Horatio Hotwindblower

There was a time when news of another entry in the Pax Series was cause for celebration. Ah, to once again be a callow youth! Nowadays I identify as a callow adult. Pax Hispanica is the eighth installment — or is it the tenth? — and as a solo Phil Eklund outing, it has that “opinionated uncle at Thanksgiving” energy going for it.

But this time, Pax Hispanica sprinkles something extra atop its what-if history, double-take footnotes, and overstuffed glossary. In a first for the series, this one is also a big old bore.

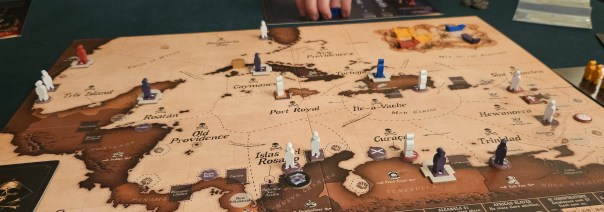

Welcome to the Spanish Main. When Pax Hispanica kicks off in the early 1600s, Spain has established her first colonies in the New World. Ships laden with pearls, salt, and silver are bound for Europe. Missionaries carry the word of Christ into the jungles and mountains. And enterprising captains, empowered with letters of marque, set out to earn their fortunes.

But for all its familiarity, this is an earlier Caribbean than the one of popular imagining. The first sugar plantations have yet to be established. Black markets are essential to Spain’s nascent colonies, but the golden age of piracy is still half a century out. Indigenous slavery is the norm, not imported slaves from Africa. Conquistadors are still hacking through the foliage in hopes of stumbling across El Dorado.

The Pax Series has always thrived in liminal historical spaces, those watershed moments when it seems like history could have (and in some cases, did) develop along any number of theoretical leylines. In that regard, the 17th century is no different from the Renaissance, the Great Game, or the transhuman revolution. The entire world stands at the cusp of something. What that something entails, specifically, has yet to be determined.

This is the first of Pax Hispanica’s touchstones to the series at large, and it won’t be the last. Foremost among those touchstones is your role in this flashpoint. Rather than assigning control of a nation, as in most games about colonialism, here you are an individual freshly arrived in the Caribbean to make your name. Along the way, your character will develop their perspective on the world, growing from a callow youth to an extremist of one stripe or another. In fine Eklundian fashion, “callow youth” and “extremist” are actual game terms. No surprise there. This is the same designer who included menopause as a game mechanism in Bios: Origins.

Okay, so what do all these fanciful verbs actually mean?

In game terms, your character begins in the middle of a compass of possible ideological positions. They are “callow” because they haven’t yet made up their mind about what sort of person they will become. From these middle positions, shifting onto one of the four compass directions establishes your profession and, eventually, the possibility of extremism. One character might develop a taste for royal expansion, only to succumb to a midlife crisis and instead pursue their own fortunes as a buccaneer and governor. Another might earn their initial nest egg as a colonist, happy to leverage slave labor to produce as much silver as possible, but then have a change of heart and spend their last days championing abolition. It’s an intriguing representation, capturing some of the dynamism and reversals of opinion that marked the lives of figures like Sir Walter Raleigh or Bartolomé de las Casas.

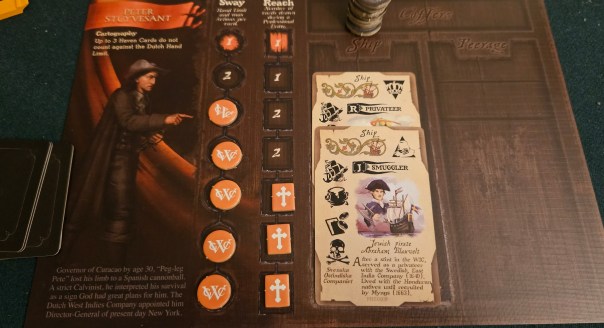

At the same time, this compass is also a huge pain in the ass. Leaving aside the game’s production, with its icon-obscuring standees that would have been better served by wooden discs, there are tangible benefits to developing your character first into a professional and then into an extremist. It’s the main route to victory, for one thing. This is no country for the lukewarm. But beyond that, moving your character from the callow spaces onto a profession track is one of the best ways to secure cards. Normally you’re subject to an auction, everybody putting up a single card for bid and then passing it off to whomever pays the most. But as a professional you’re eligible to skip this auction altogether, instead drawing cards from your chosen profession deck.

