Love and Heartbreak in Georgian London

As a second-grader, I despised recess. Not because I enjoyed class — it was boring and tedious, hemmed in by schedules and busywork — but rather because I was lonely. Some people don’t understand loneliness. They can’t. It wears the soul to a grainy powder. I had recently changed schools, bidding farewell to my friends and those familiar halls. Now I spent those interminable minutes wandering the lawns, balancing on the rocks, avoiding the bullies I half-knew from church.

And then, like the sun warming my face after a chill, there they were. Two friends. Adam and Adam. They invited me to play make-believe with them. We soared across the grass, scraped our knees together, became soldiers and explorers, scared ourselves silly at sleepovers, told our first dirty jokes. Once, afraid that I had done something that would make them abandon me, I burst into tears, only for both Adams to enfold me in a gangly, childlike hug, reassuring me that all was okay.

Everything was bright. For a time.

Molly House, designed by Jo Kelly and Cole Wehrle, tells the story of 18th-century Londoners who risk everything — reputation, dignity, fortunes, even their lives — in their pursuit of companionship. It is a game about the human yearning to discover people who would witness us at our most vulnerable, for life partners who would embrace both our potential and our frailties, our sex and our illnesses, who will become willing lovers and caretakers. The words have been repeated so often in our films and literature that it’s easy to forget their origins in the Book of Common Prayer and the Sarum Rite before it: “For better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love, cherish, and obey, till death do us part.”

For those who fit the mold, finding one’s place in the world is rarely easy. For these particular people in this particular place and time, that prospect is even more fraught. Where most of us face rejection or embarrassment, their rejections might well lead them to the gallows. These are mollies — sodomites and buggerers, to use the sweeping terminology of the time — and they do not fit into the slender conception of manhood that dominates the London of their day. They are not only despised but actively hunted, the Society for the Reformation of Manners seeking to entrap and arrest them for the moral good of the city.

To play Molly House is to keep one eye on your friends and another on the door. In its revelry, there is always danger. The suits of its deck become potential evidence. The appearance of a face card elicits a little thrill, suspended between terror and elation as everybody leans in to see whether the figure in the doorway is a molly, here to conduct the festivity for people such as yourself, or a constable, cane raised to crack your forehead. This is a game about joy. Hard-fought, stolen, desperate joy.

When I wrote about an earlier build of Molly House a year and a half ago, I was struck by the determination of that joy, its resoluteness. This is the first big publication from Kelly, but Wehrle is no newcomer to designs that emphasize imperial violence, whether the adventuring armies of Pax Pamir, the empire-toppling merchants of John Company, or the opium-slinging traders of An Infamous Traffic. The violence in Molly House is of a different stripe. It’s a Sword of Damocles rather than a cavalry saber. But it’s there all the same, suffusing the experience with anxiety.

In the intervening months, the game has transformed. As before, most turns are simple, but the method underlying them has changed. Players roll two dice to determine how far they can move. This is more flexible than it might sound. Movement allowances hew closer to Talisman than Monopoly, your gentleman journeying either clockwise or counterclockwise. Moreover, you are free to use both dice together or only one of the pair. Often, this affords plenty of room to pick your destination.

But not always. In some instances, your pawn won’t be able to land where you would prefer. It’s a small thing, but it’s a reminder that limitation is a potent tool in any designer’s kit. As much as you might want to stop at a particular garden, or swing by that special store, or visit the molly house today, it’s a reminder that forces beyond your control conspire to prohibit your movements — both physically at the table and within the society playing out in its imagined space.

The result is a measured motion, always cautious, always inspecting where one is permitted to go. This prohibition extends to the spread of actions available to you. It’s always possible to lie low — to draw blindly from the deck, itself a risk. More often, there’s value in “indulging,” selecting a card from the game’s market that matches the suit of your current space. Or, if you’re willing to accept some risk, you might go looking for people like yourself. Just as 18th-century London contained arcades that were known as places that someone could solicit company, your pawn can cruise these destinations. There is potential here, letting you draw many cards at once. But danger, too, as the prospect of stumbling across a constable or rogue increases with each draw.

The centerpiece of the design, and the reason for all those accumulated cards, is the festivity. These are only permitted when you visit a molly house, one of the destinations at the board’s corners. This is the main way you will score “joy,” the game’s label for victory points, but it’s also another opportunity for unwanted exposure and attention from the constables.

