All Welrod and Good

Every so often I have the opportunity to play what I call an enhanced choose-your-own-adventure game. Not unlike Edward Packer’s beloved children’s series, these are games about making narrative decisions and seeing how they play out, usually with a lot of “turn to page 101” and “turn to entry 344.” The “enhanced” part comes in when these choose-your-own-adventures include tabletop elements from outside the book itself, such as dice rolling, action points, or a story sheet to keep track of narrative consequences — the most recognizable example being, naturally, Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone’s Fighting Fantasy series.

Right up front, here’s my declaration: Dave Neale and David Thompson’s War Story: Occupied France is easily the best of these titles I’ve played. Full stop.

Set during the dismal days of World War II, War Story: Occupied France casts players as operatives of the British Special Operations Executive. Refugees from Occupied France, you have been trained in espionage, spycraft, and combat, and are now deployed to assist the French Resistance in throwing off the Nazi yoke. Over the course of three acts, each of which takes maybe ninety minutes to complete, you will enter enemy territory, make contact with Maquis rebels, and conduct various operations meant to hinder your foes.

Right away, Neale and Thompson are careful to establish the proper tone. The landscape is cold and damp, your contacts skittish, and enemies pose a genuine threat even on those rare occasions when you outnumber them or can take them by surprise. No decision is free of paranoia and self-doubt. Your agents are likely doomed, if not to death or capture, then to injury and defeat. Total success is a pipe dream, at least on the first pass through the story. This is still a fantasy, but it’s one that pays uncommon attention to the realities of 20th-century espionage. I was darkly delighted, for instance, when my characters were presented with an informant who threatened to reveal us to the Nazis unless we paid him money we didn’t have, and we were given the option to either talk him down, kill him outright, or tail him to his bunkhouse. It’s frustrating when a narrative doesn’t provide branches that it characters would naturally consider, but here we were presented with precisely the alternatives that would tickle a spy’s instincts. Now that’s verisimilitude!

Because this is a choose-your-own-adventure gamebook — technically three gamebooks in a single box — most of your time is spent hovering over text entries. Not only are these paragraphs finely written, they also leverage the format’s natural strengths. One friend mentioned that it might be nice if the game were an app, better to minimize the time spent flipping between pages. Except that so happens to be one of the best things about choose-your-own-adventure books. The downtime between entries offers a natural pause, building suspense as you wait to see what happens next.

And if I hadn’t already made it abundantly clear, suspense is exactly the right mode for this story to operate in. Multiple times per act, my group would stop to fret over a decision. Sometimes, more often than we expected, we were genuinely assessing which course of action would be safest. Other times, a certain gaminess presented itself. It’s wholly natural, as people who have thumbed through dozens of these books in the past, to consider the authors’ priorities and intended twists. To the credit of these authors, their presence is rarely overt. Even in those instances when they step into the foreground, usually to ensure an encounter doesn’t veer too wildly from their intended course, they deploy a mild touch.

Anyway, I might be seeing faces in the foliage. That Neale and Thompson occasionally creep into our decision-making feels appropriate. Every now and then I use my thumb to mark a previous entry, just in case we require a quick rewind to undo some narrative bullshit. In those moments, I think of the resistance fighter muttering a prayer under their breath before they breach into an occupied police station to free a comrade from interrogation. The ability to see the narrative’s tethers, even to reverse them and explore alternatives, is a feature of the form, not a cheat.

The greatest strength of War Story: Occupied France, however, is that this is not only a storybook. These are designers in addition to authors, and their pedigree in tabletop allows them to elevate the experience in every way.

Some of these additions aren’t strictly necessary; they serve to enhance our appreciation rather than to shoehorn in gameplay. Each scenario presents a map, not because we need to track our position — geographical distances never matter — but rather because seeing our fictive location adds to the game’s sense of place. Even then, there are some subtle overlaps. At least once, we were asked to examine the map for clues about which way somebody might have traveled. The same goes for conversations within the storybook; offhand comments might be present merely to add flavor, but in other instances offer clues about a character’s position later in the narrative. These blurred lines increase the game’s tensions, keeping players on edge even when they’ve adopted a more passive role as a listener.

And then there are the moments when passive play is shattered. At various points, another map is laid on the table, this time displaying lines of fire, lookout positions, hiding spots. In these cases, players are required to position their agents for maximum impact. A German patrol is ambling our way — should we hide in the brush to jump them along the path or conceal our weapons expert on the nearby ridge with our sole rifle? We’re breaching a radio station — should we lay down suppressing fire on the front entrance or sneak our agents in through the back door? We intend to ambush a convoy — do we put somebody on lookout or keep all our guns in the fight? Some answers are better than others, and it pays to know your agents’ capabilities, but none of these encounters come across as perfunctory. Something is always liable to go wrong.

It almost goes without saying that characters have various stats. Indeed, it’s a good idea to choose a team with complementing abilities. Some characters excel at talking their way out of trouble, others would rather shoot trouble in the forehead. Neglecting any one arena is often surprisingly perilous. On one mission, we didn’t bring anybody with technical know-how, an omission we sorely regretted once we realized nobody on the team knew how to assemble a machinegun.

That said, the game does offer a pool of skill tokens that can be spent to overcome shortcomings. These pools, naturally, are severely limited, turning players into misers as they assess whether this is the right time to expend one of their rare weapons tokens. This is War Story: Occupied France at its most overtly gamey, but it functions as a stand-in for any number of concepts that would have been too burdensome to include on their own: stamina, ammunition, fog of war, maybe even luck. If anything, the tokens can be misleading; the punchboards include a score of the things, but you’re lucky to haul a half-dozen into any given mission. It’s as though Neale and Thompson are waging psychological warfare on their players, promising sufficient aid to accomplish your objectives with ease, only to withhold all but the barest assistance.