Note that this isn’t always useful. Cards do the usual Pax things, triggering actions and adding pieces to the board, so you always run the risk of drawing something that doesn’t quite gel with your plans. But they also nudge your position on the ideological compass. If played in the right sequence, it’s possible to crawl forward along your chosen profession until you become an extremist and therefore eligible to win. Along the way, though, it’s possible to step off to the side of your chosen track, effectively walking the plank of your own ambitions. This can result in a mutiny — becoming an abolitionist on a slave ship is a dangerous affair — or a midlife crisis. That latter outcome is considerably less dangerous, since you can assuage your doubts by buying a fancy carriage. But in either case, falling off your profession track boots you back down to the middle of the compass, callow all over again. It’s the Pax equivalent of moving back into your college dorm after getting laid off from your previous job.

In one regard, this is more or less what every Pax game asks you to do. In place of the series’ usual open market, cards are auctioned or drawn straight from the game’s four decks, but the outcome is the same. You take these disparate cards and try to cobble them together into a coherent plan of action. It’s another step removed from the core market manipulations of Pax Porfiriana/Pamir/Renaissance/Viking than even those of Pax Emancipation or Pax Transhumanity, but it works well enough.

Until you factor in those ideological implications, anyway. Every single card nudges your character on the compass. This makes many of them useless or, worse, counterproductive, consigning your character to an attack of conscience or beefswelling of greed that will steer them off your chosen path. Rather than checking the marketplace for specific icons that will forward your board position, it isn’t uncommon to select bids on ideological thrust alone. “This card will move me left, but I need to go right, which means it’s okay to shift upward because I can pay off my midlife crisis… okay, so I’ll buy one of the two cards that doesn’t hurt me.” The cards are simply less malleable than those found in other Paxes.

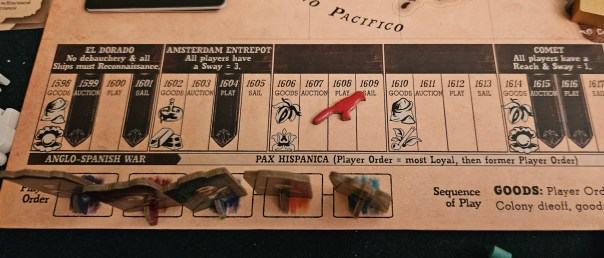

And this isn’t the only thing that’s less malleable. The structure of Pax Hispanica eschews the freeform trappings of its peers. The game proceeds according to blocks of four years. In the first year, goods are produced in colonies with sufficient labor, while others go the way of Roanoke and disappear. In the second and third years, cards are auctioned and then played, while the fourth year sees you pushing around little flotas to haul cargo, steal slaves, carry colonists, or conduct pirate raids.

The passage of years, meanwhile, is strictly jacketed. In the earliest block, ships are limited to reconnaissance actions thanks to all those adventuring conquistadors. Later, the number of icons you can use on a card might be artificially inflated or nerfed. 1618-1621 are hurricane years, causing any interdicted fleets to be immediately sunk. Malaria rears its head, but only in 1626 and 1642. The Thirty Years’ War begins in 1618 and lasts the remainder of the game. Unlike other Paxes, which treated their flashpoints as moments when the future couldn’t be known in advance, Pax Hispanica proceeds in an orderly fashion through set events.

All that said, there is one thing Pax Hispanica treats as malleable: its approach to history. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the game’s treatment of slavery.

It begins well enough. To generate cash, you need to ship goods back home. To produce those goods, a colony must have labor. To secure this labor, at least in the game’s early stages, pawns are kidnapped from nearby indigenous sites. Then, once the goods have been produced, the slave is removed from the game. You have quite literally worked them to death to produce salt, silver, pearls, tobacco, cocoa, or whatever else the folks back home have developed a taste for.

As board games go, this is an unflinching portrayal of the horrors of slavery. It is brutal, inhuman, and unsustainable. I could not appreciate its honesty more.

Except Pax Hispanica then tosses the whole box out the window. As native populations dwindle, it becomes necessary to secure labor from other sources. These can be imported from Africa (accurate), respawned at depopulated indigenous zones via the voodoo icon (um), or you can use your missions to teach the natives literacy, at which point they become citizens, seek gainful employment in nearby colonies, and generate wealth because they are engaging in non-compulsory labor in exchange for wages.

Which, in case it needs to be said, is not something that happened.

Not only did it not happen, it’s the exact opposite of what did happen. Caribbean colonies — managed largely through investment companies — used slaves of one stripe or another until they were forced to stop, whether through slave uprisings or agitation back in their home countries. Even then, the shortage was made up through indentured labor or gradual emancipation programs. In its current incarnation, Pax Hispanica reads like a libertarian fantasy where joint-stock and charter corporations saw the light and decided to pay fair wages for fair work, rather than murdering their laborers wholesale whenever they decided to stop working.

