One Minute to Stationfall

I don’t remember how it came up. Andy Mesa, the principal developer on Matt Eklund’s Stationfall, mentioned that this was the logical endpoint of all those fancy patented techs in Pax Transhumanity. I can see it. All these advances, yet we still cut corners on the station’s construction codes. This is a place where heavily armed security bots brush elbows with sentient chimps and telepathic rats, where botanists and schizophrenic doctors chase patents of their own via research most unethical, where a billionaire has taken up residence across the corridor from the maintenance clones. And it’s falling out of the sky.

That billionaire, by the way, is the source of Stationfall’s least-subtle but best joke. But to understand it, you first need to onboard some basics. And what better way to do that than by hearing the tale of the time my best buddy was kidnapped?

Twelve minutes to stationfall.

That’s the alert we received, broadcast wide across all spectra. Humanity’s first luxury-slash-research-blacksite space station, the product of a trillion credits, indomitable, would soon be slagged by reentry into Earth’s atmosphere. A disaster that would be remembered alongside that of the Titanic. Not in terms of human casualties — there were only a dozen of us aboard, and truth be told few of the wretched masses below would spill tears over our demise — but because the designer had decided to spit in the eye of Darwin by naming the dang thing Titanic. O hubris! O where is the nearest escape pod!

In Stationfall, every minute is a single round. There’s an immediacy to the whole affair, aided in part by the game’s willingness to label everything. The Eklunds, both Phil and his more-hinged son Matt, have always filled their games with nouns and verbs. Sometimes to their detriment, as anybody who’s wrestled to remember the in-game function of antioxidants or menopause can attest. Here the labels act as both form and function, mnemonics as well as flavor. “Twelve minutes” is evocative in a way that “twelve turns” is not.

That goes double when you need to accomplish so much in so little time. Every session of Stationfall opens with an amount of information equivalent to a handful of sand stuffed under your eyelids. The station map is sprawling, over thirty spaces with unique actions to consider. There are twelve to twenty characters in play, each with their own actions, bid requirements, reveal opportunities, scoring menus, and buddy bonuses. When I teach the thing, I encourage first-timers not to worry about the fine details.

Such advice is folly. This is a game that begs, nay demands, that you focus on everything all at once. You’re only in control of one character among those twelve to twenty. But that’s not quite true. The beauty of Stationfall, the crushing joy of the thing, lies in its sheer willingness to clobber you with data. The effect is not unlike panic. Say, the panic of hearing that in twelve minutes your atoms will be strewn across the planetary atmosphere. Because in Stationfall you aren’t only playing one character. You’re playing all of them.

Here’s one way to frame it: Stationfall is a bidding game. Every turn begins with an investment. You’ve heard that the station is in freefall, so you scramble to enact your plans. In your possession is a hacked tightwave. You can call up anybody and issue them orders. Hey Troubleshooter, head over to the mainframe. Colonel, I order you to access the security station and flip off the jammers. Listen to me, Microbiologist: the only way to save your hide is by ejecting the antimatter core. Trust me.

In the process, your character — you — may well be ordered to act against their best interests. There are ways to prevent this. You could reveal yourself to the table, a devil’s bargain that unlocks access to your strongest actions and prevents others from influencing you, but also tapes a big kick me sign to your hindquarters. Or you could simply pile influence cubes onto your character, pricing other players out of utilizing your actions. That, too, is often a signal that such-and-such character matters too much to you. At that point, your rivals might figure that it’s better be safe and vaporize them. Vaporize you.

Seven minutes to stationfall.

Those first minutes were fraught. Everybody running aimlessly, scooping up spacesuits and kompromat and suspiciously hefty wrenches. There was no discerning anybody’s aims. Most were bent on survival, sure, but every so often somebody just looked at you wrong. The Station Chief was going all Ahab, shouting about how everybody needed to escape while she went down with the ship. A Cyborg was on the loose, braining everyone in his path, while the Botanist was apparently grinding the bodies into fertilizer for his pet plant. The Legal Robot was blocking access to the escape pods until everybody signed non-disclosure agreements. Not now, little dude.

