Cyclades Nuts

Cyclades. Now there’s a name I haven’t heard in a long time.

Except, of course, I’ve heard it plenty. How could I not? Cyclades, along with Kemet and Inis, was the first member of Matagot’s unholy trinity, the gods-on-a-map game that urged the genre in a new direction. Without Cyclades, there’s a reasonable argument to be made that there would be no Blood Rage, no Ankh, no renaissance of plastic figurines murdering each other, but murdering each other via modern tabletop mechanisms rather than just rolling dice, Risk-style, hastening the genre’s gradual decay into obsolescence. Cyclades was the pantokrator that filled the form’s lungs with new breath.

It’s also an essential strand of my own gaming DNA. My review of Kemet was one of the first to draw any attention. Inis is still possibly my favorite game of all time. And before those, there was Cyclades, experimental and bold, off-kilter in its own way, a little imbalanced, but always gripping.

And now Bruno Cathala and Ludovic Maublanc have a Legendary Edition out. Over the past month or so I’ve revisited the classic, partaking of its deified air once more — and also marveling at how far game design has come in the intervening sixteen years.

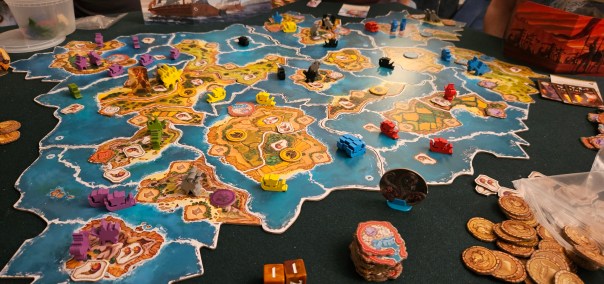

For those among us who are new to the scene, let’s arrange some furniture. Cyclades is a winner-takes-all smash-’em-up between two to six factions of Greek island-hoppers. Your objective is to found three metropolises, a very city-state way of conceptualizing victory. Along the way, you will recruit armies and navies, bridge the gap between islands, and seize territory that you will then defend like it was your very own homeland. Metropolises can be built one structure at a time, stolen from rivals, philosophied into existence by gathering enough gray-haired thinking men — see Dad, I told you my humanities degree would be good for something — or carved into the landscape by a hero’s glorious sacrifice.

Regardless of the method, founding a trifecta of ageless city-states will take some mettle. No moment is without risk. Conflict either lurks around the corner, ready to flip you upside-down and shake the change from your pockets, or else it’s in your face and already delivering the shakedown. Winning usually means bruising some friendships.

At heart, though, Cyclades isn’t as straightforward as most images might make it seem. At the time, it was billed as “dudes on a map plus something else.” Later, Kemet would have its pyramid action-selection system, Inis its card-drafting round. For Cyclades, its “something else” is an auction system for currying the favor of the gods. And let’s be honest, the game revolves around the auction more than around the actual positioning of dudes, monsters, and gods. The Legendary Edition tweaks the balance somewhat, putting its finger on the scales to tilt affairs back toward direct conflict, but now we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The gist is simple enough. Each of the game’s seven gods offers a distinct boon. Ares lets you recruit and move soldiers, making him the default god for warfare. Huh! Appropriate! Poseidon does the same but for boats. Zeus is all about those temples and their priestesses, both of which save cash in some way, making him a necessary visit for anyone who intends to win future auctions or stock up on monsters. Athena initially seems like a losing proposition, offering philosophers and universities, but those offer a turtle’s path to victory by turning out metropolises that don’t require bloodshed. Hera lets you recruit mercenaries or build any structure at all, effectively giving the runaround to the other gods. And last and certainly least, Apollo strums his lyre — for some reason he’s always strumming a stringed instrument rather than rocking the aulos — providing a couple of measly coins and improving your income. Until somebody comes along to steal your drinking money, that is.

What makes this auction so important is that nothing in Cyclades happens on its own. Winning a god’s favor provides access to their boons, but only theirs and nobody else’s. Mounting an invasion, then, isn’t as easy as hiring some troops and pounding the beaches of a rival’s shores. Instead, it looks more like this:

(1) Parlay with Ares to recruit loyal soldiers.

