Cute as a Button

Posted by Dan Thurot

In video games there’s the concept of the “demake,” in which a particular title is reimagined according to the limitations of earlier hardware. If there’s an equivalent in analog games, it might be the impulse to miniaturize. If so, there may not have ever been as extreme an example as Gloomhaven: Buttons & Bugs.

The original Gloomhaven, designed by Isaac Childres, is famously enormous. I would list a sampling of the contents (seventeen heroes, ninety-plus scenarios, etc.), but even that’s an exhausting endeavor. By contrast, Buttons & Bugs fits in the palm of one’s hand. Not comfortably, mind you. It’s a rather big miniature box. You could probably deal some damage to an intruder if you pitched it with enough force. But compared to Gloomhaven, the shrink ray has done its job.

Here’s the thing. Just as a demake can prove clarifying of the core elements of a video game, so too does this miniaturization. By stripping out the many many many things contained in that big box, it zeroes in on what makes Gloomhaven so interesting — and to some degree, so limiting.

To play Buttons & Bugs is to pass through a series of successive surprises. There’s the first one, where upon opening the box and rifling through its contents, it becomes apparent just how tiny this thing is. The miniatures are indeed miniature. The enemies are easily-lost plastic cubes rather than cardboard standees. Maps, which in the original required painstaking assembly from separate heaps of rooms and corridors and obstacles and traps, are now printed on a single card. The scenario instructions and story are printed on the reverse side.

But this surprise gives way to another: namely, that Buttons & Bugs is shockingly close to its source material. When it was announced that Buttons & Bugs would be a miniaturized and solitaire-only version of Gloomhaven, my mental image was a few steps removed from the original. Of course it would draw inspiration from Gloomhaven. But surely there would be major departures.

Depending on how one identifies Gloomhaven, that departure is variously gauged. Buttons & Bugs has its roots in a microgame, an eighteen-card title called Gloomholdin’ by Joe Klipfel. Now Klipfel and Nikki Valens have teamed up to create this more full-blooded project. But while the eighteen card limitation has been jettisoned, in terms of volume there are significant departures. The whole experience unfolds across a twenty-scenario campaign, for one thing — and you won’t see all of them in a single run. There are only six character classes, and leveling up is more linear than in the base game, with particular abilities swapped out for direct upgrades. There’s no overland map, no intermission events, no cash to earn or shops to spend it in, no stickers for modifying cards. If “volume” is how one identifies Gloomhaven, then this could be considered a massive departure. And volume shouldn’t be discounted. Even Jaws of the Lion, the “lite” version of Gloomhaven, is unusually generous. These games are appealing not only for their systems, but also for how they feel like worlds unto themselves, bottomless wells of possibility that demand to be explored.

So when I note that Buttons & Bugs hews closer to its source material than expected, I’m speaking largely in mechanical terms. And it’s true: nearly every system that makes Gloomhaven Gloomhaven has been faithfully reproduced.

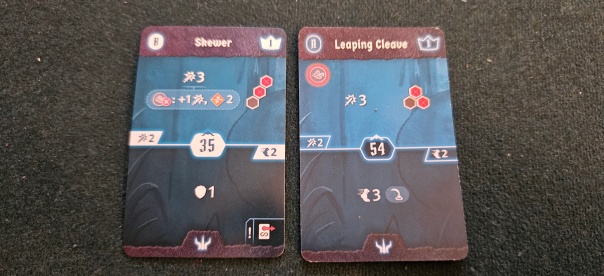

The biggest example is the card system that governs how your character operates. As in the original, every turn revolves around the selection of two cards. From a hand of various moves, you pick the top half of one card and the bottom of another. In general terms, these produce an attack and a move, letting your character reposition on the map and bop enemies on the nose. With a club. As the game progresses and your abilities develop, you also gain a sense for how to manipulate these abilities. Sometimes you’ll select a card that keeps your feet planted but blocks enemy strikes, or maybe you develop an ongoing ability that makes your attacks more potent. Either way, you’ll always be picking two cards and enacting those tops and bottoms.

