Meet the Faceless Cusk

We all know that one of the juvenile pleasures of Wingspan is calling out the birds that sound like human anatomical features. Abbott’s Boobie! American Woodcock! Truly, I will never age past thirteen.

Finspan is the second spinoff of Elizabeth Hargrave’s unexpected smash hit, following last year’s Wyrmspan by Connie Vogelmann. Designed by David Gordon and Michael O’Connell, Finspan drops us into the sea. It also changes the nature of the game. Now, instead of calling out funny body parts, it’s all about announcing which fish resemble the people at the table. Me? I’m a Porkfish.

Oh, there are more substantive changes, which I’m sure you’re hoping to read about. We’ll get there. But this transposition of setting from the skies to the sea accomplishes a major tonal shift. Birds are beautiful. Fish? Sure, some fish are beautiful. Some. But all fish are weird.

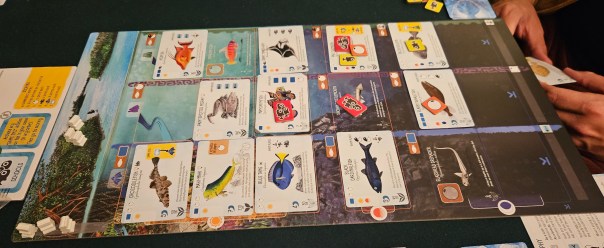

That weirdness has implications for Finspan. This aquatic setting is, if you’ll excuse the pun, more fluid than its predecessors. Where Wingspan and Wyrmspan asked players to arrange their creatures across a three-tiered tableau, the ocean is more changeable. Once again there are three portions to each tableau, but each one reaches deeper, hosting six cards across three layers. Surface fish stick to the sunlight zone, but as the light is dimmed by all those gallons of salt water the true oddballs come out to play. By the time one reaches the vents at the ocean floor, every fish is a monstrosity.

Moreover, fish aren’t content staying put. Larger fish regularly gobble up smaller prey, replacing them in the tableau. This impermanence makes placements more flexible than ever. If you’re in doubt about placing a fish, don’t worry, something better might come along later. There’s no corrective to a poor placement quite like turning the offending card into a snack.

As in previous titles, fish lay eggs. But this time around, those eggs hatch into young. Certain triggers permit these smaller fish to dart across the tableau, avoiding spawning locations or grouping into schools for serious dollops of victory points. Thanks to this emphasis on replacement and motion, Finspan’s tableaus are living things. Wingspan and Wyrmspan feel trapped in amber by comparison. It doesn’t quite offer the player-created ecosystems of Oceans, but it is a few steps closer, coming across as an exhibition of something organic rather than a collection under glass.

With so many changes, Finspan risks appearing like another step upward on the mountain of complexity. In fact, this is a simpler title than Wyrmpsan. If anything, it shifts the complexity the opposite direction, producing a ‘span game that even Mandy Patinkin could figure out.

For example, there are only two actions in the entire game. Either your turn is spent placing a fish or exploring a section of your tableau. Like everything else in Finspan, the first option is surprisingly easy thanks to the absence of traditional resources. Rather than gathering and consuming the berries and gold that were hallmarks of previous ‘spans, fish generally require other sacrifices. Eggs, perhaps, but more often the cards in your hand will do. These spent cards are sent to your own private discard pile, where they wait to be rediscovered at some later date. Again, the emphasis on mutability ablates the usual apprehensions that come with throwing something away. Just because nobody has seen evidence of a coelacanth since the Late Cretaceous doesn’t mean you won’t find one puttering around off the coast of South Africa in 1938. Indeed, it’s fairly common for the game to pause while somebody peruses their stack of discarded fish for the right specimen to resurrect.

Similarly, diving is as easy as running down your chosen column and activating any gold-framed abilities. As with Wyrmspan’s stable of dragons, there’s a sense of adventure to the process, your diver plumbing the depths and witnessing each fish’s ability. This is when most of the game’s effects trigger: fish spawn eggs and are rediscovered, young come together in schools and dart to safety, new fish migrate into your hand. It feels good, every detail honed to its most concise expression.

Other details keep the playtime trim and the complexity manageable. There is no upkeep in between rounds. The objectives for bonus points are clear. Even the pool of available actions has been shored up; they neither diminish, as in Wingspan, nor can they be purchased, like in Wyrmspan. The whole thing feels like it’s been through a hundred iterations to produce maximum glide.

