Greenwashing History

[Content Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following article contains images of people who have died.]

Back in June, the Utah Board of Education delivered five pages spelling out exactly what educators could (and could not) teach on the issues of race and racism. The inciting topic in the Utah Senate was — surprise, surprise — Critical Race Theory. The debate had been perfunctory. One side was staffed by professional historians and veteran educators. The other consisted of angry parents who insisted they’d heard firsthand accounts of teachers berating white children.

After producing neither any berated children nor a definition of Critical Race Theory — “It’s like a gas,” one sponsor noted — the Senate determined that the theory was probably anti-American. “We need fact, not theory,” insisted one signatory.

An admirable sentiment! Apart from the pesky detail that those supporting the resolution not only lacked a definition for the theory they were determined to blacklist, but also didn’t have a definition of history. Because while history collects many facts, history has never itself been a fact. History also brims with theories, but is not quite a theory.

History is a war.

I. Three Boys Wade into a River

Mormonism has a weird relationship with Christopher Columbus. Buckle up, because this is going to require some explaining.

Growing up Mormon in Utah fosters a keen connection to history. As a child attending Sunday school, we sat on the floor to get a sense for the “pioneer experience.” Because pioneers didn’t have chairs, you see. With toothpicks for spokes, marshmallow wheels, and graham cracker headboards, we fashioned handcarts and wagons, sang songs about gathering buffalo chips to fuel our campfires, and listened to the story of how three eighteen-year-old boys rescued the wintered-in members of the Willie and Martin handcart companies by carrying everybody across the frozen Sweetwater River. Not long afterward, our teacher said, her voice low to signal that she was about to tell us something reverent, those three boys died. But they died having saved all those souls from freezing. Surely there was no love greater than this.

Something settled over me. A shiver, a warmth. A courage. Years later, when I learned that those three boys had been spread across a range of ages, only carried a small portion of the five hundred pioneers across the Sweetwater, and lived long and healthy lives afterward, my feelings were more complicated. After some disbelief, some reckoning, and some bitterness, I finally settled on — well, why did they have to die to make the story better? They still saved people’s lives, didn’t they?

This is adolescence and, eventually, adulthood in Mormonism. Given enough time, it touches everything. Every story. Every practice.

Like attending a family reunion for the long-dead polygamists that hang in black and white on your grandparents’ wall. The opening prayer thanks Heavenly Father for your “noble blood.” Afterward, Mom leans over and whispers, “Don’t let it go to your head. Nobody’s blood is noble.”

Like being taught that a vague prophecy in the Book of Mormon was about how Christopher Columbus was inspired by the Holy Spirit to cross the Atlantic Ocean to bring the wrath of God upon the Natives Americans. Except this is portrayed as a good thing. Because the Native Americans were the descendants of the Lamanites, the antagonists of the Book of Mormon who rejected the Gospel. Never mind that Joseph Smith wrote as his church’s second article of faith, “We believe men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgressions.”

The arithmetic behind that distinction isn’t hard, especially rooted in the racial assumptions of the 1830s. Some people have noble blood. Noble blood doesn’t transmit sin. Others have indecent blood. Mixed-up blood. Mutt blood. Black blood. That blood deserves to be spilled for the crimes of people five centuries dead. If they ever existed at all.

Here is what I mean by history being a war.

As an adult, I listened to a Sunday school teacher praise Christopher Columbus. “I reject the revisionists who would tarnish the reputation of that noble man,” he said, finger stabbing at some invisible foe. Noble! Could we be thinking of the same person? The same Columbus who birthed the modern slave trade when he shipped five hundred Taíno back to Europe? Whose governorship saw the depletion of a third of its population, not only from disease and starvation, but also from brutality? Whose punishment for failing to accumulate enough gold for his ships was the dismemberment of unworking hands? The same Columbus who was imprisoned and stripped of his governorship by the same royal couple who instituted the Spanish Inquisition, under charges of brutality, slavery, and tyranny?

Noble! If this is the same nobility that courses in my own blood, I want none of it.

Don’t get me wrong. As a historian, I’m always wary of presentism. Checking my modern standards at the door when it’s time to evaluate past subjects is nothing new. I’m also fully aware of the “black legend,” the counter-Spanish and anti-Catholic propagandizing that became all the rage in Europe. Even as the Spanish extended the first protections to the indigenous peoples of the New World — in part because of their horror at Columbus’s abuses — their global image withered beneath a broadside of exaggerations, omissions, and fabrications.

Even this context, however, completes an unfortunate circle. Because the insults reserved for the Spanish had little to do with their overseas empire. According to the day’s writers, they were insular, superstitious, obsessed with personal honor, lacking in both empathy and taste — and crucially, they failed to meet the standard of being sufficiently European. Students of Orientalism will find these traits distressingly familiar. The principal crime of the Spanish had nothing to do with tangible offenses. Rather, it pulsed beneath the skin, mingled with the Moors during centuries of occupation.

Blood. In this case, blood a little too black.

When a professor at Brigham Young University, Mormonism’s largest educational institution, penned a hagiography defending the explorer, great care was given to the testimonials of those who knew Columbus, citing his leadership at sea, his talented navigation, his faith in God. When those same sources later outed him as a tyrant, our latter-day historian declined to relay their words. Please note, nothing this professor wrote was unfactual. It was pruned. Carcasses dutifully swept aside, all that remained was the statue of a noble man.

There is no such thing as “just the facts, ma’am.” Not with a subject as sprawling and complicated as history. Instead, we have models — always incomplete, always flawed, always myopic. Because models are all we have, truth is an approximation. And our best method for uncovering that truth is by pitting those models and interpretations against one another. Time and evidence and argumentation gradually sharpen these models. I suspect this process will never be complete.