I’ve made the case elsewhere that Eklund’s historical board games will often say one thing in the footnotes while ludically arguing the opposite. As to the first qualification, Pax Hispanica is loaded with some real zingers, like the one about how a certain species of oyster went extinct because nobody had been introduced to Lockean property rights, as opposed to, you know, the locals being enslaved to strip-mine the coast for pearls. Unlike some other recipients of Eklund’s work, I don’t believe him to be an apologist for history’s many horrors. He clearly despises slavery — although he lumps such a range of unfreedoms under the header that its definition is eroded to the point of meaninglessness — and he celebrates literacy, education, and open borders. But for all that, he seems particularly credulous about colonialism’s many lampshades. Missionary work becomes a categorical good, uplifting and en-literacy-ing the natives despite all the god stuff. The swift conversion of the indigenous from animism to monotheism becomes, wouldn’t you know it, a symptom of the breakdown of their bicameral mind — which in case you haven’t brushed up on your pseudo-psychology, would mean the natives were not conscious actors in the same way that you and I are conscious. That would come as one heck of a surprise to Bartolomé de las Casas, since his defense of the indigenous to the Spanish Crown relied on their status as rational beings. Eklund points that out elsewhere, by the way. If you were to place this game on its own ideological compass, it would be somewhere on the moon.

Every so often somebody will ask the question outright: Is Eklund a racist? This isn’t the sort of question I like to consider, because, one, I’m not in the business of peering into the soul, and two, despite some truly awful opinions being ascribed to the man over the years, many of these aspersions never seem to be entered into evidence.

But talk to me enough about how such-and-such group benefited from their enslavement, how native Amerindians were experiencing auditory hallucinations from their gods until the missionaries unlocked their brains’ full potential, and how your pocket definition of the Enlightenment proves universal laws of not only science but also morality, and I’ll begin to look at you sidelong. Add in a gameplay model that sees your converted natives becoming eager wage-earners for otherwise rapacious financiers, and… well, at that point, I’d rather just call you a crank.

Now it’s time to insert an image of Britta Perry saying “I can excuse racism, but I draw the line at boring gameplay,” because if these problems weren’t enough, Pax Hispanica is also a chore to play. It’s a bloated, overlong, tedious mess, chock-full of specialized rules that add precious little to any given session but which necessitate their own glossary entry, reference card, and probably rules thread on BoardGameGeek.

I won’t take up your entire day with examples. Instead, I’ll offer only one: the sailing phase. This is simultaneously the game’s most amusing and most confounding portion, asking players to buzz their flota from one sector of the Spanish Main to the next like a kid going brrrr with a toy motorboat. You move your ships into the Caribbean, load up cargo or kidnap slaves or whatnot, and then creep across the map, pausing in each space so that other players have the chance to play a card that will interdict your fleet. “Curaçao… Port Royal… Roatán… Tris Island…”

If you return to Europe before anybody interdicts you, great. But when interdicted, this buildup hits with all the impact of a wiffle bat. Combat is resolved via a rock-paper-scissors card system that sees the interdicted player either fleeing, surrendering, or maybe duking it out with their piratical opponent. Ties are broken by fleet size (maximum: three) or via a letter-based seamanship rating printed on each ship card. Hopefully you’ll secure a ship with an early alphabetical rating. Otherwise you’re consigned to a life of fleeing from better sailors. There’s room for treasure-burying rules and various types of ships with their own interactions, but not for engaging combat. It’s a big letdown from the granularity elsewhere.

Pax Hispanica is… well, you can guess where I stand. For years, a new Pax was the subject of much excitement in my home. Now, between the shoddy production and the seeming absence of any pushback to Eklund’s worst design and history-modeling tendencies, it’s hard to regard this thing with anything other than muted sadness. As a historical model, it’s broken. As a game, it’s a ruin.

Also, to get in an image of Shirley Bennett exclaiming, “You can excuse racism?!” — it’s boring. Just a big bore. A real snooze. Tranquilizer in cardboard. More than once, I’ve watched my co-players kingmake somebody just so we could play something else. Worse, I couldn’t blame them. If that isn’t telling, I don’t know what is.

A complimentary copy of Pax Hispanica was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my second-quarter update!)

Posted on July 31, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Ion Game Design, Pax Hispanica. Bookmark the permalink. 7 Comments.

wild. I haven’t even read the review yet but I recently started watching the Hornblower series and am on episode 4 as this came into my Inbox.

Nice! Horatio Hornblower is one of my favorite comfort watches.

ION as whole seems to have little going on to ensure their games meet a minimum playability standard. They’ve put out a couple/few bangers, but they’ve also put out games that are bad in myriad different ways.

I wish it weren’t the case, but yeah.

Yeah. ION stands out to me as a really interesting publisher, but they need to seek more wide ranging criticism on game design and thematic integration during development.

I never thought I’d see the day where you managed to fit “beefswelling” into a review, and it’s not even a Dune game! 😀

Ahaha, I’m so happy that somebody got that nasty reference!