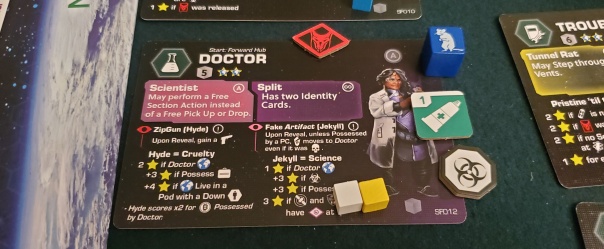

And then there was the Doctor.

Look, we’re neuro-acceptant here in the future. When we say the Doctor is schizo, we don’t mean it negatively. It’s a term of endearment. She’s a system, you see. Two minds, one body. Her brain is hyper-efficient, which under normal circumstances makes her an excellent station doctor. She can give you a second opinion like that. It’s not her fault that her consciousnesses have divergent aims. We don’t judge.

Or we didn’t. Because when the Doctor manipulated the Cyborg into smacking the Engineer in the cranium, and then dragged his unconscious body into the medevac pod and launched it into the mesosphere, cackling about how she now had a human receptacle for furthering her diabolical surgeries — “diabolical surgeries” was her phrase — friend, we started to judge.

Everybody in Stationfall has their own goals. Often they have an entire laundry list of goals. Putting them into action resembles a heist film, rapid cuts between collaborating characters and all. In this case, the player who we now strongly suspected was the Doctor — and more specifically, her Mr. Hyde personality, since she comes with two competing identity cards — had expertly manipulated the situation to her advantage. She had lured the Engineer down to the forward airlock, bribed the Cyborg to cut a path through the lower station, brought the two into sharp collision, and then dragged the Engineer’s damaged body into the medevac shuttle, bypassing the need for the station to properly undock its escape pods. Only a few minutes into the game, she was bound for Earth.

Which is a frightening proposition. No, not because the Doctor would soon be attempting her reverse kidney-stone procedures on the poor Engineer. Rather, because that gave her a whole seven minutes to mess with the rest of us. This is the part where Stationfall morphs into something like a social deduction game. If you can ascertain your opponents’ identities, you can spanner their plans. Sometimes this is as simple as influencing a character to step out of an escape pod seconds before it launches. Other times it’s tougher. Like when the Doctor called up to the station to have somebody jettison the antimatter. Presumably she was able to disguise her evil cackling over the radio, because her quarry went and obeyed. Now the station was on the verge of total destruction. In four minutes instead of seven.

Four minutes to antimatter implosion.

Shit.

There isn’t enough time to get everything done. That’s a common newbie complaint in Stationfall. And, really, there isn’t. That’s part of the point. Stationfall is madcap comedy. Slapstick. You make a plan and it fails. Maybe somebody else moves a crucial character out of the position you painstakingly moved them into. Maybe a rival steps out of the shadows and shoots you in the face.

Or maybe the entire table conspires to stop you.

That’s what happened now. With the antimatter out of containment, there simply wasn’t enough time for everybody else to pursue their objectives. Our best hope was to bring the Doctor down. This could be interpreted as somewhat gamey. If we were actually the last-second victims of a collapsing space station, would we really care that the Doctor possessed more victory points than us? I’m not so sure we wouldn’t. In a way, working together to get revenge is the most human response to discovering that somebody has been the architect of your demise. Although we might not interpret it as “victory points,” a mad doctor escaping as the station exploded behind her was cause for some vengeance.