Where movement across London is restrictive, festivities are wellsprings. Everybody is invited, everybody may contribute. The objective, broadly speaking, is to build a hand of four cards, representing the acts performed by your protagonists in the safety of the molly house. As a game, Molly House is tasteful; these acts are never spelled out in detail. Instead, they are relegated to the four suits and brief descriptions. Perhaps you will hold a surprise ball, playing four sequential cards in one particular suit. Or maybe a molly will appear — a queen or jack — to permit a lesser festivity, such as gathering three additional similarly ranked cards or a run of three non-matches. When everything has been played, including at least two cards from the top of the deck that represent other attendees beyond your immediate circle of acquaintances, the best hand is tallied. Anyone who contributed a card to that hand earns joy.

These festivities are vigorous and exciting, offering a grand opportunity to churn your cards into points. But they are far more than that. Play your cards right and you can show up your fellow players. As I noted, only the best hand will score. This lends a certain cattiness to the proceedings, not unlike the sniping that occurs in any Austen novel. It’s entirely possible to host a festivity under the assumption that your modest hand will permit, say, a dance. But as your fellow sojourners stop by, perhaps increasing the card pool with a splash of gin or drawing outsiders into the party with the fiddle, a party might spin out of control. Now it’s a mock christening! Your cards aren’t scoring even though you’re the host! And look here — a constable!

This last possibility is the cracked capstone that keeps the festivity from true security. Constables pose a constant threat, as do rogues. The former collect evidence on the party’s attendees; the latter are members of your community who might present real trouble if not satiated. Fortunately, either can be placated if you host a quiet gathering rather than a grand bash. Of course, that isn’t entirely within your control. More than once, the table has conspired to throw the constables off our scent by hosting a dignified party, only for some ill-timed random cards from the street to strike up the band. Such moments are dizzying both in their comedy — Molly House is a profoundly funny game at times — and in the panic they trigger.

The intrusion of the Society for the Reformation of Manners casts a pall over the celebrations. It isn’t uncommon for the game’s first round to be intoxicating, everybody collecting cards and throwing parties, heedless of how much attention their revelry attracts. This is the warm glow of a new relationship, that brief period when even one’s childhood seems overwritten by the exhilaration of something new.

But then the round concludes and the cards in the gossip pile are tallied. Constables and rogues that were dismissed from the market or lingered in player hands too long, plus any cards that didn’t score in festivities, are transformed into potential evidence against your revelers. Little by little, the houses on the board’s corners are imperiled. Eventually, one or more of them will be raided. And when this happens, Molly House turns a corner.

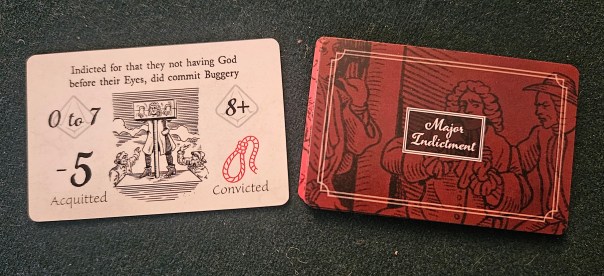

Around the bend, there is still the potential for joy. Until the last of the molly houses is shut down, the glimmer of hope that marks those early moments is never fully thrown into darkness. But the festival atmosphere does grow more muted. Depending on your reputation, the raiding of a molly house may result in an indictment. These pose an indignity that will be familiar to anyone who cursed the retirement rolls of John Company. When the game ends, acquittal is possible, although it will still diminish your joy. Conviction, on the other hand, will reduce your score even further — and may thread your character’s neck through a noose. In other words, your fate is once again cast out onto the streets to be determined by a mere roll of the dice.

However, your indictment is not yet put into effect. Instead, the constabulary offers you a deal. Either face the indictment or turn informant. This smudges the proceedings. The earlier festivities were always semi-cooperative. Your objective was to score the most joy by the end of the game, along with enough joy for the “house” to create a lasting community of like-minded fellows. Now, though, somebody may be working against that very community. Somebody in the parlor, at that very table, could be gathering evidence against the group. They have become the same rogues that needed to be treated carefully when they wandered into a party. And while you are free to accuse one of your fellows and reveal their face-down token, transforming them into pariahs if your guess happens to be correct, this is not an action undertaken lightly. This hidden community knows all too well the perils of a loose tongue.