Of course, that same smoothness comes at a cost. The number one question rattling around everyone’s heads is whether we really need another ‘span game. Does Finspan alter the formula enough to be a worthy contender for those who have already enjoyed — or, depending on their disposition, endured — two of these things?

It depends. To be absolutely clear, Finspan comes across as a beginner’s ‘span. It isn’t simplistic or anything like that, no My Little Wingspan, but certain absences reduce its friction to such a degree that it sometimes feels slippery. Like its predecessors, this is a game that features plenty of churning for cards that will work well together. Given the relative simplicity of those cards, however, workable combinations are more apparent than before. You’re building an engine, but it’s a straightforward engine, with the gears marked in advance. You’re assembling a system of pulleys, not an outboard motor.

There’s also the question of taste. My eleven-year-old lists Wyrmspan as one of her favorite games of all time, to such a decree that she has stolen its dragon guidebook more than once. Finspan she likes well enough, but prefers the more fantastical elements, not to mention some of the woollier edges, of its draconic kin. And I mean “draconic” in both senses of the word. Cate loves dragons, but she’s also developing a taste for challenge, and the tougher restrictions of Wyrmspan are more to her liking than the low-consequence placements of Finspan.

My own feelings differ somewhat. As popular as they were, Wingspan and Wyrmspan had a few problems. Chief among them was a playtime that could easily balloon to two hours or more. This smoother expression of Hargrave’s tableau system keeps the pufferfish from showing too many spines. There are still moments of slowdown, especially when somebody draws a bunch of new cards or needs to pore through their discard pile, but these interruptions are shorter-lived than in earlier ‘spans.

Similarly, as a lower-stakes option, I find that Finspan is a better fit for my multiplayer-solitaire appetite. There are only a few moments of intersection between players, such as when a fish populates everybody’s leftmost column with eggs or allows everybody to move a school to a better location. But these abilities only rarely hinge on other players’ activities. There are no shared pools to draw from, whether card markets or a resource pools, and there’s nothing like Wyrmspan’s guilds. While this reduces the number of active decisions between players, it also keeps the overhead tight. There’s no such occurrence, for example, as when somebody nabs the card you wanted right before your turn.

This might sound like I’m damning the game with faint praise. “Hey, at least it’s shorter!” That isn’t my intention in the slightest. Rather, Finspan works because it’s a faster, more fluid, and less penalizing approach to Hargrave’s system. Its emphasis on letting you rejigger your tableau feels good on the fingertips, letting you adapt to new cards on the fly rather than feeling locked in to a particular approach. And this isn’t handled flippantly. Newer cards must be larger than the one being covered — this is where the whole “finspan” moniker comes into play — producing decisions that are tougher and more permanent than tossing the odd fish into your discard pile.

All told, Finspan takes the ‘span games in an intriguing new direction, one that’s clearer and easier to onboard, but still delights in the wild world of nature and demands a certain degree of skill to play well. And its subject matter, the slimy freaks that populate our oceans, set themselves apart from the game’s soaring counterparts with their increased mobility, appetites, and weirdness. Even as I grow warier of this genre as a whole, it’s nice to see that the system still has legs. Fins. Whatever.

Speaking of which, Geoff is a faceless cusk. Look it up.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read a 3,000-word overview of the forty-ish movies I saw in theaters in 2024.)

A complimentary copy of Finspan was provided by the publisher.

Posted on January 17, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Finspan, Stonemaier Games. Bookmark the permalink. 5 Comments.

Awesome, thank you Dan. I’m so tired of people bashing subsequent ‘Span games as knock-offs, cash-grabs, or whatever other hyphenate their overly judgy minds concoct. I personally really like Wyrmspan, and can’t wait to try this too!

I agree. When it comes to Stonemaier, people have weird expectations. Wingspan is popular for good reason, Wyrmspan rocks, and this is a smooth point of entry that will appeal to a bunch of people. There’s no conspiracy.

Excellent review. My copy is in the mail and I can’t wait to get it to the table. My wife loves Wingspan but the added complexity of Wyrmspan didn’t do much for us, and we bounced pretty hard off the theme. A more streamlined version that’s maybe easier to get to the table, and without fantasy elements, sounds like just the thing!

I wonder: have you played Reforest? It’s a small card game that was kickstarted this past year. It has some (mostly superficial) similarities to Wingspan, but it actually sounds much closer to Finspan in terms of gameplay. Reforest also uses a system where you pay for playing cards by discarding cards from your hand. It’s a brilliant solo game, in my opinion.

Sorry, but I haven’t even heard of Reforest, let alone played it!

Pingback: How to Train Your Fledgling | SPACE-BIFF!