(2) Persuade Poseidon to grant your ships safe passage, making a tenuous chain of vessels between your island and your target.

(3) Oops, now your target keeps outbidding you for Ares as a defensive measure. Now bid on Zeus a couple of times so your new priestesses will make it easier to win future auctions.

(4) Run out of money. Hang with Apollo.

(5) Since nobody has bid on Athena this turn, go ahead and win that auction for zero Greekbux. Her mercenaries will give your invasion force some oomph anyway.

(6) At last, you can bid on Ares and win! You prepare your invasion. Except…

(6b) Somebody earlier in the turn order has sent the Kraken to eat the fleet needed to ferry your troops from one island to the next.

Repeat.

For newcomers especially, this can make Cyclades seem static, closer to trench warfare than open seas. Don’t be fooled. To quote Julius Caesar, who was not Greek but, look, we’re in the general vicinity here, experience is the greatest teacher. Much of the game’s strategy is about choosing your battles, eking out advances that will bring you closer to victory without bringing a rival’s wrath down on you. Because Cyclades is also deeply given to revenge. Rob somebody of their position too totally and there’s nothing to prevent them from dedicating the next hour to returning the favor. With careful positioning, the right auctions, and some diplomatic tact, this is a game that’s possible to play well.

And, of course, there are the monsters.

Nowadays it’s almost a given that these things will include big chunky monsters, but when Cyclades first manifested it was a major selling point. The monsters are… well, look. People have differing views on the monsters. Cyclades occupies a middle ground between Kemet and Inis in this regard. Some monsters are big beefy boys who stride across the map, contributing to battle or possibly just chowing down on anything in their path. Others offer one-time abilities that can alter the course of the whole war.

In both cases, the monsters are game-changing and completely, entirely imbalanced. To be clear, I don’t put much stock in balance. But there comes a point, usually around the final act of Cyclades, when everybody is going to be hunting for the Pegasus. If the Pegasus has already been played, then your goal will be the Chimera, because the Chimera can drag the Pegasus out of the discard pile. If the Pegasus hasn’t appeared yet, then Zeus is your god, because Zeus can peek at two cards from the top of the monster deck and recruit one.

This whole rigamarole is because the Pegasus lets you teleport an army from any one location to any other location. Provided you hold two metropolises, that winged bastard is basically the win button. To be sure, this being Cyclades, there are disruptions aplenty. Recruit more troops. Steal your opponent’s mercenaries with the Giant. Harry the invader with a Harpy. Lock down the whole invasion force with Medusa. Flip the table. You know. Disruptions.

Unlike some people, I don’t think the Pegasus is a problem. If you know the Pegasus is coming, that’s where the game gets interesting. It’s possible to chart out your auctions more carefully, deliberately picking a god who will resolve earlier so you can buy the Pegasus first. Or maybe use a rival’s certainty to your advantage, instead invading their islands the conventional way. In our most recent session, the victor unexpectedly captured her second and third metropolis by sea, bypassing the monster stuff altogether. While everybody else was focused on their shiny toys, she was building ships and conscripting teenagers.

While I don’t worry too much about the Pegasus being a game-breaker, it does function as a harbinger of Cyclades’ more persistent issues.

Some of these are countered by the Legendary Edition. The map, for example, is no longer a single static board, but a modular playspace that produces both tiny islands and sprawling… well, they’re still islands, not anything like continents or peninsulas, but they’re still big enough for multiple factions to march across. This gives the game a more open feel than the original, letting both navies and land armies shine. There’s more jostling for space than before, a greater focus on actually smashing armies into each other, and it feels great.

But other alterations are mixed. Such as… the map! Previously, metropolises could only be built in dedicated slots. This prompted players to race not only for the necessary structures, but also for the scenic cliffsides that could comfortably house their Athens. Now that metropolises can be built anywhere, there’s more incentive to hunker down in your own corner, bristling with defensive fortifications and troops. Which, while a valid approach to victory, is rather dull.

Other changes are similarly textured. Previously Ares was critical, being the only god who raised and moved armies. Now any member of the pantheon can move armies, provided they’ve had Hera recruit a hero at some point. Heroes are an intriguing distinction from the original game. Like monsters, they add abilities to the table, and can even be sacrificed to trigger some ultimate power. Odysseus cheats by building a metropolis from three buildings instead of four! Hector murders anyone who invades his space! Perseus is basically a new Pegasus! But while sacrificing a hero is tempting, they’re most valuable for their ability to move and attack at almost any moment. Cyclades has never been more dangerous.

