Life in First-Person

There’s an exercise I sometimes use in class to help my students break out of their modern mindset. Everyone gets a sheet of paper and swears to avoid looking at anyone else’s work until we’re finished. Then I ask them to draw a picture of where they are in the world. To place themselves within their surroundings.

For most modern people, the reflex is to draw a map. The layout of the lecture hall, the nearby buildings, maybe our city or state or country. This isn’t universal; those with aphantasia might create rudimentary images, while my more artistically minded students sketch the nearby mountains. (Or me, sitting at the front of the class, looking more pouchy and tired than I’d prefer.) But in most cases, maybe seventy to eighty percent of the time, they draw a map. Bird’s eye view, top-down, like something you’d see on a navigation tool.

And then we talk. Because for most humans in most places and most times, a map was an impossibility. Perhaps surveyors and astronomers had created one, a painstaking process that still resulted in an unreliable thing with uncharted gaps and “here be dragons” scrawled in the margins. More often, the best one could hope for was a series of landmarks. A settlement here, a strange rock over there, a mountain or lake on the horizon. Your world was a series of visual cues, a vast maw that threatened to swallow you up the instant you strayed from its stepping stones.

This modern tendency to locate ourselves on a map creeps into our thinking about… well, everything. The identity of our kinsmen, neighbors, and rivals. The spaces that can be considered safe or dangerous. The distance between points. Our place within a country, continent, time zone, planet, ecology. Who we are.

Way more important than any of that identity junk, of course, is that maps also make their way into board games. Whether we’re talking about hex grids or squiggly provinces, nearly every board game about kingdom-building or exploration stands its players on firm footing, located safely within the confines of a perfectly scaled representation of reality.

Except for Vantage.

How to introduce Vantage? There’s the pedigree of the thing. Vantage has been a passion project of Jamey Stegmaier’s for over eight years. His included list of inspirations is a sizeable compendium that touches on games both digital and analog. The obvious touchstone, the one I’ve heard invoked most often by the game’s early players, is the recent animated show Scavengers Reign. It’s an understandable reference. Both the show and the game feature curious ecosystems and crashed spaceships, creatures and flora that might be beneficial or deadly, worlds that beckon to be understood. Tonally, though, they’re opposites. Vantage is about survival, at least in part. More than that, though, it’s about finding your place in this world. Along the way, perhaps it’s about finding yourself as well.

Finding things is the heart of Vantage. So much so that Stegmaier avoids the usual anachronisms. There are no maps in Vantage. Or, well, there are, but they’re inaccessible to you, an astronaut who has crash-landed on this science-fantasy world. Certainly maps are not the default perspective. Instead, your view is limited to first-person glimpses of the terrain. As soon as you step from your pod, you’re presented with a landmark. Pillars of stone. Stampeding animals. A caravan wending its way along the lip of a canyon. These vistas may be described to your fellow players, but never shared directly. Like a thousand explorers before you, the best you have to describe these far-off places is your words.

What do you see? That’s the question that’s asked more than any other. I see a bluff over a lagoon, covered in lotus blossoms, contrails and birds prominent in the sky. I see a covered pavilion, tarp red and flapping in the breeze, Mediterranean but alien as well, floating islands bedecked with sails in the distance. I see a child, fishing, his legs kicking in the stream. I think it’s a child. But I won’t know unless I speak to it.

There’s a beauty to getting lost, especially within the safe circle of a game. Vantage understands that. This is a game where a group’s natural first objective might be to link up, to find one another. But it’s also a game where your navigation depends on glimpses and descriptions. More than once, one of my fellow explorers has stumbled onto a landmark that I had viewed only minutes earlier. Like vessels under cover of darkness, we had slipped past one another, reaching out but never brushing fingers.

There are other ways to talk about Vantage. This being a board game, there are board game rules and board game components. The usual accoutrements.

For example, I could spend a whole review talking about the action system. All those locales — and many other cards as well, a detail I missed in our first session — offer a suite of possible actions, divided across six archetypes. One of those archetypes, the blue one, is movement. So whenever you see a blue bar, this tells you that it’s focused on movement, getting around, changing your position. But within that archetype, there’s a huge range of possibilities. One scene reveals a skeleton half-buried in the muck. There, the movement option is “hide.” Another reveals perched stones, like cairns but half a mile high. Here, one can “climb.” Elsewhere, a golden spider struggles within the branches of a tree. The movement option is “leap.” Leap where? From the tree? To the tree? Away from the spider? There are fuzzy spaces in Vantage. We will return to this.

When you settle on a course of action, somebody flips to the corresponding storybook. There are six in total — no, eight — one for movement and another for helping and all the rest of the possible archetypes, plus a couple more for actions that are harder to discover. Unlike other storybooks, those found in titles like The Elder Scrolls: Betrayal of the Second Era or Lands of Galzyr, which unfurl their stories in paragraphs, Vantage offers sentences, often as little as one or two, along with a difficulty rating. This is how many dice you’re required to roll, with higher numbers being more dangerous.