This is one way in which history is a war.

Yet there’s another, more immediate sense. Because history is about smashing models and interpretations against one another, good history is by its very nature uncomfortable. Old, accepted ideas splinter as they’re tested against new evidence and new models. Therein lies the real war. Comfort versus discomfort. The easy road versus the winding bog. Heroes versus humans.

Comfortable history is easy. It exists to buoy our feelings and placate our desire for improvement. It is devoid of confrontations with the self or with society. And it is so shot through with omissions that it can barely hold its own weight, let alone the burdens of our expectations and identities. By some twist of irony, the fraught path is more secure. By embracing the messiness of history, we begin to see people instead of statues. Our idols are thrown down. So, too, is our reliance on them. Relieved of the burden of defending the indefensible, history becomes ours, a wellspring of lessons and warnings.

Mormonism was essential to my own immersion in history, but it doesn’t stand alone. Whether we’re talking about the worst excesses of religion or national tall-tales or state propaganda, myth-making is one of our oldest vocations. It births all of us into an ongoing war. Tidy but incomplete stories stand on one side. Rich but discomfiting history stands on the other. An easy choice, if only the soldiers of the first side weren’t so militant in safeguarding their bedtime stories. Critical Race Theory has become the latest battlefield — a bewildered conscript, given its absence from any modern educational program that isn’t law school. But it’s hardly the first, and it won’t be the last.

Look, I know what you’re thinking. “What does this have to do with board games?”

Would you believe everything?

Today, we’re looking at two board games by Martin Wallace. Set in the same “cinematic universe,” both titles employ the same technique to make their historical subject matter more palatable to players: greenwashing, a process by which historical figures are cast as literal aliens in order to expunge any guilt the player may have felt upon killing them. In these games, this greenwashing is tied directly to the works of H.P. Lovecraft. By now, Lovecraft’s personal and literary racism has been well documented, and in recent years there has been an effort to reclaim the genre of cosmic horror from its racist origins. In the case of Wallace’s games, this racial dynamic shouldn’t be forgotten. As we will see, it plays a non-negligible role in how greenwashing can transform its targets into victims.

Over the course of this discussion, I hope to expand on three motifs. First, that history is a war. Second, that the deadliest weapon in this war is erasure. And third, that the racist delineation between noble and savage blood is a recurring and intractable element of this war, whether consciously or unconsciously.

II. Their Blood Was Ichor

In Martin Wallace’s 2013 title A Study in Emerald, based on Neil Gaiman’s short story of the same name, things are not as they should be.

As of 1882, the Old Ones have occupied Earth for seven hundred years. For an alien occupation, this new normal looks shockingly like our own 19th century: the Old Ones rule as monarchs and despots, and the same anarchic figures who struck fear into our timeline’s royals are now determined to toss grenades into their passing carriages — albeit in the name of “restoration” to human rule rather than a revolution favoring anarchy, socialism, or constitution. Oh, and because the Old Ones are translated straight from the works of H.P. Lovecraft and his imitators, there’s a miasma of fraying sanity going around.

Transforming Europe’s royal families into alien invaders is a thin but effective shroud. One doesn’t need to squint too hard to see that the green mascara hasn’t been caked on too heavily. The geography of Europe has been preserved along with its central actors. London is ruled by “Gloriana,” one of the nicknames for Elizabeth I. The mummified pharaoh-inspired Nyarlathotep has helpfully settled in Cairo and spends his evenings strolling among the pyramids.

On a more human scale, players are given secret roles as either “restorationists” or “loyalists” — roles that map almost exactly to history’s revolutionaries and reactionaries. Each player is given a name from the days of the week, calling to mind The Man Who Was Thursday, G.K. Chesterton’s satirical retelling of the Old Testament’s Book of Job, in which a policeman goes undercover in an anarchist organization only to discover that the other anarchists are also double agents working for the government. In both the book and the game, players initially have little clue whether their fellows are working to unseat the monarchy or entrench it by having their coconspirators imprisoned or killed. This sense of paranoia is appropriate. In many cases, the violent acts of 19th century anarchist cells were encouraged by undercover police, whose superiors were all too happy to permit the murder of minor functionaries and interchangeable ministers if it gave them something to pin on the organization’s higher-ups.

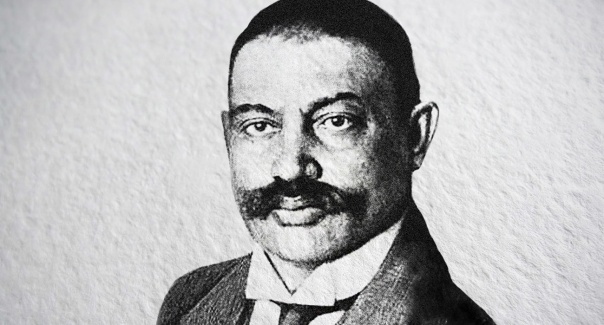

Here’s a prime example. The above image shows a portion of the cards that can be acquired to players’ decks in A Study in Emerald. This is only a small selection, but I’ve chosen these cards to represent the game’s loyalists/reactionaries. The card on the bottom left is Yevno Azef. Azef is a type of card called an agent, which means that upon acquisition to somebody’s deck, that player also places a token on the map to represent Azef himself. Azef is notable because he’s one of the few agents in the game who can assassinate either royalty or another agent. The former is the ultimate goal of the game’s restorationists, exchanging spilled ichor for a large quantity of victory points. The latter can be undertaken by either side — removing rival agents from the table is never a bad thing — but it only scores points for the loyalists, as their goal is to cripple the restorationists.