Historically, this is what destroyed the best known of the molly houses. Mother Clap’s was brought down by an informant. Three customers were hanged; Margaret Clap and a handful of her associates were pilloried and imprisoned.

In one light, this dampening of mood comes across as an unwelcome intrusion. Molly House is a celebration of queer joy, of the relief of finding companions with whom one is safe and accepted. Last year, I wrote about attending a game night for gay men, how I was welcomed into their home and shown such acceptance that it left me shaken. Not everybody understands what it means to escape loneliness, whether because they have never been truly lonesome or because they have yet to find acceptance. To play a game that extends its hand only to snatch it away, or at least to make one wonder at the offered hand’s intentions, is borderline cruel. Perhaps it doesn’t help that Molly House’s simple rules are also intruded upon, viciously complicated for those who turn traitor. In short: no more joy. Only the possibility of survival.

But this is also an essential part of the telling of queer identity. I don’t consider myself queer, but I have experienced the terrible loneliness that follows in the wake of companionship. I remember urinating with one of the Adams in the gully behind my house, when suddenly he spun and revealed his penis and forcefully insisted that I show him my own. I bolted, and locked the door to the house behind me, and wouldn’t come out until he promised to not do that again. Our friendship lingered a while longer, but it was never the same. Years later, when an older man from church had similarly revealed himself, and more besides, and I tried to express to my father how scared and confused the ordeal had made me, he thumped me on the chest and swore to have me committed if I ever talked like that again.

Even for a child like me, straight and bland and somewhat prudish, sexuality was something that could never be shared, only alluded to, elided, sidled around like a tiger seated in the living room. At times, carrying that loneliness was devastating. It is not good to be alone. When I met Summer as a buttoned-up returned missionary, I was drawn to her for a thousand reasons. But the foremost reason was that she seemed like somebody I could, at last, tell about my past without being tossed aside. I love her for her humor, her ambition, her body. But above all, for the trust she also shares with me.

Molly House is about all of these facets and more. It is about the fired coal of finding a friend, but also the flickering ember of being driven apart. In that way, it is as much about imperial power as the other titles in Wehrle’s historical oeuvre, about the way religions and states define boundaries, about how they divide communities and companions to make the task of enforcement that much easier, about how the casualties of these programs are not insignificant or unusual, but commonplace. Where John Company asked us to become bastards, and thereby understand the shambling horror of colonial power all that much better, Molly House asks us to become reluctant traitors of the self. And, hopefully, in the process, come out the other side a little more human.

More than merely operating as a rumination on imperial power, however, Kelly has crafted a paean to queer resilience. This, I think, is Molly House’s last gift. That in its dark moments, it keeps the fire. In exposing how any would-be oppressor must divide before they can conquer, it becomes not only a fine example of historical expressionism, not even only a celebration of queer love, but a statement of solidarity. Bring in the lonesome, it says. Bring in the tired, the strange, the refugee, the outcast. There is room in this house. The gin is strong and the music is whirling. Together, we are more than we could ever be apart.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read a 3,000-word overview of the forty-ish movies I saw in theaters in 2024.)

A complimentary copy of Molly House was provided by the publisher.

Posted on February 12, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Cole Wehrle, Molly House, Wehrlegig Games. Bookmark the permalink. 47 Comments.

Thank you for this amazing piece of writing.

Thanks for reading!

Seems gay

Astute!

This is such a moving and insightful piece, and I’m so taken aback by your writing. Thank you for sharing your story as part of the discussion about this incredible-sounding creation.

Thanks for your kind words!

I confess, Dan, to often skimming quickly through your posts, rushing over the humour and personal touches and insights with which you imbue your writings. THIS post however I savoured, slowly – it stuck me, and I’m not truly sure why, as one of your deepest and most personal yet. Maybe because of the descriptions of loneliness and the chords they struck with me, not really sure.

Regardless, thank you for your thoughts on the game, and perhaps more so, for sharing.

Sometimes it’s worthwhile to take it slow. 😉

This may be the most beautiful and touching board game review I have ever read.

Thanks!

Well. I did not think a piece of board game criticism could move me to tears. But here we are.

Hopefully they’re good tears and not suffering tears!