Crucially, though, there’s no such thing as failing a roll. Sure, a roll can cause setbacks. Your goal with the dice, broadly speaking, is to minimize fallout. Your astronaut has three types of health. Various results can tick these downward, bringing you a little bit closer to ending your session. So you reduce the number of dice required for a check by spending tokens, or store excess dice on your grid, or look around the table to see if any of your fellow adventurers have those precious lightning bolt icons that mean they can talk you through a problem over the radio.

No matter the outcome, though, you succeed at your chosen action. This is unexpectedly brilliant. It keeps the storybooks trim, for one thing. But it also breeds a certain expectation. There’s no need to sit in a location trying to repeat an action for three rounds. You will succeed. It’s just that you might suffer some bruises, whether to your body or your ego. Rather than wielding luck as a weapon, here luck is a spice. Even high-risk actions are worthwhile, even if they should be undertaken cautiously. There’s room to tinker, to stretch beyond your comfort zone.

And, yes, at times there’s that aforementioned fuzziness. Normally, you’re only allowed to take one action per card. How do you mark this? You don’t. Your Darwin-given memory must suffice. Sometimes another skill check will reference an earlier one. “This roll is difficulty [6] unless the wyvern is no longer a threat, then it’s difficulty [1].” Have you removed the wyvern as a threat? There are no keyword cards, as in Ryan Laukat’s Sleeping Gods. Not only does Vantage strip away the maps, thereby forcing you to rely on your eyeballs and inner compass, it also asks you to fill in your own narrative blanks. What does it mean to “leap”? What do you think it means?

In some cases, this riddles Vantage with non sequiturs. In our first session, I stumbled across a blueprint item. When I unfolded the thing, I was given the option to build a structure. I chose a stable, popping the thing into existence across some uncertain duration of time. Now I could entice fellow travelers to use my stable. The only problem was that I had no animals. So, instead, I turned into a stable-owning conman, inviting wanderers to take a gander at my very clean stable for a credit a pop.

Now, this entire sequence could charitably be described as incongruous. While I settled into the life of a stable-owning crank, my fellow players were having adventures that seemed to only require minutes or hours. Even leaning into the powers of my own imagination, the story was straining at its boundaries.

Fortunately, while this illustrates where some of Vantage’s seams show through the stitching, it was an exception rather than the rule. But it does speak to the proper mindset for experiencing this thing on the table. Vantage is all about the ride, man. It’s about going on a journey and not worrying too much about where you wind up. This is the foremost reason why I balk at comparisons to Scavengers Reign. Here, even survival is often a secondhand concern. Sure, there are lengths you’ll go to in order to keep your health trackers from dipping too low. But even failure, when you flip to the corresponding page, outright asks if you want to end your session or accept a bunch of extra health and keep playing. On the chill scale, that’s pretty darn chill. Vantage is for vibin’.

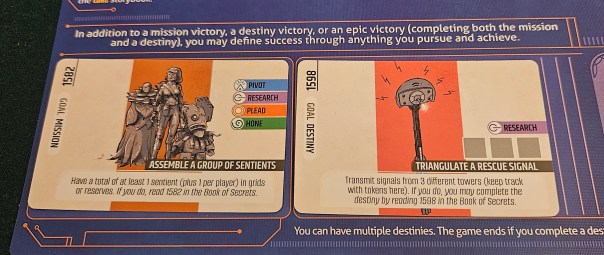

That same coziness extends to your objectives. When your characters arrive on the planet, you obtain a mission. Maybe you’re here to steal a valuable item in one final heist. Maybe you want to develop your skills as an explorer. Or maybe you’re hoping to assemble a squad of sentient buddies to really make a splash at the disco.

Over time, though, it’s possible for your mission to take a backseat to a destiny. These cards are found as you play. Perhaps you’ll discover a way to send out a distress signal, prompting your crew to begin the hunt for transmitters. But it’s just as possible that you’ll decide to settle down and open your own shop, tame a dragon, or become the local Gwent Skirm champion.

These alterations work so well because of Vantage’s self-contained nature. When the original Sleeping Gods came out, some players were disappointed to discover that their adventures were on the clock. At the time, I argued that this was necessary to give the world its stakes. Vantage works in the opposite direction. Rather than functioning as a campaign, Vantage is played in single sessions. These can take a while. Our longest was four hours, although most of them have been closer to two, and we could have opted to conclude sooner. But this permits a narrative arc to blossom and perhaps fluctuate within the span of a single sitting. Your astronauts stagger to their feet, learn to survive and then thrive, and perhaps change their minds about why they’ve come to this place. In finding their place, they find themselves, too.

For all of Vantage’s many clever touches, the moments that take my breath away are those that illuminate how your adventurers position themselves within the world. Or perhaps more accurately, how incredibly difficult it can be.

I remember the first time I took to the skies. I had recovered some sort of vehicle that lifted off the soil. Suddenly I was subjected to hypoxia, my health bleeding away for every turn in the thinner atmosphere. As systems go, this was a smart way to prevent me from floating around too long. But in those stolen moments, oh, to see the world from on high! The same landmarks I had investigated up close were tiny now, some obscured by clouds, but their relative position so obvious now that I could see them as they were.