Azef’s flexibility as a game counter is appropriate. As a young man, Azef contacted the Okhrana, the secret police of the Russian Tsar, and offered to betray his fellow students for money. Over the course of his undercover career, Azef became the right-hand man to Andrei Argunov, one of the leaders of the Socialist Revolutionary Party of Russia, only to betray him to the police. He was eventually made deputy to Grigory Gershuni, head of the Party’s combat and terrorist organization. Upon Gershuni’s arrest, Azef became the head of the organization. In that position, he spearheaded multiple assassinations. The most notable were the bombing of Vyacheslav von Plehve (the director of the emperor’s police and the one responsible for authorizing Azef’s infiltration in the first place) and Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, the Tsar’s beloved uncle.

Which is to say, Azef became both the most dangerous terrorist in Russia and the Okhrana’s best-paid double agent.

These are the acts portrayed in A Study in Emerald. Behind nearly every card lurks violence that’s often actualized on the table as royalty and agents alike are removed. The list is too long to mention everybody, but it bears pointing out that the entire spectrum of political activity is represented.

Sometimes the violence is revolutionary. There’s Vera Figner and Nicholas Kibalchich, the assassins of Emperor Alexander II, himself best known for liberating Russia’s serfs. Leon Czolgosz, who inflicted the killing gunshot on President William McKinley. Sergei Kravchinsky, who slashed the head of Russia’s Gendarme corps to death in the streets.

Other times the violence is institutional, as with Wilhelm Stieber, inventor of the modern surveillance state; Peter Rachkovsky and his Okhrana; Baron Ungern-Sternberg, with his taste for massacring Bolsheviks in Mongolia.

And sometimes it’s cultural, refusing to sidestep even Matvei Golovinski, the probable author of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the infamous anti-Semitic document that “exposed” a Jewish plot to dominate the world. The Black Hand, the organization that assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand and precipitated the First World War, doubles the victory points earned for assassinating royalty — arguably a thematic misstep, since it’s the game’s loyalists who hope to usher in a devastating worldwide conflict. Amusingly, there’s an entire class of embittered intellectuals, consisting of figures such as Emma Goldman and Prince Kropotkin, who are more interested in promulgating ideas than throwing bombs. These agents are worth victory points to the restorationists while offering little tangible help when it comes to purging the Earth of its overlords from the depths of outer space.

If that last line snaps us from our historical reverie, the effect is intentional. Greenwashing serves a perpendicular function to whitewashing, easing the impact of the situation by dressing its antagonists in the board game equivalent of rubber masks. Transformed into existential threats to our species, these oppressive royals demand no empathy when blown apart. This suspends a gauze of fiction between the game’s players and the historical actions they’re asked to undertake. In his design notes, Wallace notes, “I had this feeling that some players might object to a game where your main occupation would be going around blowing up various world leaders.” The solution was Neil Gaiman’s short story, which served as a serendipitous means of fictionalizing history. For anyone who might balk at the idea of chucking a bomb at a Windsor, A Study in Emerald ensures that your target isn’t Queen Elizabeth II’s grandfather. It’s an Old One whose principal diet is babies. Unless, of course, your loyalties skew the other way. In which case, here’s your morning basket of babies, m’lord.

We’ll discuss the implications of this greenwashing momentarily. First, though, let’s take a look at Wallace’s sequel to A Study in Emerald, AuZtralia.

According to AuZtralia, the good guys won. The occupation that had begun in 1180 was at last thrown off in 1888 when the Old Ones disappeared from their palaces and fortresses. Of course, our extraterrestrial dictators had spent their seven centuries of preeminence working to extract resources from the known world, leaving entire swaths of the world charred and infertile.

The only solution was expansion. Embarking on great voyages of exploration, humanity eventually discovered an untouched continent. It was soon named Terra Australis, “the South Land” in Latin, after the work of the 5th-century writer Macrobius, who had posited that the continents of the Earth must be balanced in contrasting antipodean proportions. Early expeditions were encouraging: this was virgin territory, untouched by the ravishments of the Old Ones. Between fertile lowlands, grazing hills, and rich deposits of coal, iron, and gold, Australia seemed like it could be the answer to the slow starvation of humanity. This marks the beginning of the game. Players are given command of colonies on the coast, with orders to build rails to reach the continent’s interior, harvest deposits of resources, and establish life-saving farms.

Before we even consider the game’s greenwashing, it’s important to note how Wallace has already cast the history of colonization in a new light. Written in 1899, only a short eleven years after humanity’s fictional victory in A Study in Emerald, Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden” provides an instructional glimpse into the attitudes of imperialists in the late 19th century. It’s tempting to examine the entire thing through the lens of today’s topic, and I would encourage everybody to push through it all, but for now we’ll confine ourselves to its opening stanza.

Take up the White Man’s burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

Some have argued that Kipling’s tone is satirical. While there’s an argument to be made along those lines, the context surrounding “The White Man’s Burden” doesn’t do it any favors. Its full title includes the subscript “The United States and the Philippine Islands.” Written during the Spanish-American War, its meaning was understood both by supporters and detractors of imperialism as urging the United States to take up the cause of annexing the Philippines. The barrage of parodies was immediate. English politician Henry Labouchère, an outspoken critic of imperial policies, responded:

Pile on the brown man’s burden

To gratify your greed;

Go, clear away the “niggers”

Who progress would impede:

Be very stern, for truly

’Tis useless to be mild

With new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

(To muddy any newfound affection for Labouchère, he’s better known for his 1885 amendment criminalizing homosexuality. Remember, history is complicated — and rarely comfortable.)

