Our House Is a Very Very Very Molly House

I often joke that I’m a class-four prude. Like many jokes, this one hides a kernel of truthfulness. For reasons that are far beyond the purposes of today’s discussion, sexuality is not something I discuss easily or often. When I do, it’s often behind a veil of playfulness. In laughter and mirth, the untouchable is momentarily set free.

Although the comparison is an imperfect one, that also seems true of molly houses, gathering places such as coffee houses or taverns where homosexual men in 18th-century England could socialize freely, veiled from the gaze of polite society. In some ways, their idea of queerness was different from ours. Indeed, they lacked terms like “queerness” at all. The laws of the time lumped homosexuality and bestiality together, and those who were arrested could be pilloried or even hanged.

Despite these penalties, men risked shame and death to create places where they could become more fully themselves. That’s the topic of Molly House by Jo Kelly and Cole Wehrle. Molly House was one of the finalists of the first Zenobia Award. Now it’s nearly here, and I can safely say there’s nothing quite like it.

If Molly House has a single watchword, it would probably be “consent.” In the positive sense, that players adopt the role of homosexual men looking for companionship in a time and place hostile to their existence, and must therefore navigate the gardens and arcades of London carefully and considerately. But also in the negative sense. Because you are a gay man in the 18th century, there is a very real possibility that your agency will someday be stripped away. And, at a more meta level, that question of consent transcends the table and poses itself to the players themselves. What is consent? What does it mean when it’s offered from one person to another? What does it mean when it’s stolen? One doesn’t need to have lived under the radar to grasp the implications of these questions. Anyone who’s tried to make new friends as an adult will know the anxiety well enough.

To allow the game to center that anxiety, it befits Molly House that the turns are straightforward. In nearly every case, you travel to a new space and take an action. There are limitations. You can only travel so far, a terrible imposition when you need to reach the other side of the map but don’t have adequate range to do so. Further, the black pawn denoting the presence of the Society for the Reformation of Manners, self-appointed constables bent on suppressing everything from brothels to profanity, are best avoided.

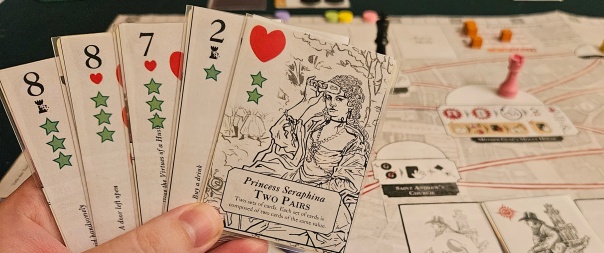

And then there are the actions themselves. Every single action will call upon you to draw from the deck. For the most part, the deck proffers a jumble of opportunities, full of cards across four suits that represent your budding friendships, items that might be appreciated in the festivities at the nearby molly house, perhaps even a molly for hosting such a good time. But there are perils as well. These appear in the form of constables, eight of the spit-shined bastards, two per suit, ready to spoil your draw.

Expect those draws to be spoiled. Often. There is no such thing as a safe moment. One minute you’re confessing in church, or perusing the Covent Garden Market, or announcing yourself at the Axe Hotel and Coffeehouse. No matter what you do, there’s an element of exposure. Literally: You place certain cards face-up in front of you, showing them to the table. This is the peril of trying to find people like yourself. You must reveal a portion of who you are. It’s an apprehension we all know too well, risked every time we step out of our comfort zone to announce ourselves to the wider world.

Here, though, those apprehensions may have acute consequences. The next minute, when you draw, it’s entirely possible a constable will appear. This halts the draw immediately, no matter how many cards would otherwise be peeled off the deck. And then the constable pores over the things you’ve exposed. Depending on whether this is the first or second constable of their suit — and depending on the version, because Molly House is very much still in development and every one of my four plays has been slightly different from the others — the constable subjects everyone else at the table to scrutiny as well. Then your agency is stripped. Cards are lost. Maybe you’re deemed for the pillory. Chits are drawn from a bag and concealed in front of you. These speak of shames that may one day be made public. In game terms, negative victory points. Even, if you’re bold or terrified or both, another way to win.

It’s important to first establish the penalty for your search. There is no moment in Molly House when you don’t feel hunted. Whether you’re cruising the arcade in search of a lover or revealing your identity to the local priest under seal of confession, it’s never possible to shrug off the fear entirely. There’s a constant note that runs throughout the game, like the sound of a horn just below the pitch of hearing that nevertheless lays a cold hand on your breastbone. At all times, you risk discovery and punishment.

This draws the game’s objective into stark contrast. Your goal may be abstract, but it’s also more… not tangible, but whole than anything as airy as a “victory point.” Here the points are called “joy,” and they are an objective as solemn as any other. In respectable society, every season the ton convenes in London to find suitable matches for their scions. Their goal, stated frankly, is to arrange the proper mates for themselves and their offspring. Without joy, what a sterile and sorrowful pursuit this might be. Most who sought refuge in molly houses were workingmen, but perhaps your character is one of the few who once took part in that annual ritual. Either way, here they are, searching for joy and companionship despite the dangers such a search presents.