Or that first time I was shown a map. Some passing sentient let me take a glimpse at the paper in his possession, little marks denoting the placement of some artifact or another. For all of thirty seconds, I felt like Hillalum from Ted Chiang’s “Tower of Babylon,” witnessing the shape of the world for the first time. I won’t spoil what I saw, but it reminded me just how paradigm-shattering a good map can be, reorienting my perception in an instant.

Or there’s sea travel. There are oceans on Stegmaier’s planet, just as there are deserts and tundras and everything else. But rather than traveling in straight lines, certain passages buffet your character with currents and winds. More than once, I’ve voyaged along what seemed to be a straight axis, only to be pulled to parts unknown. Ancient mariners hugged the shore and only rarely risked open waters. In Vantage, the seas are the realm of the unknown. Here be dragons.

Or there’s the time my sister-in-law got trapped in a tunnel for forty minutes, looping back on her previous position, hopelessly lost. Or the time I spent a whole-ass hour squatting outside a magic academy, straining to learn magic spells like the world’s most mana-constipated loser. Or the mushroom who became my best friend. Or the time another player heisted a mech suit from some cyberpunk city, then crafted it into a rudimentary spaceship. Or or or—

There are entire worlds here. Small but dense worlds, multilayered and full of wonder.

Those worlds hold meaning because they’re placed within reach, if only barely. Laid out side by side, the planet would feel small and meager. But that isn’t how the world is presented. Up close, every corner hides something new. At times, that newness makes Vantage feel undirected, one random happenstance befalling your astronaut after another. If this game is a tapestry, you’re only offered the threads.

But that’s also what makes Vantage special. This is a game about taking up those strands, following wherever they may lead, and maybe catching some glimpse of the larger whole — a sparkle of gold here, the outline of a symbol there — but not, until many sessions have passed, many characters, understanding their larger import. To play Vantage is to inhabit, for two or three hours, the limited perspective that is our birthright, robbed by cellphones and highways, to wander and seek and find. To learn the shape of things. To become the landscape.

A complimentary copy of Vantage was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read the first part in my series on fun, games, art, and play!)

Posted on June 26, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Stonemaier Games, Vantage. Bookmark the permalink. 15 Comments.

Fascinating. Doesn’t sound like my kind of game. How does it compare to Earthborne Rangers?

There are some strong parallels between the two, as you might expect. Within a single session, Earthborne Rangers is more about navigating its little ecosystems, struggling to survive or accomplish your objective. But while you’ll travel afield, eventually crossing three or four territories in one sitting, it tends to limit its scope to those handful of decks at a time. The single-session nature of Vantage means you spend quite a bit more time traveling. And, as noted in the review, there’s really no “struggle to survive,” as such. You can lose health, but this is more of a session timer than anything else. In a sense, Vantage feels zoomed-out, while Earthborne Rangers feels zoomed-in. I love them both, but they wind up producing very different types of exploration.

What an evocative, lovely description of this game! I’ve eagerly followed the various designer diaries and glimpses into what Vantage has to offer, and I am excited to play in this world.

I deeply appreciated your words, to learn the shape of things. That resonated with me and made your experience with Vantage palpable. Much of my life is directed to help others make sense of complexity or navigate ambiguity–to learn the shape of things.

Cheers.

Thanks for reading!

thank you for this! it’s fun to see a more.. i suppose niche isn’t the word, but maybe divisive game from stonemaier. seen a lot of “this is not for me at all” and equal amounts of “this game was hand tailored for me”. i’m far more in the latter. super excited, a lovely read as always.

Thanks for reading, and I agree. I like much of Stonemaier’s output, but this is probably the most impressed I’ve been with one of Stegmaier’s personal designs.

You had me at Hillalum! One of my favorites of Chiang’s superb short stories.

Mine too! So much, in fact, that “Tower of Babylon” really kicked my butt into gear to write a short story that had been rattling around my head for like five years. And then, somehow, it got published a few years back! Thanks, Ted Chiang!

insta-purchase.

http://aanpress.com/aanorder.html#neverisearth for those who are interested

Wow, I wasn’t expecting that! I sincerely hope you enjoy it.

Extremely thankful for this review. My usual instinct, with both Stegmaier’s games and storybook games would be to ignore them out of hand, the former for general blandness, the latter for tendency to be a bunch of tedious filler between a handful of good parts (which is gameplay and which is storybooks varies from person to person).

But Vantage really has something special, it delivers on the fantasy open world video games promise much better than anything I ever played, digital or cardboard (except perhaps Caves of Qud). Would have been my favorite game I tried in 2025 if Guards of Atlantis 2 didn’t exist.

I’m super happy to hear that! (And yeah, GoA2 is pretty incredible too.)

Pingback: Space-Cast! #49. A Vantage on Vantage | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Vantage (2025) - Un monument ludique ! - Le journal de Jarjar

Pingback: Best Week 2025! Picture Perfect! | SPACE-BIFF!