the cards in the standard way.

One of your big critiques is around the Rapture, but in the game, the Rapture doesn’t feature. I’m concerned that the broader context of the comics has colored your critique of the game when, in fact, the game doesn’t give exegesis or eisegesis about the Rapture in any way.

In the representation of the Early church (as cards), you state the church is “more Gentile than Jewish”. With Jews and Gentiles People Cards, we have a roughly even split, but the split of leaders is heavily weighted in favour of Jews. So I don’t think this critique is valid. (Note: The members had to be balanced as there are cards which affect one or the other, and we wanted the mechanic to have an even spread). Also, “more masculine than feminine” again, this is a roughly even split, but with more men in Leadership (it is the first century after all). “More Evangelical than Catholic,” neither denomination had truly begun in 30-90 AD, so that’s not relevant.

I’m really grateful for the effort you’ve put into the review, and I’m pleased to see that it sparked such considerations and discussion.

Creating a group of people w/ uniformity of thought seems like an intrinsic drive of mankind; that’s why some people instinctively respond with such venom to doubters.

We see this with the dubious rush towards true AI, which would not just be a workforce, but would create a population of uniform, controllable minds. The benefits of that go beyond just working; you could wish greater goals into reality as well. (As an example, we can see the ‘accomplishments’ of the Israeli’s, a people successful in uniformly extinguishing all doubt of their own humaneness, and thus can reach depths of hell the rest of us could not begin to approach.)

Hello Dan, thanks so much for trying the game and for your really interesting write-up.

I would be very interested in discussing (maybe offline to this review) why you thought there was a lot of eisegesis in the game.

We tried very hard to be as close to scripture as we could.

Many thanks,

Paul Snuggs

There’s so much I want to say, but that might detract from how seen I feel right now. So instead I’ll just say ‘amen.’

You keep knocking it out of the park, Dan. You and Amabel have a way of getting personal th

Wow, I didn’t think I was going to finish this epistle and I’m so glad I did. The game sounds fascinating…I, too, am very curious about early Christianity.

Paul Snuggs, above, wrote: “We tried very hard to be as close to scripture as we could.” Yes, but which scripture? The scripture that was chosen over dozens of others, right? And does scripture = history? Certainly not! So that’s a problem, aside from game mechanics.

I’m a big fan of your credo in the middle of your review. That’s basically where I am, too, but I’ve accrued so few VP! 😉

That story about learning about your sister’s diagnosis sounds so painful. There’s a Swahili word “pole” (pronounced “poh-lay”) that translates to “my condolences for what you are going through and/or went through” with connotations of sympathy, solidarity, and support. Pole.

My biggest doubts similarly have come from the hard things my sisters have gone through. Ironically, the way my sister’s faith grew in spite of her painful circumstances is what has gotten me through many of the doubts.

I’m not on board with the idea that “coexistence without conversion” is the most beautiful vision, but mainly because I truly believe everyone deserves the love, joy, and peace that Jesus has given me. If “conversion” means discovering Jesus and the full, eternal life He gives, I want that for everyone. But in your words I hear a heart that values loving relationships over firmhanded religiosity, and in that we can agree.

Thanks again for a great article about board games.

Michael, I think you get this from your post, but as soon as you even start down the road of, “I want that for everyone” and “I truly believe everyone deserves”, you are entering the terrain of you knowing best, coercion, and authoritarianism. Coexistence cannot be grudging just as love cannot be grudging.

I tasted a great donut at a nearby shop. I recommended it to a friend. Am I therefore entering the terrain of me knowing best, coercion, and authoritarianism? Or is it possible that you’re imputing a harshness to my thoughts and actions that isn’t there, for the understandable reason that I claim the same faith as others who truly are so harsh?

I hold no grudge against the atheist who lives next door to me – I have no desire for forced conversions, and I respect each person’s freedom of belief. Simultaneously, in a spirit of generosity I do not allow myself to be stingy with the hope I’ve found, for the obvious reason that we all love to share our most meaningful experiences, ideas, and relationships with those we love.

All the best to you.

Michael, I’m not imputing any harshness to your posts, as I said, because I read what you said in your first. However, let’s be clear: recommending a donut shop to a friend (who is hopefully not dieting or on a gluten-free or sugar-free regimen) is not at all the same as “If “conversion” means discovering Jesus and the full, eternal life He gives, I want that for everyone.”