Kipling’s thesis expands the remit of colonialism. Rather than solely serving its parent country, colonialism is cast as a benevolent force embarked upon a mission of civilization not unlike the role of a parent, meant to uplift the subjects of its occupation. Forced exports, taxation, corruption, wars of subjugation — these are unfortunate but inevitable side effects, not the principal functions of imperialism. As a later couplet puts it, the White Man’s reward for shouldering his burden is “The blame of those ye better, / The hate of those ye guard.” Contrary to accusations of presentism, such blunt paternalism was criticized even in its day. Mark Twain was disappointed when the United States colonized the Philippines. In his anti-imperial essay “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” he bitterly proposed that the flag for the Philippine Province could be “just our usual flag, with the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and cross-bones.” The notion of noble blood parenting over uncivilized blood may have been more widely accepted, but many regarded it as a travesty.

What makes AuZtralia so interesting is that Wallace rewrites all of that. First, he provides an absolute justification for colonialism rather than a flimsy excuse. Humanity’s lean times are the result of alien occupation. Most land has been left nonarable. There’s no reason to rationalize a European incursion by mythologizing the White Man’s Burden, because failure to settle the southern continent will spell disaster for millions. Furthermore, there’s no need to fret over the fate of the indigenous population; they were presumably already removed by the Old Ones, who have transformed the continent into their final holdout against the human uprising.

This is the second step of AuZtralia’s gameplay and internal fiction. As players expand inland, they risk stirring the slumbering Old Ones. These take a few forms: zombie hordes that are slow but plentiful, loyalist humans, ancient temples that fray the mind, swooping mi-gos and lurking shoggoths. It isn’t long before the Old Ones begin awakening in earnest, acting as an additional faction that burns farms and tries to drive the humans back into the sea.

And it’s hard not to regard them as stand-ins for indigenous Australians.

III. The History Wars & Greenwashing

History is a war. In some cases it’s such a war that there’s nothing else to call it.

You may have heard of Australia’s History Wars. In 1968, Australian anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner gave a lecture entitled “After the Dreaming,” in which he coined the phrase “the great Australian silence.” The topic was the erasure of Aboriginal peoples from Australian consciousness. As Stanner argued, “It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned under habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness practiced on a national scale. We have been able for so long to disremember the Aborigines that we are now hard put to keep them in mind even when we most want to do so… They typify so vividly the other side of a story over which the great Australian silence reigns; the story of the things we were unconsciously resolved not to discuss with them or treat with them about; the story, in short, of the unacknowledged relations between two racial groups within a single field of life supposedly unified by the principle of assimilation.”

Over the following decades, Stanner had his wish granted, although probably not in the manner he would have preferred. The debate over Australia’s national history reached as high as its prime ministers, with both Paul Keating (Labor Party, PM from 1991-1996) and John Howard (Liberal Party, PM from 1996-2007) beating the drum, amounting to nothing less than a struggle to define the country’s national character. This debate was characterized by two pejorative symbols. The label “black armband” was applied to those who argued that Australian history had been purged of its atrocities. According to their detractors, such arguments were exaggerated, cynical, and determined to overshadow the accomplishments of early settlers. In response, the black armbands labeled their opponents “white blindfolds,” determined to turn away from even the possibility of atrocity rather than face it head-on.

The History Wars are ongoing. Some deny that certain massacres took place at all, despite the existence of contemporary reports to the contrary. Still, public opinion seems to be bending, in part thanks to the Bringing Them Home report. The product of a national inquiry, Bringing Them Home confirmed that Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children had been forcibly removed from their families by government agencies and church missions. The issue, once again, was blood. On the assumption that full-blood Aboriginals were doomed to extinction, children of mixed descent were prioritized for placement in missions and reservations between 1910 and 1970. Some argued that their Aboriginal blood and darker skin would eventually be bred out, resulting in productive white-skinned adults two or three generations hence. The current estimate stands at northward of 100,000 children taken. Even after a federal apology in 2008 by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, many of the report’s recommendations have yet to be taken.

Erasure. In Australia’s case, erasure with twin meanings: first a people’s place in history; eventually, their very selfhood. The game fares better, but only just: of thirty-three personality cards, only two feature characters who are unambiguously Aboriginal.

Both A Study in Emerald and AuZtralia greenwash their subject matter. As I mentioned before, greenwashing is a process that takes human figures and transforms them into something alien. It is the very definition of othering. There are advantages and pitfalls to such a process. Martin Wallace’s titles illustrate both.

There’s a moment in Chesterton’s The Man Who Would Be Thursday when the heroes approach Sunday, the leader of the anarchist movement, to ask why they — “they” being protagonist Gabriel Syme and his fellow policemen — were made to go undercover as bomb-throwing anarchists and set against one another. The scene parallels the conclusion to the Book of Job, when God at last delivers a response to the title character’s agony (or rather, refuses to give a response). The answer in Thursday acts as Chesterton’s theodicy, a response to the question of human suffering. In a spasm of insight, Syme realizes that everything in the world, himself included, was made to wage war against everything else “So that each man fighting for order may be as brave and good a man as the dynamiter.” In this formulation, all of humanity suffers alike, good people and bad, in order to expose the best in the worst and the worst in the best.

