More Than Merely a Civilization Game

When I complain about civgames, my harping comes from a place of deep affection. It’s just that civgames tend to be very good at one model of how civilizations flourish, and very bad at every other model. If it isn’t steady border expansion and technological growth, with very little diversity or ideological synthesis, it doesn’t usually rate. Because really, how many civilizations have spanned from remote BCE to far CE without redefining who they are? Without changing languages, dynasties, ethics, goals? I’ll give you a clue: not many. Even fewer were captained by Sid Meier’s immortal and nuke-happy Gandhi.

Enter Phil Eklund and Jon Manker’s Bios: Origins. As the third in the Bios trilogy, set after the multi-cellular life of Genesis and the prehistoric beasts of Megafauna, Origins is a civgame right down to certain familiar trappings. Tech tracks, cities, and special resources are all present and accounted for. But these trappings are only part of the story. What makes Origins special is the way it answers the questions that other civgames don’t even begin to think about. Questions like who you are — you, the player — what you want, and how very different peoples and civilizations can prosper across the ages.

To describe what I mean, let’s slowly zoom in from globe level. First you see the continents framed by water, vegetation and mountains and sand almost dull against that lapis lazuli backdrop. Then the sphere rotates into near-total darkness. Closer, there are pinpricks of light. Not the modern planet, then, but far enough along in human development that there are hubs of activity, places where torches and lamps burn and smoke through the night. Closer, two civilizations, grown into and around each other like interlaced fingers, are locked in conflict. Cities are traded. Some are destroyed. Refugees flee, settling nearby or far away. Those cities, too, trade hands back and forth.

This is a conflict. But as we move even closer, it’s very much unlike the conflicts presented by other titles. Rather than being a mere struggle for the usual candidates, resources or land or, heaven forbid, victory points, this is an ideological struggle. This is a clash between two very different beliefs. And one of them isn’t so much a belief as an economic model.

The first ideology is, however, a belief. A very strong belief, bolstered by a centuries-old priestly class. These aged men — that they’re men is a safe guess, as is the guess that they’re gray-haired and heavily wrinkled — are the power behind the throne. And their preferred method of warmaking is appropriately underhanded. Rather than surrounding a city, starving it into submission, and burning everything and everyone within, they send preachers. Holy men. Prophets. These missionaries take root like worms in fruit. Add a few decades of mere talking, the city is now theirs.

If that sounds pernicious, wait until you get a load of their opposition. The rival empire isn’t so patient. They don’t intend to wait around for people to change their minds. There’s no time for blabbering about the soul and the cloud-fellow when there’s work to be done. Which is why their method is more blunt: slavery. They walk in, herd everyone into their fields and their brick-drying camps, and after a while it’s only natural that the depleted city will strike a bargain.

What’s striking about this story can be broken into three details. First, both of these civilizations are in a tight spot. The former depends on the superiority of its priestly class, and is desperately trying to nurture enough of an urban population to put a stop to its rival’s predation; its rival, meanwhile, would love to hire some priests to explain why its citizens shouldn’t worry so much about their eternal souls. It’s an arms race, but waged along two non-parallel tracks, and neither seems able to catch up to the other. Instead, they’re trapped in place, like a dance with complicated footwork that takes its partners nowhere. Second, these civilizations didn’t sprout from the ground fully-formed, but developed their ideas and strengths over a very long time, growing more powerful and more entrenched. And third, this is one story in a string of stories, from cave paintings to mythologized epics to meticulous history, all in a single sitting.

Oh, and that story is about to bend out of necessity. Because the religious state has been working overtime to promote a concept that might seem counterintuitive: that every soul is free, beholden to no man, capable of determining their own course. As this idea takes root in humanity at large, their more industrious rival is going to feel some pushback on that whole enslavement thing. Enough pushback that it will shatter the core principles of their civilization. What emerges from that reshaping might be tame or terror.

Sound complicated? It is, to a degree. Like many of Eklund’s designs, Origins is a cyclone of icons and terms, terms and icons. What’s the difference between domesticating a reindeer and a camel? Between a quiet and a chaotic revolution? Between migrating through the jungle and through the desert? Between suffering chaos and quelling chaos? Between a city being destroyed by a rival army or the Yellowstone eruption? Taken on their own, none of these concepts kick up any fuss. They’re like being stuck with a pin, a moment’s sting and they’re done. It’s only when blended together that everything swirls into a mess. War animals like camels let you ignore the blitzkrieg rule, quiet revolutions let you change your ruling class more flexibly, jungles and deserts require different technologies, quelling chaos means killing an elder or destroying a city to get rid of dissidents, and Yellowstone doesn’t cause chaos because it was an “Act of God,” the game’s way of saying not your fault. Hope you were listening. This will be on the test.