You must know by now that being aggressive with your “spirit of generosity” will not bring the results you seek and will often backfire. There is still the whiff of “I know best, therefore others should heed me”…well, what if you don’t know best, or know best according to your chosen audience? You only know what’s best *for you* according to your identity, not what’s best or even attractive to anyone else.

Yes, there’s definitely a difference between recommending donuts and recommending a faith, no metaphor is perfect.

I don’t use social media and rarely comment on anything online, but the reason I’m continuing this conversation is that it’s somewhat baffling that you, a stranger, have decided I’m “entering the terrain of… authoritarianism”; that the way I coexist with those around me is “grudging”; and that the way I share my faith is “aggressive”. Have we met?

I simply have a different idea than Mr. Thurot of what the most beautiful vision is. As I understand what he wrote here, the highest beauty is found when believers and unbelievers of various stripes exist alongside each other in friendly affection. For me, the highest beauty is found in Jesus, and I don’t mind sharing as much when the opportunity arises, though neither will I shove it down anyone’s throat. Of course, the second highest beauty just might be Space Biff articles. I’m sure you and I can agree on that?

Happy weekend! I bet if we met in person we’d be friends 🙂

Michael, if Dan says “the highest beauty is all co-existing together” and you respond, “no, it should be my religion!”, that’s dominating and authoritarian. Not sure if you understand that. Your response does not read as generous, compassionate, or sympathetic AT ALL.

What would it look like in your mind for someone who follows Christianity to co-exist beautifully alongside you? Surely “my faith in Jesus is the most beautiful thing in the world to me” would be an acceptable thing for such a person to say? If such a statement is anathema, I can’t wrap my mind around what coexistence must mean to you. Are you picturing a world where all people hold to their private belief systems and do not admit that they like it, nor recommend it to others?

And what’s the authoritarian, dominating part of believing others might benefit if they had the same faith as I do? Isn’t this what many people of many faiths believe – after all, why follow a religion if you don’t think it’s the best one? I acknowledge that some faiths specifically include beliefs like “each person should find their own enlightenment”, but billions of humans follow major religions that make exclusive claims to the truest view of reality. To coexist with such people, one would have to allow them to believe and express such.

In my mind, “dominating and authoritarian” are words to describe someone who attempts to force their faith upon others by threat, violence, manipulation, shows of power, or other forms of state-sponsored and/or individual coercion. Simply typing some words online like “you picture one utopia, I picture another, thanks for the article” is something I would describe as friendly, neutral, or at worst, time-wastingly banal. It’s a bit frustrating feeling like you’d like an apology from me simply for stating a pretty basic expression of my faith.

If my words aren’t coming across as generous, compassionate, or sympathetic, that’s probably because we’re having a disagreement, and it’s hard to interpret tone over text. But please trust I have mostly positive feelings towards you, a fellow board game lover, mixed with confusion over how badly misunderstood I feel by you.

May your Monday not suck, and your next board gaming session be memorably fun!

That funny feeling when a couple theobros insist they can understand ancient documents while misunderstanding a board game review.

Dan, I think it’s pretty clear that if your environment included enough more Muslims, Hindus or Buddhists, then you would encounter a similar range of responses. The spread in the Abrahamic family of traditions, however, also clearly inclines more to some attitudes; I think this reflects a profound influence from the early context of desert nomad tribes.

The designer seems to have missed the real point of some of your observations, wandering off into pettifogging. That’s an inherent risk in bringing to bear the larger context that makes your critical work so much more interesting than the run of the mill of game reviews!

Anyhow, thank you for sharing your work. It’s always worth reading even if I’ve no especial interest in the game artifact itself.

Dan, I would like to pose this question directly to you. Above, the designers offered their responses to your review. Some of their statements seem off base, but others seem reasonable enough. Have you considered answering them line by line? I think we might benefit from hearing your perspective.

I don’t see the point.

I usually always have a strong feeling in one direction whether I’m going to get past the “bump/preview”, and click the post in full. This time I was so glad I didn’t gloss over the title and got hooked in by your initial words. This post speaks to so many of my own doubts and was a gem of an eye opener into your human experience. I shall be bookmarking and reading this one several times over. Thank you.

Thanks for the kind words, Jake. I’m glad you got past the intro!

Pingback: Die Verweigerer der Klimakrise haben einen wahren Kern in der Rettung der SPD vor den Sozialreformen - Vermischtes 04.11.2025 - Deliberation Daily