That theodicy might also act as a mission statement for A Study in Emerald. Why are the royalty of Europe portrayed as monsters? So that you, the player, can experience the bravery, zeal, and isolation felt by the 19th-century radicals who wrote treatises against absolute monarchy, agitated for constitutions and concessions despite the danger posed to their bodies and property, and even lit fuses to annihilate the bodies of their rulers. Or, inversely, so that you can experience the horror of propagating a monstrous system. The object of the game’s greenwashing poses little danger to history; the personhood of European royalty isn’t in doubt, either then or now. But it presents a tremendous opportunity, taking the darker hues of political extremism and inverting them. What was previously “bad” is now permissible, even righteous. With some investigation, it becomes possible to see how anti-monarchism, socialism, and anarchist movements were dimensions of a complicated situation that shepherded Europe away from absolute rule and toward a more egalitarian and democratic society.

It helps that this is an inversion across the board. The blood being rendered ichorous is not the stuff typically considered savage — it’s the noble blood. If anything, A Study in Emerald expands the divine right of kings to its extreme conclusion. There’s no question that the Old Ones are suited to rule; by their very nature, they are more powerful and more intelligent than their human subjects. Their blood is made of sterner stuff, tracing beyond legend, bestowing powers that mustn’t be comingled with the human race. The question, then, isn’t one of suitability. It’s one of right. Of self-determination. The rulers of Europe should be cast down not because they aren’t capable of rule, but because it’s wrong for one entity, no matter how potent, to hold sway over countless others. At its core, A Study in Emerald is viciously democratic.

Of course, it might be possible to draw a similar thread through AuZtralia. By repurposing the indigenous population into aliens, doesn’t it also turn something “bad” into something permissible?

In one sense, yes. In another, AuZtralia’s argument is pedestrian.

At the heart of Australian colonialism is the concept of terra nullius— literally, “nobody’s land.” By coming into possession of an uninhabited continent, the English had lucked into a windfall: a land ripe for settlement, with none of the problems that attended their efforts elsewhere. This narrative relied on the non-personhood of the continent’s indigenous inhabitants. One of the sponsors of Lieutenant (later Captain) James Cook’s voyage stipulated that any local indigenous people were, “in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit. No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or settle among them without their voluntary consent.”

This statement went unheeded. Colonial efforts in Australia rested on the assumption that Aboriginal people were not, in fact, people. The entire continent could be claimed because it was terra nullius. It belonged to nobody. Because non-persons cannot have borders, property, or individual rights, nothing stood between Australia’s colonists and the displacement, massacre, and kidnapping of its inhabitants. As always, the reality is more complicated than a single statement can account for. Governor Sir George Arthur made a proclamation that both whites and Aboriginals were to coexist peacefully. Illustrative panels were furnished to depict both races being hanged as punishment for killing the other. Even so, this proclamation was often used as pretext for removing or attacking indigenous enclaves. The violence was widespread and often decentralized. In the latter case, because colonists were more able to call upon the government’s intervention when attacked, there was often no recourse for an offended Aboriginal. Arthur’s proclamation may have been well-intentioned, but it overwhelmingly benefited white settlers.

One friend has jokingly suggested that the antagonists of AuZtralia might be upscaled versions of the migrating emus that pillaged Western Australia in the 1930s. Dubbed the “Great Emu War,” this peculiarity of Australian history saw twenty thousand emus rampaging through the farmlands of WWI veterans. The farmers eventually called upon the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery, a force that numbered three soldiers and two machine guns. Accounts of the “war” are humorous, even slapstick, complete with inclement weather, jamming weaponry, and an early victory for the emus. The Major compared his foe to the Zulus of Southern Africa, and it’s telling that this incident became fodder for Australian national myth, while conflicts with its Aboriginal population were collectively forgotten. Better to recall defeat at the hands of flightless birds than victory against outnumbered and outgunned natives.

This is why AuZtralia’s greenwashing strikes such a different tone from that of A Study in Emerald. Historical erasure and xenophobia are replaced by xenophobia of a different stripe, one that’s acceptable because the aliens you’re stamping out are actual aliens. This is nothing new, either for Australia’s history, which alienated and erased its Aboriginal population, or for the work of H.P. Lovecraft, with its fear of pure blood breeding with corruption and degeneracy. These bedfellows make a distressing but unsurprising couple, inadvertently promulgating a wide range of ideas that are unfortunately still under discussion in the History Wars: the emptiness of Terra Australis, the non-personhood of its inhabitants, and the factuality and extent of massacres, kidnapping, and other injustices. It’s also hard to escape noticing that A Study in Emerald permits its players to advocate for the Old Ones — effectively, to stand in favor of greenwashed monarchism. Meanwhile, although a recent Kickstarter campaign has proposed an expansion to let somebody play the role of AuZtralia’s antagonists, as of yet no parallel dignity is paid to its greenwashed Aboriginals. Like the generations of Aboriginal peoples Stanner lectured about in 1968, they are silent.

To be clear, none of this is to speak to Wallace’s character or the intentions behind either of these games. Both greenwash history to cushion the roles and actions they ask of their players. A Study in Emerald uses greenwashing to remediate the omissions, misconceptions, and stereotypes of popular history — in effect, to shine a light into overlooked corners. By contrast, AuZtralia’s greenwashing reinforces omissions and misconceptions. No long-neglected corners are dusted.

This difference — between remediation and reinforcement, between inversion and the status quo — can sometimes appear slender, but it’s important to consider. Board games about history have often suffered a collective forgetfulness of their own, leaning closer to comfort than introspection, and leaving chalk outlines where once stood the recipients of colonial abuses. To Wallace’s credit, his duology experiments with an alternative brand of inclusion, one that allows him to define the parameters of the roles he bestows upon his players. By casting his foes as alien invaders, he commands a firm grip on issues that would otherwise be too morally fraught to consider in a commercial product. As you can see, the results speak to the difficulty of using greenwashing as a technique.