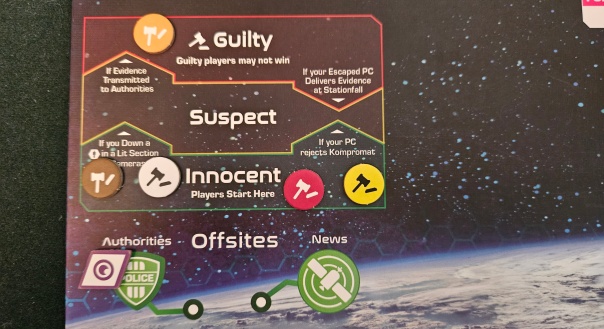

We couldn’t reach her. The medevac shuttle was already jolting through the mesosphere. But we could report her activities to the authorities. In Stationfall, players can’t attack one another willy-nilly. If the station cameras are still on, committing certain activities in an observed room, assault and murder among them, will mark you as suspect. This in itself isn’t a problem. When the insurance adjusters comb through the wreckage, individual misdeeds will likely go overlooked among the tangle.

But. But. But. If somebody goes to the trouble of accessing station security and transmitting crystal-clear evidence that the sole survivor programmed the Legal Robot to remove the antimatter from containment? Yeah, that might stick. This bumps that player’s status from suspicious to guilty. Now they’re barred from winning.

After a quick pep-talk, that’s exactly what we did. The Doctor was still trying to block us. She directed the Cyborg’s rampage with renewed intensity. Meanwhile, the rest of us hustled to enact two plans at once. While some of the characters worked to get the antimatter off-station, the rest of us bounced data packets around. In addition to carrying up to three items, characters can store data. In this case, we had the Station Chief retrieve evidence of the Doctor’s wrongdoing from the security station, lower the jammers, and transmit it down to the Counselor in Array Control, who in turn beamed it to the authorities. The antimatter detonated outside, wrecking the airlocks but otherwise leaving the station intact. And the EarthCops announced that they would take the Doctor into custody as soon as she landed.

We had won. If only the Doctor had received the memo.

Four minutes to stationfall. Again.

With the station’s orbit once again decaying at its previous rate, our fragile alliance was dissolved. Somebody switched off the lights and the Astrochimp scampered through the vents to murder the Daredevil before she could perform her death-defying dive to Earth. The Legal Robot resumed handing out NDAs. The Troubleshooter repaired one of the broken escape pods and sent it limping to the surface.

And the Doctor commanded her agents to unleash Project X.

Every session of Stationfall has a Project X. Chances are that you won’t know what it is. Only a choice few characters begin with the knowledge, and by suborning them you can learn what the vault contains. In our case, nobody had been interested in cracking the lid to peek inside. Often, it’s a bad idea. Project X can take many forms, among them a Tentacled Monstrosity, a Robotic Assassin, or self-assembling Grey Goo. None of which, as you can imagine, are conducive to escaping the station. We were already suffering through one Pandora’s Box. Why open another?

The Doctor knew what it was. She began the game with the knowledge. Presumably because she’s been poking it with needles. While the rest of us were busy up-station trying to board the escape pods, she had free reign to crack the vault. No problem. The monster probably couldn’t catch up to us anyway.

Except what emerged wasn’t a monster. Not in the traditional sense. It turns out the station’s top-secret project was… a death ray. Which the Doctor’s hapless volunteers immediately discharged into the atmosphere. The ray sizzled past the Troubleshooter’s pod, even past the Doctor’s medevac. Instead, it struck EarthCop headquarters. “Smoke’em pigs,” the Doctor cackled.

So much for her arrest.

One minute to stationfall.

We were doomed. Oh, some of us escaped. Others died on the station but hardly minded. The Station Chief perished with a petrified smile of satisfaction on her face. Legal Bot booped his last boop, happy to have printed off so many NDAs. The Stowaway, a child, who we had mostly ignored the whole game, died as she lived: with nobody much noticing.