In this search, all roads lead to Mother Clap’s Molly House, the centermost location on the map and the appointed destination for the cards you’ve gathered. Here players may take part in festivities, the game’s most involved but also most rewarding action. These are multi-step affairs. The host must bring a molly, who sets the terms for the engagement. Historically, activities in molly houses were wide-ranging. There was sex, of course, but also feminine-coded rituals such as cross-dressing, cuddling, speaking to one another in women’s voices and with women’s vocabularies, and the conducting of marriages and mock births. I don’t list these rituals in the spirit of gawking; as I noted earlier, 18th-century ideas of queerness were different from ours, and these were but one manifestation of queer identities. Beyond the abstracted suits of the cards, Kelly and Wehrle don’t go into specifics. It’s enough to know that a festivity is when everyone at the table comes together in their shared pursuit of joy. Pun intended? I’ll never tell.

In game terms, the aforementioned molly sets the objective for the festivity via a hand of cards. Aunt England declares a four-card flush; Orange Deb insists on a six-card run; Queen Irons prepares for a full house. Because of the scattershot way that cards are gained — and the very real possibility that they will be confiscated — it’s nearly impossible to fulfill these objectives alone. So everyone pitches in. Everybody has the opportunity to present an item that alters the rules: a dress that makes certain cards more valuable, a fiddle that attunes a shared suit anybody can chase for extra points, gin that provides a wild and joyous night but also risks attracting the local constabulary. Then everyone goes around the table and adds cards, one at a time. If the right cards are played, joy is scored and the contributing cards become part of their character’s reputation, potentially scoring further points later. Otherwise the festivity fails and everybody picks up their cards for a later attempt. Either way, everybody holds their breath while a few cards are drawn to see if the Society for the Reformation of Manners crashes the party.

It’s a little bit wondrous, these festivities. Despite being a contest at heart, the camaraderie is genuine. Everybody may contribute, everybody may benefit. Together, perhaps something worthwhile and vibrant emerges. In one sense, Molly House is not all that far off from the many games about rebels and insurgents who meet under cover of darkness, each bringing their own scrounged equipment and intelligence together in an effort to throw off their shackles. Except in this case, the objective isn’t revolution. It’s living well and honestly.

Like most other rebellions, this is a war its participants would rather not wage at all. Life is hard enough and dangerous enough — love, too — that there’s no need for prowling vigilantes and hanging laws to make the pursuit of joy worthwhile. Nobody wants to be betrayed by their closest confederates.

Because that’s a very real possibility in Molly House. Whenever you’re caught by a constable, you’re forced to draw one or more chips. These mostly slap you with negative points, representing the impugning of your reputation and perhaps dangers to your livelihood and wellbeing. Mixed in with the other chips are informer tokens. In fitting with the game’s engagement with consent, it’s always optional to take these. In fact, drawing informer tokens can be beneficial. You show the table what you’ve drawn and chuck them back into the bag. Somehow you’ve escaped this brush with the law unscathed.

But as the game progresses, the pressures of living on the fringe of society may become too much. You’ve become a target for harassment by the constables. Mother Clap’s is ever closer to being raided and shut down. Maybe even petty jealousy plays its part as rival participants eclipse your own pursuit of happiness. Regardless of the reason, there are sufficient advantages to becoming an informer that the temptation is always close at hand. When it comes to constable checks, informers are permitted to lie. Now you can show any card rather than your highest of that suit — or even withhold playing a card at all. Of course, given this game’s emphasis on revealing your hand to the table, there are some risks. If you pretend that your highest sun-suited card is a four when everybody saw you reveal an eight just last round, well, the world is full of terrible snitches. But if you can pull it off, it’s possible to evade detection. You can bring the best cards to Mother Clap’s festivities without running the risk of having them confiscated.

Further, informers gain some leeway with the law. Near the end of each round, everybody contributes half of their cards to a single gossip pile. This functions much like the skill check in a hidden traitor game like Battlestar Galactica. The gossip deck is shuffled and revealed, at which point its contents will affect the molly house’s notoriety. Harsher penalties may be added to the bag. Worse, if the scrutiny grows too intense, Mother Clap’s will be shut down entirely. When this happens, everybody loses — apart from the table’s informers. Lest you become an informer too cavalierly, however, the inverse is also true. If outed as a rat by a fellow player, an informer may even be barred from future festivities, becoming an outcast among their community of outcasts.