That said, even if the results are mixed in AuZtralia’s case, it succeeds at placing its players within reach of the colonizer’s mindset. Ravenous for natural resources, bent on expanding at all costs, yet terrified of the other, its players are spurred to violence at the slightest provocation. Here, those acts of violence are justified only because of the game’s greenwashing. Still, that mindset is achieved. Whether such an accomplishment is valuable when there’s no shortage of games about colonialism from the perspective of the colonizer, I’ll leave up to you.

History, after all, is a war. Whether we’re discussing pioneer mythology, political radicalism, or indigenous erasure, it’s worthwhile examining the role our games play in either entrenching comfortable narratives or splitting them open to reveal the complexities, self-examination, and richness within.

Many thanks to Eryck Tait for this essay’s header image, and to the many readers who were willing to suffer through early drafts.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

Posted on August 12, 2021, in Board Game and tagged A Study in Emerald, AuZtralia, Martin Wallace, Talking About Games. Bookmark the permalink. 39 Comments.

I almost missed my stop on the subway due to reading so deeply. Thank you for this feast for thought!

Thanks for reading, Brian.

“it’s telling that this incident became fodder for Australian national myth, while conflicts with its Aboriginal population were collectively forgotten”

I’m Australian and have literally never heard another Australian mention “the Emu War”, Americans really seem to love talking about it though.

Haha, so it goes.

For what it’s worth, the two Australians who were kind enough to read an early draft had both been taught about the Emu War in school. And I’d never heard of the thing until a friend brought it up while discussing the possibility of this article over a play of AuZtralia!

Hey! We are here for games, amusement. You have no business being erudite, enlightened, insightful, reflected, frightfully intelligent and a superior stylist, be careful or people might learn something.

You’re right… this article should have been the letters F U N blinking in your eyeballs!

I love this essay; thank you for it.

It’s such a shame though that “greenwashing” already has a reasonably well-known meaning separate from the one you gave it here: a PR effort emphasising environmental friendliness in order to cover up damaging activities. From the title I thought you were going to be writing about another current boardgaming issue entirely.

Guess what I learned when I was already halfway done with this piece? Yep. You guessed it.

I just shrugged. “Emeraldwashing” sounded too much like a process for blinging out a pair of Jeans.

May I suggest “xenowashing”? To make something an extreme outsider. It’s not quite as catchy, but avoids the conflict of terminology…

Sure, that works.

Thanks for a very interesting read. I grew up in Africa, but migrated to America and have settled in Utah, so your comments on Mormons and Colonialism strike home for me. History is messy and complicated, just like the world we inhabit today.

I’m glad to have you here! There are so many things I love about Utah. Plenty I don’t as well. But it’s a beautiful place and worth the fighting for.

Thanks, Dan, for such a thought-provoking piece.

A lot of reviews and other boardgame articles in the blogs I read, I kind of skim a little bit.

This one I read word for word. That’s how powerful it was.

Glad you found it worthwhile, Dave, and thank you for reading!

Another amazing text. Thank you so much for this. A lot of food for thought.

Thanks for feasting with me, pedorido!

Lots to chew on here; I live in Canada where we are currently undergoing our own, unfortunately politicized, history-war over the role of colonialism, especially as it takes shape in legacy of residential schools. Lots of strong feelings; lots of misunderstandings; lots more important conversations to have. I appreciate your deeply compassionate, unflinching look into these difficult, hard to discuss, topics.

While it is not the main argument of your piece, I will, if you’ll allow me, take issue with your dismissal of concerns re: Critical Race Theory. I happen to have a much more charitable view of the crying parents who, if you listen carefully, often have legitimate concerns about the inclusion of highly divisive, controversial academic theories in their children’s classrooms. And it IS in classrooms, I’m afraid: my degree in Education from last year was almost entirely awash with the stuff, it is mandated professional development, and is lived out among my colleagues.

Now, before we talk past each-other, you point out that a definition of CRT is hard to come by so maybe I should define mine. I think the charitable interpretation is something like the following: an attempt to understand the role of racism (and discrimination on the basis of identity more broadly) in systems and power structures, both historically and today. I can get behind this. The problem is when, as it frequently does, CRT oversteps its bounds, mutating into a “theory of everything” that sees racism or power imbalance as THE universal impetus behind all social inequality. Here, it begins to borrow from Marxism, intersectionalism, and social justice movements to concoct a totalizing worldview that encourages it’s adherents to see people primarily as archetypes of their identity groups, playing out a kind of Manichean pageant of evil oppressors vs. enlightened victims. I think this is really dangerous, very tribalistic stuff that results in lopsided, myopic readings of history of exactly the kind you rail against above.

Now, I don’t think any of this is necessarily more dangerous or prevalent than the whitewashing, nationalistic, bull-sh*t that CRT purports to fight against; I also think the recent attempts to ban CRT in classrooms are dangerous and unconstitutional. I just wouldn’t so quickly dismiss concerns about CRT as relegated to uneducated, emotional parents or as a small, ivory-tower theory found only in law schools (even if it that was it’s origin). Very thoughtful, compassionate people take issue with it: I’m influenced primarily by the likes of John McWhorter, Glenn Loury, Chloe Valdary, Andrew Sullivan, and many others who would be hard to dismiss as merely conservative talking-heads.