Tears of… recognition? Of the longing to belong. And tears of gratitude for having found my community and my joy. And tears of compassion for those still searching.

An astounding piece, Dan; thank you for your critique of the game and your own personal share, I’m sorry to hear what you went through and how your own father reacted.

Molly House was a game I’d backed, and had waned interest in in the time between, however your writeup has me mentally picking a group that would actually help me get this to the table.

Am now again looking forward to its receipt hopefully in the next few weeks, ideally it would be here for the weekend of the queer Mardi Gras in Sydney but chances of that are probably slim.

That would be cool! Unfortunately, I don’t know the current state of the game’s shipping…

Dan, thank you for your lovely writing, as always. I actually was triggered to come over here because I got half-way through a particularly ham-fisted review on BGG and needed a palate-cleanser. As an aside, I wonder if you would indulge me: perhaps you have addressed this in the past and I missed it, but I am bothered by the apparent discord between your writing which is very pro-queer and progressive, and your professional dedication to religious doctrines that are decidedly not. I hope you don’t mind if I ask(I’d assume you don’t) for an explanation. How do you reconcile your clearly open-mindedness with a religion that maintains some cruel beliefs. Thanks!

That’s a good question! The simple answer is that I’m not currently a practicing Mormon, so the whole issue is somewhat moot.

The more complicated answer is that Mormonism stands at a crossroads. At a certain fundamental level, its soteriology is universalist. That’s a simplistic rendering, of course, but the gist is that every person can achieve complete salvation. The elephant in the room is that some people, especially those who don’t fit within a rather narrow understanding of gender and family, are provided no clear path to salvation that doesn’t also include the annihilation of their identity. This is cruel and clashes with the religion’s universalist strands of thought.

But quite a few Mormon thinkers have pointed out that the LDS Church’s current understanding of the fate of individuals and families in the afterlife is not only limited, but highly contingent on culture. For instance, temple sealings, which are limited to heterosexual couples — and which are technically polygynous, with a man able to marry multiple wives but women only permitted one sealed husband — are only the most recent expression of that doctrine. In earlier times, sealings operated according to different modalities, such as proximity to prophets or the “great chain” theory. If this “ancient and unchangeable” practice is both renewable and changeable, well, then there’s no reason to believe it won’t change again.

In other words, there are plenty of modern Mormons who are able to walk that tightrope with varying degrees of success. Some believe that the LDS Church’s perspective on LGBTQ+ people will inevitably change, much as it did on Black members, polygamy, dietary restrictions, separatism, and other issues. Mormonism likes to think of itself as this singular thing, a Restoration of the early Christian church. Of course, that early Christian church was not one thing but many, and Mormonism is similarly not one thing but many. No matter how much its leaders might wish otherwise.

Personally, I’m trying to keep my religious traumas from boiling over into too many articles. I hated being a missionary. Church was a horrible experience for me from a very young age. Still, there are benefits to growing up Mormon. I learned public speaking and fiscal responsibility, spent a lot of time outdoors and in holy places, and was bolstered by its sense of structure and identity. I love holy books and ancient translation and history and weird literature all because of my upbringing. I even still believe in “tithing,” and wish everybody would practice considered giving. For my part, I donate not to the LDS institution, which hoards its wealth to a gluttonous degree and supports some rather spurious causes, but rather to various charities that help at-risk Mormon youth. Am I a Mormon? Sure. But that term means a lot of things nowadays.

It’s hard to describe how I’m connecting to some of the feelings expressed not only in this amazing review, but things I’m reading in the comments section as well (I’m not as eloquent as you, Dan lol). This comment struck me: “Personally, I’m trying to keep my religious traumas from boiling over into too many articles. I hated being a missionary. Church was a horrible experience for me from a very young age.” I also don’t want my traumas to boil over, but I have felt a similar way for most of my life. Not that the entirety of my church experience was negative, that would be unfair and untrue to say. But I can’t view my life story without the ever-present tinge of loneliness and alienation that resulted from feeling different than those around me, confined in a microcosm of society whose doctrine allowed no exploration of morality, sexuality, or anything really, outside of its prescribed norms. I’m straight, and yet for the majority of my youth, I felt like an outcast from normal society. I also grew up in a situation where “sexuality was something that could never be shared, only alluded to, elided, sidled around like a tiger seated in the living room.” (Btw, I’ve never seen that concept put into words to well). Because of my experiences, I will always sympathize with those that had to endure these experiences portrayed in this history-inspired game. I don’t know if this is irony or not, but I find that the Church and the Molly House are antithetical to each other, yet at the same time so damn similar. Both are places where people gather for a similar or shared purpose. Those who frequent these establishments are usually of a similar mind, and are sometimes considered by others as non-standard members of society. Both are supposed to be welcoming, but are wary of allowing people in that may disrupt their status quos. Despite some of these similarities, they are completely at odds with each other. I guess the true irony is that for the Church’s supposed claim for salvation for all (universalist soteriology as you put it), the Molly House would have been the more inclusive establishment between the two. Anyways, thanks for your insightful writing. It has more impact than you may think.