There is a precedent to such a harsh endgame. The historical Mother Clap’s was shut down in part thanks to the efforts of a “thief-taker” and member of the Society for the Reformation of Manners who used his position to blackmail and extort those he caught — and who, it turns out, was pilloried and imprisoned for sodomy. The possibility of betrayal is crucial to what Kelly and Wehrle have crafted. Molly House not only shares in the joys of its protagonists, the relief they feel upon finding people like themselves, the necessity of companionship, even the joys of sexual expression. But it also carries their anxieties, fears, pettinesses, even their potential self-loathing. When one lives in a society that detests them, it’s impossible not to stay up nights thinking about why. After a while, maybe those reasons ring in the ears.

Far from producing a simple lionization, the result is a game that celebrates queer joy while also acknowledging the dangers and tolls posed to those who pursued it in the not-as-distant-as-it-should-be past. It centers people who have traditionally gone overlooked, and does so in a way that demands empathy and consideration. It shares in their apprehensions and terrors, joys and triumphs, loyalties and betrayals. It contemplates a moral question without indulging in petty moralizing, and certainly without the drab policing of its constables.

Even in its incomplete form, it has no parallel. Where so many games place necessary distance between themselves and their subject matter, Molly House bridges the divide. There will doubtless be many ways to discuss it: the visibility of its inhabitants, their victimhood, the systems and morals and individuals that isolated them from one another, the roots of our own modern puritanism. These are all valid, and I can’t wait to see them investigated and discussed.

For my part, however, my gratitude is more immediate. I’m glad to have played a game that makes love and sex as viable a thing to contemplate as war and murder and economic optimization. Not in a pornographic sense. Recall, I’m a class-four prude. Rather, in how it affirms that the hidden portions of ourselves are the bedrock of our tenacity, for they are the parts that must be shared to forge the tightest bonds. In accentuating that sharing — and in permitting its abuse — Molly House speaks to the tenderness that resides in all of us, and does so in the way that games are so uniquely capable of accomplishing within the magical sandbox of play.

Molly House is funding on BackerKit right now. You can find it here.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A prototype copy was provided.

Posted on October 17, 2023, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Cole Wehrle, Molly House, Wehrlegig Games. Bookmark the permalink. 11 Comments.

As usual, excellent write-up, Dan. I now face a conundrum: should I back this game and pay an arm and a leg for shipping to Brazil, or should I wait and hope it is published (just like the previous wehrlegig games) by a local publisher? I fear the game’s subject may be deemed too “controversial”/”woke” to be considered viable (not surprisingly, Brazil has one of the largests, if not the largest, crime rates against the queer and LGBT community).

Hoo boy, that really is a pickle, isn’t it? If I had a crystal ball, I would foretell the future for you. Since I don’t, I wish you the best in figuring out the best course of action!

Hi, Pablo! Fellow Brazilian here.

I think Wehrlegig has some sort of ongoing contract with Galápagos to bring their games here. For how much we love them, I think we can all admit Wehrlegig’s games are super dry and have close to zero mainstream appeal. It almost doesn’t make sense for Galápagos, a company that apparently makes most of their bank selling Dobble and Zombicide, to keep choosing to release localized versions of them here. And yet, we did get both Pax Pamir and (just this month!) John Company. So I’d say there’s a fairly good chance we’ll see Molly House as well.

That said, I guess our best options would be to vote with our wallets by purchasing both Pax Pamir and John Company.

There’s also the “ask Cole Wehrle directly” route. When John Company was in the process of shipping to their initial backers in the US, I asked him on BGG and he kindly confirmed there were localization efforts in place. That was when I knew I could wait to get the game in Portuguese. Mind you, this was around one year before Galápagos would make any announcement about the game.

Fingers crossed!

Sounds like another home run from Wherligig Games. What a fascinating topic, thanks for the write-up.

Thanks for reading, Christian!

“For my part, however, my gratitude is more immediate. I’m glad to have played a game that makes love and sex as viable a thing to contemplate as war and murder and economic optimization. Not in a pornographic sense. Recall, I’m a class-four prude. Rather, in how it affirms that the hidden portions of ourselves are the bedrock of our tenacity, for they are the parts that must be shared to forge the tightest bonds. In accentuating that sharing — and in permitting its abuse — Molly House speaks to the tenderness that resides in all of us, and does so in the way that games are so uniquely capable of accomplishing within the magical sandbox of play.”

Man, you are good with words. This paragraph alone made the read worthy even if I never come close to this game in my life.

Thanks, syvfingre!

Dan,

Just wanted to say thank you; I really appreciate your write up and your perspective. Truly amazing what games are doing these days from this to Stonewall Uprising to Kaiju Table Battles. Thank you for shining a light on these games and their incredible developers. And for providing a critical lens on what these pieces of art are saying.

I have a family member who works in Sexuality and Gender Studies and I can’t wait to share your write up with them.

Thank you for the kind words, Craig!

Pingback: October 22nd – Critical Distance

Pingback: SDHistCon 2023 | SPACE-BIFF!