To the Waters and the Wild

It’s a rare game that saturates itself with a sense of loss. Defenders of the Wild is one such title. Both a lament for the natural wonders we so readily pave over and a defiant yawp in the face of automation and progress, there’s an optimistic romanticism to the whole thing.

Perhaps that shouldn’t be surprising. T.L. Simons previously designed Bloc by Bloc, another supernal game about staring down systemic oppression. Now he’s joined by Henry Audubon to take the fight to the fields. It’s not as great a jump as one might assume. Put them together and the combination produces a rallying cry: Bloc by Bloc for the urban populace, Defenders of the Wild for those who see their way of life being swallowed up by enclosures. The whole thing has the tone of a fable. A fable about slagging robots.

I couldn’t tell you who assembled the robots that are now chewing through the woodland, but the scars they stitch into the landscape will take lifetimes to mend. There’s a stark contrast between this game’s two halves, and it’s the robots who draw it.

The game dawns on a near-pristine woodland. The map is divided into colorful hexes that nonetheless merge into coherent swaths of terrain. These generate paths for your protagonists. While playing as the motley band of animals that constitute the yellow team, for instance, you can glide along and through grasslands like a highway; likewise for purple’s mountains, teal’s wetlands, and orange’s autumnal glades. The feel is naturalistic, sometimes producing wide trackways for your animals to traverse, while at other times tucking away little valleys or lakes in hard-to-reach corners. There are textures to this geography, essential imbalances that define the places you can or cannot easily reach, which regions will be tougher to defend, and the routes that will sting when broken apart.

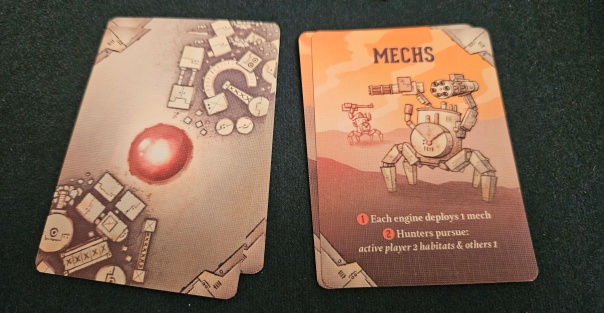

Because that’s what the robots do. They break. They see this landscape the way a broken serger might see a wrinkled tablecloth. The artificial opponent Simons and Audubon have produced is a horrible wonder, a simple system of only six repeating cards that nevertheless pursues its objectives with impressive violence and a mechanical disinterest in your wellbeing. The first harbingers of that process are two towering engines. You cannot pass through these any more than a squirrel could pass under a running lawnmower. Worse, they deposit steel barricades in their wake, crisscrossing the landscape like a terrible zipper. You also cannot pass through these. Until you blow a hole in them, anyway.

From there, the machines gradually zip up entire hexes. These are transformed into factories. Like the machines’ original starting place in the center of the map, these produce further robots and pollution. The first exist to snipe at your passing wildlife or pursue them to the fringes, while trash piles together until it poisons anybody nearby. Before long, entire segments of this once-bounteous wild have been transformed into a tangle of impassable walls, heaps of toxic slurry, and patrolling drones.

There are so many ways to lose in Defenders of the Wild. Pollution, factories, injury — all threaten to scuttle your uprising before it can fully organize. This is one element of the game’s fable, a cautionary tale about the many risks posed to activists who face a machine with centuries of practice under its belt.

Much like Bloc by Bloc, however, this fable also contains a step-by-step guide to fighting back. It begins with organization. Each player begins with a single camp on the map, a power base for producing items and to which they can flee in times of need. It will take many more such camps, all pitched in friendly terrain, and only after amassing enough support. This is built by blowing up robots, cutting through walls, sweeping up trash — in effect, matching your talk with walk.

As games go, this is all straightforward stuff. Running the resistance is an exercise in managing risk and resources. Each turn opens with everybody at the table selecting a single card, which spells out how many actions you can take and which special ability you’ll have at your disposal. In one round, you might be immune to sniper attacks, letting you skirt the edges of a factory without putting yourself in harm’s way. The next, maybe you’ll begin by giving everybody at the table an item or claiming the first player token.