Along the way, it loses some of its original texture. This new Cyclades is breezier in all respects. The map is more dynamic. It’s easier to move armies into engagements. The auctions aren’t quite as hidebound as before. Even the playtime has been reduced, the race to three metropolises closer to a hundred-meter dash than a marathon. Now there’s a Greek reference.

At the same time, that ease also brings its own frustrations. Security is harder to obtain than ever, introducing high drama to the endgame but also making success feel more mercurial. (I guess I should say “more hermetic,” since I’m being all Greek about this, but hermetic means something else. Oh well.) Instead of the original game’s singular Pegasus, it now feels like there are three or four pegasuses, any one of which can be blocked, but taken together present a far more tangled path. The game now has a shade of the Munchkin Problem. Victory doesn’t belong to the player who springs their trap first or cleverest, but to whomever springs it once everybody else has run out of their own traps.

To be clear, I’ve had a wonderful time with Cyclades: Legendary Edition. I wouldn’t call it inferior to the original. Its improvements are real and numerous. But so too are its deviations, some of which usher the game along uncharted paths.

This uncertainty speaks to the fuzziness of new editions. The Legendary Edition is closer to a reimagining of Cyclades than a remake, familiar but also new, like the Final Cut of Bladerunner or Cole Wehrle’s second editions of Pax Pamir and John Company. In its most faithful moments, it recaptures what caused the original game to launch a hundred imitators. At the same time, here’s some truth: this isn’t the right pantheon for being faithful.

In the end, then, the Legendary Edition is a formidable, but also altered, version of Cathala and Maublanc’s classic. It’s something you might find in a museum, but all plastic and jangling lights, pushing buttons rather than peering through glass or, better yet, getting your hands grubby in the dirt. I still prefer Kemet and Inis. Still, it’s nice to take a look back along the family tree and be reminded that its roots run deep.

A complimentary copy of Cyclades was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read the first part in my series on fun, games, art, and play!)

Posted on May 28, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Cyclades, Open Sesame Games. Bookmark the permalink. 23 Comments.

Inis really is a masterpiece — probably my favourite game of all time too, and I’ll admit to no small gratification that my favourite critic esteems it so highly!

Cyclades-wise, I’ve always been tempted by the theme but my group really shies away from direct-warfare troops-on-a-map type game (and in fact, one player hates anything even CLOSE to that to the degree that she won’t play Inis, much to my chagrin). If this edition had been an all-cylinders-firing slam dunk, I might have still picked it up, but the description of the endgame here just doesn’t sound appealing to me.

Yeah, I think that’s where some diehard fans of the original will land, too. I never loved Cyclades as much as Kemet or Inis, so the downsides don’t bother me in particular, but I think they’ll rub some folks the wrong way.

Thank you for the review, I want to try this one out. When you wrote “This uncertainty speaks to the fuzziness of new editions”, it reminded me of Innovation Ultimate edition having the same issue. It sped up the game by letting you skip entire ages, but that also made the game less deliberate than the third edition.

But I guess at least people have the option of what kind of game they want. Maybe modern audiences are changing, but I think I still like the “slow cooking” of experiences.

I hope you get to try it! My policy on everything is always “try before you buy if at all possible.”

This may be your most inspired blog title yet. Truly masterful [chef’s kiss].

I am an artist.

genuinely made me snort-chuckle.

Oh my god I read this a week ago and completely missed the title.

You ARE an artiste of the highest order sir.

Haha, thanks.

Great review as always! One reason I’m particularly excited for the edition is just a singular version that includes at least what the designer feels is the “best” edition of the game after producing numerous expansions (big and small) – the Blade Runner allusion is appropriate. There are countless debates on BGG about the “best” way to play Cyclades, and from what I remember it was something like a little from this expansion, and a little from that expansion, remove a couple cards, etc.