Buttons & Bugs replicates not only this basal concept, but also the way it operates within any given scenario. If you know Gloomhaven, you know that it’s something of a race against time — or, more accurately, against your body’s collapsing stamina. As cards are used, they become unavailable, first disappearing to a temporary stack and then, when that stack is refreshed back into your hand, withering piecemeal into a more permanent discard. You can lose a fight in the usual way, beaten to a pulp on the floor, but also by getting too winded to continue the battle.

In this iteration of the system… well, pretty much the same thing happens. There is a slight difference. Cards begin with one pair of abilities, but then flip to their reverse side and a second set of options. Only then do they collapse into your pile of tuckered-out moves. Despite that minor divergence, their function remains more or less the same. Every battle is a contest to meter out your abilities before your muscles seize up. It’s a puzzle game of sorts, a brawl in which you can kick someone into the fireplace and swing your weapon in an arc and maybe toss a bolt of magic, but only each option can only occur once before you require a breather.

Along the way there are other departures, although once again they’re smaller than one might expect. Gloomhaven was notable for using One Bazillion Decks to govern everything from enemy behavior to whether a hit earned plus-one damage or whiffed entirely. Those decks have been pruned down to a few cards and a die. Enemies each come with a card showing three moves. When the round begins, you roll to determine which of those moves they will take, including their initiative number. When an attack connects, you roll against a table to see whether your attack is shifted up, down, or stays neutral.

But even this departure is surprisingly close to the feel of Gloomhaven, if not its actual systems. Somewhat famously, Gloomhaven didn’t use dice. Instead, your hits were modified by a deck. As the game progressed, you were allowed to alter the composition of that deck, swapping out flubs for better cards and thereby improving your chances that any given pull would be worthwhile.

The deck might be gone, but the improving set of modifiers is still there. Here you roll a die, but only as a shift on that modifier table. Before you attack, you can see the possible results that might modify its outcome. Maybe it could be doubled this round. Maybe next round it could miss entirely. Maybe, if you’re playing as someone who takes advantage of the game’s magical elements, you will generate some fire or wind to boost a spell. Over time, your character earns new and improved modifier tables, letting them pull off cooler moves. It’s weirdly close to the modifier decks that governed Gloomhaven, generating similar considerations of timing and probability.

These various proximities have another consequence. Much the way a demake strips out the emphasis on hardware to highlight the essential core of a video game, this miniaturization snaps Gloomhaven into focus.

For one thing, even after copious subtraction this is still very much a game that thrives on volume. Despite having been shrunk in the wash, there’s still quite a bit of wiggle room in these trousers’ waistline. Each character is a fully realized set of abilities, modifiers, and gameplay considerations. There are items to equip, this time printed on the margins of the scenarios you’ve beaten, to shore up weaknesses or grant a slight edge over your foes.

Those slight edges are often crucial. I mentioned that Gloomhaven sometimes feels like a puzzle game. That’s true, especially in the later scenarios, where the difference between victory and repeating the scenario often walks a razor edge. If you bring the proper abilities and items, head right instead of left, make sure to leap over a particular obstacle at the right moment, you’ll prevail. Except there’s one additional element. Chance! Of course it’s chance. Because in addition to all your preparations, proper ability selections, and moving to the right spots, you’re also hoping to roll the proper modifiers in order to take down those enemy centipedes and mice in two hits apiece rather than three. It’s not unlike solving, say, a chess puzzle, except captures also require you to succeed at a roll. Otherwise you’re thrown back to the preparation stages and tasked with doing the whole thing over again.

This has a mixed effect, both the source of its depth and a font of no small amount of frustration. The result is a system that stands astride two contrasting genres, and often does so without losing its footing. But not always. Which, by the way, is why I’ve always enjoyed and appreciated Gloomhaven but never made it more than, oh, twenty-ish battles before petering out. Which is hardly optimal, as some of the series’ most interesting ideas, like modifying cards with stickers, retiring heroes, and swapping them out for more challenging unlocked classes, tend to only reveal themselves gradually. It’s a relief to feel like I’m not missing out on anything, as this smaller format makes it possible to complete the full campaign without investing hundreds of hours into a system that can be as infuriating as it is entrancing.