When Stationfall comes together, it’s a thing of beauty. That beauty is the opposite of elegant, closer to a thicket or a quip-a-minute comedy than, say, a vase. A full session feels like a good improv, packed with “and then…” moments. Every beat unfurls new possibilities. In one of our plays, every single person escaped because Project X turned out to be a stable wormhole leading to a research base Earthside. More often, the station breaks apart filled with corpses and screaming sociopaths. Even more often than that, you get a mix of both survivors and victims. I’m not sure I’ve laughed more during a board game than in certain sessions of Stationfall.

It can also be disappointing. Rules are easy to misplace, and it’s a rare session that doesn’t kick up at least one stumble. I wouldn’t call its rulings ambiguous, but there are a hundred edge cases that feel ill-defined until you realize they’re covered somewhere. It also sometimes swerves into the frustrating. Going last is incredibly powerful in the endgame, creating bullshit moments like the aforementioned “Oh, your character stepped out of the last escape pod at the last possible second. Soz!” If you can’t roll with the punches, including plenty that land below the belt, Stationfall isn’t the game for you.

And there are times when it’s all of these elements at the same time. This session concluded with such a moment. When the Doctor stepped out of the medevac shuttle, she was not arrested. Thanks to the death ray, there was nobody left to haul her away. She did the hauling, dragging the Engineer off to conduct her diabolical surgeries. Her words. Not mine.

I lost because of the Engineer’s fate. He was my buddy. At the beginning of the game, everybody draws two characters and chooses which one they’ll embody. The other one becomes their buddy. (They’re actually called “bonus characters,” a term that doesn’t fit with the game’s devotion to nouns that suit the setting. “Buddy” works better.) According to the icons on the bottom of your buddy card, you either want to help them escape or ensure they burn up upon the station’s reentry.

Here’s the twist. The Engineer was my buddy… and I very much wanted to ensure that he died. You would think, based on the fact that he was abducted by a homicidal doctor, that his non-survival was guaranteed. That’s what I thought. But because he was successfully evacuated to Earth, he counts as a survivor. It doesn’t matter that his kidneys will soon be swollen with calcified salts. It doesn’t matter that he will beg for the soothing release of death. He is a survivor of the station’s fall. That’s all that matters.

So I lost. My main character’s identity hardly matters. To me, this was the story of how the Doctor played us all like a cat-gut fiddle. And the outcome was a mixture of emotions. Frustration, because the outcome relied so heavily on the particulars of the game’s not-always-intuitive rules. But also elation, dizziness, some very loud laughter. Because there’s nothing quite like this game’s slapstick, or the insane workarounds it permits, or its story-generating improv. The closest touchstone is probably Vlaada Chvátil’s Space Alert, another game that understands that failure can be as satisfying as success, and is nearly always more amusing. Stationfall is at its best when you’re either winning or losing. When you’re somewhere in the middle, bogged down in the rules or outright lost amid the bustle of so many characters and so many systems, that’s where it flounders. I don’t know who originally called it a party game for heavy gamers, but that’s as apt a description as there’s ever been.

Now, at last, you can understand the joke behind the Billionaire. Like everybody else, the Billionaire might become your buddy character. Except you aren’t interested in either killing him or saving him. Because nobody really cares about billionaires. Instead, his buddy rule is the sole exception to the game’s usual rubric. When he’s placed on the map during setup, somewhere on the station there is a Space Pug. His prize pup.

If the Billionaire is your buddy character, you must save the Space Pug. That’s it. Like everyone else, this informs the texture of the game to come. Now characters might find themselves punting the Space Pug between one another, doing their darnedest to save the wheezing thing. Or else jettison it into space, where it floats quite happily in its little space suit, waiting for somebody to pick it up again.

That’s Stationfall. There’s nothing like it. For better and for worse. But mostly for the better.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

Posted on September 6, 2023, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Ion Game Design, Stationfall. Bookmark the permalink. 14 Comments.

It is cool to see how this game has come along, I remember playing the prototype with you on TTS in early pandemic days!