Those items, by the way, are this game’s equivalent to mutual aid. Each team offers its own item, which is shared and gifted between factions. The creatures of the wetlands produce healing salves, while the mountain-dwellers assemble rockets for busting robots from afar. Cooperative games have always walked a tightrope between too much collaboration and too little, and Defenders of the Wild strikes a delicate balance. Your cards are your own, preventing any one player from commanding too much authority over everyone else. At the same time, your advantages tend to be mutualistic, doling out bread and maps and other perks to your fellow resistance members.

Either way, collaboration is essential. Your ultimate goal is to deploy all your camps and then smash the enemy’s factories. This is usually a painstaking process, not to mention a painful one. Such an endeavor requires that the factory walls be breached and the robots and pollution within cleared away. All the while, you’ll be taking hits and dodging hunters. So it behooves you to divide duties with your allies. One team moves in and breaches the wall and clears away any nearby hunters. Someone else goes in and ensures the toxic spills are cleared. Finally, a third squad delivers the killing blow, returning the factory to nature and capping the venom leaking into the soil. There’s plenty of wiggle room here, but it’s a process that requires both adaptability and coordination. The alternative is a slow choking death under a mountain of trash or the heel of a hunter-killer.

Sometimes, anyway. If I had one complaint with Defenders of the Wild — or with the prototype version I’ve been playing — it’s that there’s a wide difference between too tough, too easy, and just-hard-enough, and the game’s artificial opponent doesn’t always find that sweet middle spot. T.L. Simons and Greg Loring-Albright previously confronted that problem in the third edition of Bloc by Bloc by positing that one of your allies might be an opportunist looking to capitalize on the city’s unrest to propel their faction to sole power. If the city’s defenders didn’t put up much of a fight, perhaps your so-called friends would.

By contrast, Defenders of the Wild plays its cards straight. This eases the game’s cognitive load and produces a statement that’s more singular, not to mention entirely friendly to outsiders who don’t know (or don’t want to know) anything about the Tragedy/Fallacy of the Commons or how enclosure steals from the public to enrich the few. Here the fable is principally procedural. To succeed, you must politick and pound pavement, both metaphorically and literally. You’re shown point-blank how open terrain can be sewn up, preventing free movement and leading to urban flight. In one sense, both games combine to generate a single argument, demonstrating how one crisis leads to another, the troubles in Defenders of the Wild sparking the troubles in Bloc by Bloc.

You’re also shown that the answer to systemic problems cannot always be systemic. How could it be, when the system is arbitrated by those who benefit from its imbalances? The machine simply will not listen, no matter how eloquently your animals chirp and chitter. Sometimes the only solution is to violate a hedgerow and torch a manor. Pardon me; the solution is to blast a robot and rewild a factory. Although these days, those statements are equivalently political.

But those are hefty discussion points. Like I noted earlier, Defenders of the Wild is entirely happy to let its messaging operate at the level of fable. The result is a charming but razor-toothed game, one that slaps a sterner face on the anthropomorphic woodland creatures craze that’s been going around. Its highs are considerable, letting players revel in the vicious comeuppance of woodland creatures against their mechanical oppressors. Whether playing with my nine-year-old or a group of adults, I’ve been having a heck of a time smashing the machine.

Defenders of the Wild will be on Kickstarter tomorrow. Here it is.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A prototype copy was provided.

Posted on September 25, 2023, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Defenders of the Wild, Outlandish Games. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

Sounds great, I need to check this out.

Cooperative games need a way to curb quarterbacking. Is “everybody has their own cards” really enough?

I personally regard quarterbacking as a player problem more than a game problem, so I might be the wrong person to ask.

Yeah, I kind of feel it is like saying, competitive games need a way to curb whining. Is whining a game ruining behaviour for me? Yes. Is there anything games can do about it? Not much. The players need to hash that one out.

A lot of unpleasant competitive behaviours are addressed by game playing culture. I think the issue with coöp games is that the culture just has not yet caught up to the innovation of playing with different win conditions other than pure competitive (note, game playing culture also has difficulty navigating all lose or one win).

My personal gripe is with coöps that can only be played by committee (Freedom The underground railroad is the classic example for me) because of the level of coördination required. That for me is just a solo game that has been mislabeled (mind, I feel the same about competitive games without pertinent interaction, mislabeled solo games).

A gameplay video really reminded me of Pandemic. And I don’t enjoy Pandemic very much. Does Defenders feel like Pandemic at all?

Hm, I don’t really see the connection. At a broad level, though, it’s the same “genre” as Pandemic, the cooperative game where you’re putting out fires but they’re cropping up a little bit faster than you can comfortably handle.