What do you think, Dan? Am I missing anything here? What have your encounters with CRT been like? Thanks again for the invigorating piece!

Great questions, Caleb, even if, as you’ve noted, that isn’t really the subject at hand. Unfortunately, any response would require an entirely different essay, so I’ll have to leave you with that most useless of statements, the personal anecdote.

We received a panicked text from a relative begging us to stop “critical race theory” from being taught in our local elementary school. My relative’s daughter had been taught that because of her whiteness, she was to blame for historic ills — a decidedly unfortunate (if poetic) inversion of her religious upbringing, which taught that the darkness of Native American skin was proof of their hereditary sinfulness, although of course this particular irony went somehow unnoted. This youngster was soon asked to have her account be included as part of a plea to the school board.

Only problem is, my own daughter was in the very same class. So was my aunt, who volunteers as an aide. So were the children of a number of friends. In accordance with Brandolini’s Law, it took quite a bit more time and effort for the real story to stitch itself together. The entire account had been a fabrication, formulated in response to then-President Trump’s denunciation of CRT and inauguration of state-sponsored “patriotic education.”

Over the entire course of completing my PhD, I never once heard the phrase “critical race theory.” Turns out, that’s because CRT isn’t something I would have learned as a historian; it’s a legal heuristic, and an old one at that, and in the United States has become a catchall term for any examination of systemic racism. Seeking to ban any discussion has become the latest flavor of McCarthyism. Like McCarthyism, it sees opponents everywhere, imagines that an enormous range of theories and theorists are instead a monolithic conspiracy, and lays blame opportunistically, assembling into an easy weapon that can target anyone and can mean anything, which makes it impossible to defend against. It’s true enough that CRT, like Communism, exists somewhere. But every single account of “CRT being taught in schools” that I’ve heard has not been an accurate statement.

If we’re instead talking about “systemic racism being taught in schools,” then we can take heart, because there is no central orthodoxy, no consensus, no conspiracy. I have no doubt that plenty of educators have done a terrible job of talking about systemic racism, in exactly the same way that I know firsthand of educators who taught their own personal theologies and bigotries in science and history classrooms during my own time as a student.

In place of such a conspiracy, the educators I’m aware of who are discussing systemic racism are engaged in a vibrant and ongoing discussion over how to best discuss such topics — which is exactly what we should want from our educators.

Dammit. I wrote an essay. My deepest apologies.

An essay is exactly what I was looking for! Thanks for taking the time to respond. In the end, anecdotes are probably what fuel a lot of our rationalization after the fact, so I appreciate you sharing yours insofar as it allows me to better understand where you’re coming from. And to be honest, my experience of a very shallow, resentful attempt to discuss race in my education program has probably left me more cynical towards good-faith attempts of racial reconicialtion than is necessary.

I also agree that CRT as a conspiratorial bogeyman is definitely a problem, serving much the same purpose I think accusations of “racism” can for those wishing to smear their political opponents or grab power. Good to be sceptical of totalizing claims from either side (I say even as I recognize that “sides” both “left” and “right” are becoming increasingly unhelpful categories to describe our current moment).

In the end, I guess I would just argue that a word or phrase is as much its dictionary definition as it is its definition in common parlance. For many, “racism” no longer just means “a belief that race is a fundamental determinant of human traits and capacities” as Merriam-Webster would have it; instead, it describes something like “entrenched systems of power that privilege so-called ‘whiteness'”. I could choose to hold to my dictionary definition and dismiss claims of this new kind of “racism” as unfounded, but I would be ignoring a lot of important insights to my own detriment and that of the conversation.

I think the same might be said about “CRT”. Sure, one could point to the narrow, legal, mostly academic origins of the theory as you do. But for many, including myself, it is a helpful catch-all (even as “catch-alls” can be dangerous as you say) for an increasingly growing movement of religious fervor that seeks to expunge racism (read: “original sin”) largely through public, symbolic confessions of culpability (read: “penance”) that bring us closer to a day of “racial reckoning” (“the end times”). One just has to be careful to not say anything politically incorrect (“heresy”) at the risk of being cancelled (“excommunicated”). Most importantly, I will note the lack of forgiveness and charity towards others inherent in this otherwise religious project. Much of this is obviously antithetical to the liberal project and rational, open inquiry into the complex matters of inequality and racism.

Okay, okay, I’m probably being a bit melodramatic and turning you off from my argument, so I’ll stop. I also know that most of those who are concerned, rightly, about the legacy of racism today, are thoughtful, compassionate folks who do not so easily fall into the tropes I laid out above. Let it suffice to say, though, that I think, for many, being part of a growing movement against racism and landing on the right side of history fills Pascal’s “God-shaped hole” in their hearts. Especially as a Christian, I think this is kind of stand-in for genuine faith is dangerous and a very real phenomenon that, for better or worse, CRT has come describe.

More to the point, I also believe this new “woke religion” (if you’ll allow me such a crude term, as I grasp to describe an emerging situation) has an intellectual lineage the can be traced back to the narrow, law school origins of CRT you mention. At the very least, I know of people smarter than myself (see my previous post) who have done this work.

In sum: I hope and trust you are willing to meet people concerned about CRT on their own terms, as they may be seeing a very real threat, even as they use slippery buzzwords to describe it.

Thanks again for hearing me out. Here’s hoping my comment gets through your pesky spam filters! If not, I will be sure to raise a fuss about the hegemonic powers of social media that seek to silence my right to free speech 😉

Well my mission president once told me a story isn’t worth telling of it isn’t worth exaggerating…

… wowza.