I don’t think this game will completely end those debates, but it should make getting the game to the table less of a nuisance than I’d like. I had brought the game (with expansions) to one of our annual game retreats, and it took me at least 30 minutes sifting through all of the expansions to try to set it up in the “best” way possible, as well as making sure I understood all the rules from the various expansions (made more difficult by choosing to be free of any text and heavy on somewhat confusing symbols).

Ironically, I kind of see this happening with the currently-funding Inis big-box. The first expansion already has a couple modules, one of which I ignore, and the new expansion adds a couple more. I guess there is some freedom in choosing which ones work best for your group, but it front-loads some decision making before the game is even tabled!

I definitely agree on that count! I never played the expansions to Cyclades, but I’m feeling that pressure when it comes to Dune: Imperium, so a curated box certainly makes sense. Thanks for sharing your perspective!

This right here! As someone who has played with all the expansions, I really do think this is a ‘greatest hits’ version. The only aspect I don’t love is the modular map, because it seems unnecessary and is kind of a PITA to set up. The Titans map seemed functionally the same without the hassle, and I don’t think the modular variability really adds much.

To Dan here, the part you seem to have glossed over is the SIX PLAYER GREATNESS. Not many games in this vein support six players, which for me is a huge selling point.

My only other gripe (which retail owners won’t experience) is that some of the Kickstarter heroes/monsters seem a bit half-baked, and are an instance where more seems to be less. I may take them out.

The count variability is definitely a plus, good point! And it scales well at more or less any count, too.

Played Legendary twice, previously have played my original + Titans expansion at least half a dozen times. After the two games my thoughts were Legendary was largely better, but thinking about it more I’m not so sure anymore. I thought to myself, did I ever really have to rearrange my ships, or do the new sea spaces mean freshly placed ships create adjacency without movement? And that got me thinking about all the other tweaks in the game and if they really affect my enjoyment of the game at all. I have to go back to the original to know for sure.

But most of all, the boxes for my old versions of Inis, Cyclades, and Kemet match each other, they look so nice together on the shelf. I can’t just break up a family like that!

I definitely agree that it feels more like a reimagining, doesn’t look like it on the surface but it absolutely feels different. But not like it’s a different game, more like if my sister remodeled her home and moved all the rooms around.

Right, I think Poseidon gets a minor debuff here. Which isn’t all bad — previously the guy was a tyrant! And with those income-generating spaces there’s still reason to fight over the seas. It’s just not quite as critical as before.

I find myself tempted by the new Inis, but also reluctant to swap out my original box. We’ve been through so much together!

Cyclades remains my favorite of the Matagot mythological trio (as opposed to Eric Lang’s mythological trio.) Like you, I don’t put much stock in “balance” as, the vast majority of the time, I’ve found that people complaining about it either a) haven’t played enough to really assess it or b) have played the same way, keep losing, and blame the game for it. Some games suit some people better than others.

I didn’t get in on the Legendary edition because I have everything for the original, down to the Kemet crossover monster cards. I appreciate some of the changes that they’ve made, but many of those changes were already included in the various expansions; not least the map of Titans enhancing that sense of area control that you mention. But also things like Hades creating another route for military action (which Titans also does) and small additions like Monuments changing the makeup of that static board by allowing for more powerful structures to be battled over.

All of that to say that I think it’s still my favorite, despite my high appreciation for its two siblings and that I’m both glad to see your usual measured perspective on it and that it’s been reintroduced to a new generation.

I reviewed the Kemet/Cyclades crossover cards ages ago! What a blast from the past.

That title, a true master wordsmith.

I love my Matagot collection of all three games taking up a single shelf. While Inis is my favorite, Cyclades is some wild fun. I’m happy to keep with my original version and pick up the new Nemed expansion (legacy version) for Inis instead.

Huh. Thanks for informing me that I was mispronouncing the first and second syllable of Cyclades. Fortunately, I was pronouncing the third so the title had the desired impact immediately.

Now I’m interested to hear how you were pronouncing it! The one I usually hear is psy-CLADES. Which, it goes without saying, does not work with this article’s title.

Sigh-Clay-Deez. I knew the deez because… no idea. Because I read The Oddyssey? Because I had friends growing up who were the children of greek immigrants? No idea.

That’s really close! Definitely closer than sigh-clades. If you have some basic knowledge of Greek, I can see how you’d get there.