I remember! I played this one so many times via TTS. I still haven’t caught up with the physical copy. In some ways the TTS version is superior, since you can zoom in on all those character cards without having to crane over the table.

Glad that you like it. To me it’s an excessively complicated, chaotic, unteachable, exceptions-riddled, uncontrollable blob with insufferable downtime that you play with the rules over your head for quick access.

Sorry to hear it! I imagine that’s how it will shake out for plenty of folks.

Your verve, Dan, is unequaled, and your description of the game gives it an extraordinary breadth, almost epic in scope. Indeed – and Andy understood that perfectly – the game has to be considered from a large perspective to be appreciated. From a narrow perspective, that of your “own” character and objective, the game is desperately shallow. You can select this character who needs to take a suitcase and leave in a pod. If that, alone, is not underwhelming, the Space Pirate might just kill him before you even get to move him. You then spend 12 turns trying to revive him, only to see him killed again on the following turn. And try to convince the table that this was not “your” guy. No, the game only exists in the wider perspective of the entire table. The question, then is whether the game’s “emerging” narrative is a brilliant, epic and fascinating enactment of the group’s collective mind, or the equivalent of asking an AI to paint a Rigatoni fight between anthropomorphic animals inside a school cafeteria in the style of Jean-Honoré Fragonard. I think the latter: like a cadavre exquis, its nonsense is hilarious. For exactly 10 minutes.

I can see how some people would be unhappy when they find out they are not the main character in the story.

Others are just happy to hear the story.

Dan (who for me is the best reviewer in the business) wrote a brilliant piece on the game which is a pleasure to read. As I said, I am glad he liked it. I think that for the right people, as you say Andy, this can be the epic sandbox that he described. It’s this kind of game that you either find marvelous or insufferable.

I’m a big fan. We don’t play it as often as I would like because you need to have the right group. Get a group of smack-talking friends who don’t take winning seriously and this is like playing an epic game of Space Station 13 on the table. If you’re a super casual gamer or an intense euro gamer this is probably not right for you. If you can have some fun with insanity that requires a touch of tactics this is a fantastic and very unique board game.

I think SS13 is a very apt comparison, and Stationfall may as well have been called Space Station 14: The Board Game.

The worst part of that is that nobody I know knows what SS13 is, so I can’t use this comparison to succinctly describe what Stationfall is about 😦

I considered using SS13 as a touchstone in the review, but I figured nobody would know what I was talking about.

I see Andy Mesa in the comments, and well, not sure if he will read this too and want to answer, but – the situation with MasQueOca was solved in any way? As in, either by patching things up or by you guys deciding never to deal with them again?

For those that dont know, the problem was that the manual on the Spanish edition removed a description of a character saying what pronouns they use. When asked, the guy at MasQueOca (not sure what position but high) responded that yes, he removed that to “stop that madness”. And of course a healty debate ensued… well, no, the opposite of that.

Right now I have MasQueOca in my banned list, which sucks given they got some very interesting licenses, but the whole thing soured me on them (and also on some acquaintances)

In any case, I’d like to test this game a bit more, I played it once on TTS and not fully, and it really left me with conflicting feelings. Looks like a beast to learn and teach, looks like a chaotic rumble that may generate fun tales like yours, Dan, or just collapse in a mess, depending on many factors like who plays and what happened, but also looks intriging and precisely that potential for a good tale is alluring.

Not to speak for Andy, but he isn’t with Ion anymore, so I don’t know if he has any details to share. I know he was frustrated when MasQueOca decided to censor the game.

I’m glad you brought it up. Even though it’s beyond the scope of this review, that’s a useful detail for anybody who might be interested in the MasQueOca edition of the game.

Sounds a tiny bit like 10 Minutes to Kill, too, in terms of the “you do stuff with lots of characters but only one is actually you”

Pingback: Best Week 2023! Making Memories! | SPACE-BIFF!