Interesting, I never made a connection between MWWT and Job. Even hearing it, I don’t think I see it. Will have to think about this more. But just as a point of order, the book’s subtitle is “A Nightmare”, and Chesterton is emphatic that this is crucial to understanding the book. The ending is most definitely NOT Chesterton’s theodicy. Maybe you mean that it’s the BOOK’S theodicy, which Chesterton himself disapproves of and is trying to satirize? If so I may have misunderstood you and apologize!

You are incorrect. Chesterton uses The Man Who Was Thursday to construct a theodicy for the problem of natural evil (as opposed to his favored free-will defense of the problem of moral evil), in which God’s playfulness lends insight through the depths of creation’s mystery and even absurdity. In Thursday, that theodicy is given its fullest expression when the complaints of the Adversary are un-justified by the chaos faced by Syme and his companions, who have seen through similar complaints to their final, joyous conclusion.

Dan, I think this is some of your most thoughtful written work to grace these pages. My interest in your analysis was piqued when you referenced Kipling’s poem, because I’m married to a Filipina and we’ve always taught our mixed children about the difficult nature of colonial history and its inevitable distortion by cultural experience.

The United States conducted a brutal counter-insurgency campaign during our colonization of the Philippine islands at the turn of the century, and yet many Filipinos have adopted the familiar and heroic WW2 narrative of Douglas MacArthur’s “I Shall Return” liberation from the even greater atrocities of the Japanese occupation. In the post-war period, the United States enabled Ferdinand Marcos’ oppression and corruption because of his anti-communist stance, until Ronald Reagan withdrew his support and compelled Marcos to flee to Hawaii at the height of the People’s Power Revolution in 1986. Even though Reagan had continued the dictator-friendly policies of prior presidential administrations, he was held in high esteem by many Filipinos for his assistance in removing Marcos.

Although my wife acknowledges the violence of American colonialism, she strongly subscribes to the MacArthur/Reagan liberation mythos. Through the years, we’ve paid our respects at Pearl Harbor and Corregidor, and strolled hand in hand along the EDSA in Metro Manila, where the power of the people displaced Marcos and restored democracy in the Philippines.

“History is complicated- and rarely comfortable” is a familiar mantra in our household.

Thank you for sharing, TM! I truly appreciate your perspective. One of the reasons I’m so fascinated by history is because of how events ripple forward in time to affect our lives in tangible ways.

So, Dan, what are the games that present a more balanced view of colonialism? I’ve played King Philips War, a light wargame that places indigenous people in one of the two sides of the battle and they have a fair shot at winning the war (and a reflection of 1690s New England as well.).

But I don’t if it’s checking the correct box merely by empowering the indigenous side. There’s no greenwashing here, so it’s not precisely similar to your essay’s case. My concern is that representing “colonialism” in a fairer light is as much about presentation as anything. “KPW” does indeed present Metacomet and the Wampanoags in a respectful light, and this isn’t just a game about smashing heads. There’s political aspects, especially on the natives’ side of the table. They’re not presented just as pieces to destroy. That said, it’s a conflict game, not a colonization game.

So Wallace’s efforts kind of said, “ok, we can represent colonialism as long as we add tentacles” and that’s clearly pretty bogus. But if a designer wants to go after the engine-building, explore-expand part of the gaming oeuvres, is there any way at all to give it an historical setting? Or is the setting too deeply tied to the sin? Are tentacles the best we can do?

I think there are plenty of ways to do it! Greenwashing — or as one person brilliantly put it in response to this piece, “graywashing” — is only one. I like Endeavor quite a bit for this reason.

Thank you for another thought provoking article, worthy of more than just one read.

I’d be keen to hear your thoughts on the same subject, but in relation to the works of Tolkien.

It may be that the high regard in which his works are held make shaking that particular pedestal a more potentially explosive affair, but I’ve heard more than one accusation of racism levelled at him, and The Lord of the Rings, in particular.

Whilst they aren’t exactly aliens, orcs and half-orcs are also figments of imagination (at this time, in relation to aliens) and the thorny issue of ‘lesser’ races of evil creatures, especially mixed races, could easily be construed as such.

It’s worthy of a separate essay, but is very close to this one. I’d be very interested to read your views, if you have the inclination.

There was a great piece on Tolkien and Orientalism a while back. Basically, it argued that the orcs weren’t Germans, as many people reflexively argue, but Asians, right down to their physical descriptions. The Yellow Peril come to Middle Earth, so to speak.

I can’t seem to find it now. Rather, I seem to finding so much writing on the topic that I can’t figure out which one was the piece I read.

It was by James Mendez Hodes, if that helps steer your Google-inator in the right direction. It was based on a line in a letter Tolkien wrote, and extrapolates from that to infer that the point of Lord of the Rings is the triumph of European types and the defeat of villainous Asians.

Thanks, great article. I think your description of history being a war of smashing models applies equally to current events.

Excellent read thanks for writing.

Pingback: Colonizers vs. Pirates vs. Egyptians! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Embrace the randomness! – Fluffy`s Board Game Shelf Evolution

Pingback: Ludology 261 – Tinner’s Tips and Tricks - Hot News about board games right now for you

Pingback: Gastbeitrag;: How to irritate people – H.P. Lovecraft und die Brettspielszene – spielbar.com

Pingback: Ludology: Ludology 261 – Tinner’s Tips and Tricks Game Download – NINEJAGIDI.COM

Pingback: Ludology: Ludology 261 - Tinner's Tips and Tricks - Mad City Games

Pingback: The Shoggoth and the Shotgun | SPACE-BIFF!