Are there hiccups? You betcha. There’s already an errata sheet, an essential series of fixes for any game that demands precision. Only once during our campaign, I was sent to the wrong storybook entry. But that flub was notable, resulting in significant confusion as we sought to course-correct, not to mention narrative intrusion. We were able to get back on track, but it always rankles when early players become unwitting guinea pigs.

Apart from those misprints, though, I haven’t really suffered any downsides. Even the game’s book-work is handled smartly. It’s possible to play one scenario at a time, but the narrative shines when experienced as a linked three-act campaign. Many enhanced choose-your-own-adventure games suffer here, demanding time-consuming and persnickety bookkeeping, usually with multiple character sheets, boxes or baggies for storied keywords, and so forth.

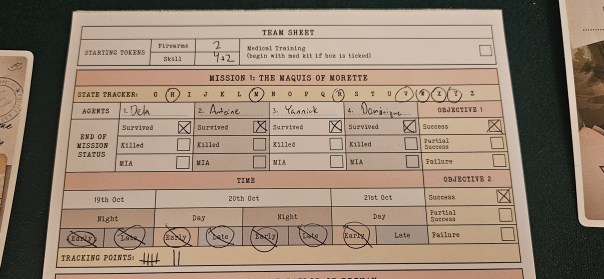

By contrast, everything here is confined to a single sheet. Each individual scenario receives its own section, where your agents (and their fates) are recorded, alongside trackers for your objectives, the passage of in-game time, and how much attention your infiltration is kicking up from the Nazis. Most of these details have implications only within individual acts of the campaign; for example, you don’t need to worry about whether you finished last month’s mission at noon or sundown.

The consequences for your actions, however, might prove far-reaching. Here Neale and Thompson opt to keep the details under wraps. Certain decisions require you to mark a letter — “circle the letter S in your state tracker,” for instance. Later entries will then invoke those marks to trigger unexpected outcomes. Rather than drawing a card that says “You raided a police station in the middle of the day, you big blundering doofus,” you circle the letter P and hope it doesn’t come back to bite you too badly.

Of course, I’m not saying that “memory cards” are a bad thing. Indeed, when Ryan Laukat deployed them in Sleeping Gods, I considered them a smart way to keep tabs on that game’s branching narratives. Here, though, in a story that repeatedly highlights the terror of uncertainty, there’s no more appropriate way to keep players second-guessing their every activity. In some cases, there’s even a tenuousness between a letter’s cause and its effect. Such moments are especially thrilling from a narrative standpoint. When a trigger is squeezed, players are often left to speculate at the reasons their current misfortune is befalling them now. Within the game’s fiction, the message is clear: this is war’s dirty work, sometimes bad things happen for unknown reasons, get used to it. When it comes to inculcating both the stoicism and anxiety of a war-weary soldier, Neale and Thompson exhibit masterful work.

That, ultimately, is perhaps the premier, or at least most holistic, of War Story: Occupied France’s accomplishments. This game is so good, with such a robust sense of place and tone, that even its little accidents, like those surplus tokens, come across as intentional and considered. (NOT, I want to stress, its misprints! Those suck!)

In short, this is the finest enhanced choose-your-own-adventure game I’ve played. It’s as dense as a brick and strikes the cranium with every bit as much force. And although its treatment of its subject matter sometimes risks becoming overly tidy, it defies expectations with moments of grit and fear that are uncommon to the genre. This is the good stuff. I very much hope that Neale and Thompson have another volume chambered.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on December 5, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Osprey Games, War Story: Occupied France. Bookmark the permalink. 16 Comments.

thanks Dan, is it ok to link to a blog post or two on the subject of narrative in games?

Go for it.

STORY GAMES BLOG PART 2

https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/story-games

STORY GAMES BLOG PART 2

https://armpitgames.wordpress.com/

I think sometime after writing these blogs, Greg rewrote his original article linked in PART 1 and scrapped his subsequent article I link in part II which is now a dead link

There are countless things I disagree with Costikyan about. His essentialism around what constitutes a good game is one of them.

quickly googles ‘essentialism’

I just picked this one up to play with my brothers. Glad to read your endorsement.

What about replayability? Is this a one-off legacy type of thing, or can you shelf it for a while, come back to it, and experience the excitement all over again?

You can absolutely shelve it and play again later. There’s some variability in how scenarios play out as well.

Dude, don’t discredit how scary Dutch cows can be…*shudder*

MEW.

Wholeheartedly agree Dan! The Neale/Thompson combo lived up to my expectations and then some! I like it better than Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective as we’re given the choices to explore rather than guessing which creates the nervous deliberations you described. We loved the palpable tension just before the reader started our chosen next paragraph with a glum look! Apart from checking the errata when reading an entry, this is one of my favourite games of the year and one I’m looking forward to coming back to explore the other story avenues soon!

I played a ton of Fighting Fantasy books (as well as other series) as a kid and while a few of them did require some thinking (Steve Jackson’s Creature of Havoc or Sorcery series come to mind), most of them only offered mindless, random choices (as in “Are you going to turn left or right?”).

I’m always a bit wary of narrative games for that reason, as that was also my experience with Dungeon Degenerates (great illustrations, no real decisions). I enjoyed Sherlock Holmes Consulding Detective’s Irregular set a great deal, but I’m wondering how this one fares in that regard.

I don’t think the decisions are uninformed in this one. There’s no “right or left” crap. Pretty much every decision, the ones I saw anyway, made narrative sense.

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Better Together! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Resistance in France | SPACE-BIFF!