Thanks for sharing your perspective, fancy!

Just wanted to say that I really appreciated both the review, which is beautiful and moving, and this moving and well-considered response to the respectful question above. As a straight, male, former-evangelical atheist, it’s always good to be confronted with differing viewpoints and different ways of experiencing the world and how people reconcile personal morality with public beliefs in constructive ways. And I think so appropriate given the nature of this game, and the nature of the moment we’re living through.

I have Molly House coming soon in the mail, largely with the expectation of never getting it to the table with a group. Your review is a welcome window into the joy and caution of these 18th century men as revealed by the game–a tribute to them and a lesson for how we can make our way through times that seem benighted and dangerous.

Oh God, I’m crying over a board game review. Either I’m having a bad day or this was super good. Maybe both!

I very much hope it’s the latter, but please do take care of yourself if it’s the former!

i’m glad you edited this review so it no longer refers to the mollies as “men”

Happy to do it!

What an amazing review Dan, many thanks. I appreciate you including the personal details, lands much harder.

Thanks for reading, Greg!

One of your best pieces of writing (this is more than “just a review”). Chapeau!

Thank you!

A deeply moving and excellently written review, as always.

Your insights elevate our humble hobby. Bravo.

Thanks, Luke!

Cole Wehrle is doing some wonderful things with historical boardgaming: shining a light into the corners of (mainly English*) history and illuminating some unpleasant truths. That he does so via this medium is both different and cool.

Regrettably, there are still people in the world who live in places where the Society for the Reformation of Manners still exists, one way or another, and lead an existence that the Mollies in this game would recognise. I’ll certainly raise a gin in their honour when Molly House gets to the table.

Thank you for a considered and elegant review. I’m looking forward to the game more than ever. And to playing it with Chums.

* I’m English, but have a thick skin and don’t mind that our Imperialist past is getting the kicking it deserves via meeples!

Proof, if proof were needed, that you can review a boardgame with a high level of scrutiny and intelligence and yet never mention specific rules, playing pieces and base mechanics.

Bravura stuff and a massive testament to your skills as a writer (and willingness to lay your soul bare) as well as the desire by the designers to craft something meaningful.

Very impressed, keep up the good work Dan!

Thank you!

As ever with a game dealing with a serious setting (moreso one bearing Wherle’s touch), you’ve outdone yourself in the writing. I put this one aside for a moment where I would be able to fully dive in, and it did not disappoint.

Thank you so much for taking the time to play, to think and write about these games the way you do. It means a lot to me both as a gamer and as a person.

Thanks for the kind words!

It’s been mentioned already, but your deeply thoughtful, self-aware, and insightful reply in the comments to what some might take as a threatening question (not that it was posed that way here in any fashion) was heartwarming and illuminating. Wisely exercised vulnerability is incredibly powerful, and you’ve demonstrated that in abundance.

Cheers!

Thank you for the kind words, Brian!

Just got my shipping notification and came here to read this review out of excitement. What a beautiful and sobering piece to read this morning. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for reading, Olivia. I sincerely hope that Molly House proves as meaningful for you as it has for me.

Dan, I know I tell you this every so often, but my goodness, your criticism and board games writing are just art in and of themselves. I came here after listening to your conversation with Jo Kelly, and I am so eager to experience this game.

Thanks so much for the kind words, Spencer!

Pingback: A Visual Tour of ProtoCon | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Space-Cast! #45. Kelly House | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Kinfire Homeowners Association | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Lovers’ Quarrels | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2025! The D.T.R.! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Board Games | SPACE-BIFF!