At the same time, Buttons & Bugs suffers from a particular subtraction that makes it all the harder to hold my attention: it’s solitaire-only, and I don’t mean only in terms of player count. Your adventure is limited to a single hero. If you follow the advice of the starter booklet and select the boring Bruiser, you will continue on as the boring Bruiser until you wrap up the campaign or choose to restart. If you realize after ten scenarios that the Mindthief is a little too technical for you, well, that’s too bad.

In a party, this isn’t a problem. Part of the appeal of the original Gloomhaven was found in the way a group of characters riffed on one another. That’s one of the significant strengths of engaging in a longer campaign. Because heroes often retired partway through, it wasn’t uncommon for mismatched adventurers to find themselves forced to cooperate. At any given moment, you might have a veteran Spellweaver and a struggling Tinkerer in fellowship with a Soothsinger freshly graduated with a dual major in soothing and singing. The way scenarios scaled their difficulty to match your party level wasn’t without its bumps, but it did permit players to perform as part of a team, to pave over their weak points, or to experiment with multiple classes. Even boring characters became exciting as they learned their place in a mixed mercenary company.

In Buttons & Bugs, it wasn’t long before I found myself missing that company. It wasn’t only that I was tired of playing as one particular class. It’s that I wanted to make decisions based on wider considerations than a single character affords. I wanted to let one character take a breather while someone else tanked hits, or have a pal prep an element so I could trigger a powerful spell, or engage in some physical comedy by shoving an enemy back and forth over a thicket of spikes. None of these things are possible. Instead, some decisions are even straitjacketed, such as the need to pair certain cards in order to trigger elements and the spells that will benefit from them.

And it’s fine. Really. The tradeoff is a shorter campaign, with a tighter narrative and guided leveling and a relatively compact selection of items. I realize that in wanting both a compact experience and a party-based campaign, I’m trying to snarf my cake while eating it. But that’s precisely what I want. To eat my cake. And to snarf it. To have these compact campaigns alongside the progression and abilities of at least two heroes. Maybe, even, to also miniaturize the retirement concept and swap out a hero midstream.

As an experience, Buttons & Bugs is clarifying. There are missteps here. The components have been reduced in size to such a degree that they’re fiddly, and offloading the actual rulebook to a web document strikes me as a grave misstep. At the same time, Buttons & Bugs demonstrates many of my favorite things about Childres’s masterpiece. As a tightrope walk between a puzzle, a race, and a random outcome generator, Gloomhaven has yet to be paralleled.

At the same time, Buttons & Bugs also highlights that some of the best things about this series can’t be reduced this sharply. Despite the overwhelming nature of Gloomhaven’s bigger sets, it’s precisely the breadth of possibility that I hunger for. This isn’t inherently missing from a smaller format, either; one can imagine a campaign of twenty-something scenarios that still lets two or three characters work in tandem. If it had permitted even one additional hero, just enough to allow for some interpersonal dynamics, I would have been thrilled.

Put everything together and you get a flawed but expressive — and surprisingly faithful — miniaturization of Gloomhaven. I’ve enjoyed my time with it. Had some of its subtractions been reversed, it could have been rapturous. What I missed most wasn’t a system or a sprawling campaign, but the presence of a second party member.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

Posted on May 29, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Alone Time, Board Games, Cephalofair Games, Gloomhaven, Gloomhaven: Buttons & Bugs. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

Can you imagine if they had given you two characters, you mashed the two decks together, and each turn you still only played two cards where the top has to be for one character and the bottom for the other character, giving you an action flow much more like Guards of Atlantis?

Yeah, that’s me up there trying to will this into the universe.

Would play.

I realize this would totally destroy the balance, but could you just play with two of the provided characters? You’d have to manually record some stuff and choose which character got the end of scenario reward, so it’s definitely not ideal…but it might be possible.

It might. Somebody could probably figure out how to make it work. That’s beyond my remit in reviewing the game, though.

Agreed. Part of Gloomhaven’s core is the dynamic between party members. But some of these solutions are ingenious.

You can play this game two-player with minimal changes:

The enemy changes basically simulate making the enemies the ‘Elite’ version like when playing regular Gloomhaven, minus the increases to movement and range that some of those enemies get because the combat arena is so small.