Of course, this is to be expected of a game that hopes to simulate something more involved than the usual civgame model. This isn’t extraneous verbiage. It’s exactly enough to portray city-states that can compete against expansive empires, religions that struggle against science, even bronze-using navigators that somehow circumnavigate the globe. With so much going on under the hood, the surprising thing is how Eklund and Manker have compacted all those concepts into a streamlined system. It’s reminiscent of a jumbo jet. Just because it’s heavy doesn’t mean all those pieces don’t fit together just so.

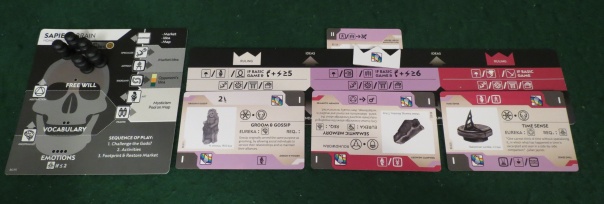

To that end, nearly everything important in Origins revolves around two decks: foundations and ideas. The manner of their acquisition is different, but their commonality is that they’re always oriented in one of two ways, slotting into columns representing the game’s three-way emphasis on culture, politics, and industry. Domesticating dogs, for example, unlocks a cultural idea in which your good doggies help you domesticate other animals. Or that same card can be rotated for its political advantage — enslavement. Bad doggies.

The caveat is that your civilization can only inhabit a single column at once. These aren’t so narrow that you’ll be shoehorned into a single approach for sticking with industry over politics, but there are tendencies to observe, like culture favoring religion or industry eventually birthing science. The trick is that while foundation cards stick around pretty much forever, ideas disappear whenever you hit a certain limit, research an obsoleting idea, or switch from one column to the other.

This last detail is crucial, rewarding players for specializing until the moment they’re forced to switch to another government. One time, my people were enthusiastic industrialists, with a huge stack of foundations and ideas. A big stack generally translates to a big turn, since you start at the bottom foundation card and work your way up to the most recent idea, triggering one icon from each. This meant I was merrily founding two or three cities per turn. My competition looked on in envy, unable to keep up with such maddening disregard for anything but the fires of industry.

But even the hardest iron can be made to rust. It started out slow. Pollution hit when my cities outnumbered my ability to generate energy. A war on my borders left a fledgling city smoldering. Because my cards were plentiful, there was no need to placate the dissidents spilling into my tableau. Sure, they were blocking some abilities with their demonstrations. But when your civilization has more factories where that closed-down one came from, what’s the harm in leaving some portion of your population unhappy?

You’d think I never learned any history. Another player challenged the gods, the game’s nomenclature for risking a draw from the event deck. These spark all sorts of terrible incidents, including sweeping climate change that can leave Southeast Asia underwater or the equator choked in jungles. They also, after being auctioned, become foundations.

The Labor Unions card is an exception. Instead of being auctioned, Labor Unions are immediately given to the player with the most dissent. Which, if you’ve been paying attention, was my hyper-industrialist utopia. Not only was I forced to change governments, but these upstart workers overthrew the remnants of what I’d had in that column before, one of the very few ways that foundation cards can be removed from the game. Some of my ideas were flexible enough to come along, rotating from industrial red to cultural white, but most were discarded. In the span of a single short revolution, I’d gone from the most potent empire in human history to a backward theocracy that had never developed any actual theology.

It helps that such moments are framed with uncommon care. Instead of donning the robes of most civgames’ immortal leader — or the lingering question mark of a designer who didn’t feel the issue was worth considering — Origins casts your people as its protagonists. Early on you’re a subspecies, then a language, then a religion, and lastly an ideology. Rather than being handy tags, these inform the governing decisions of each epoch. Those first turns are about wandering nomads and the development of your brain. Later, cities sprout around whichever resources you’ve learned to cultivate, domesticate, or mine. This eventually ignites conflicts over living space and spoils. By the end, despots and runaway ideas, like those Labor Unions, pose as much threat as external factors. It’s a long tale, the very definition of an epic, yet it’s consistent in the telling despite shifting perspectives and values and goals.

Speaking of goals, it’s possible that nothing is more reflective of what Origins is striving toward than its three victory conditions. Rather than tallying up a single score, each epoch sees its civilizations chasing a shared, but changing, objective. The first epoch is all about forming a religion; whoever has the most priests earns a VP token for every player with fewer priests. The second epoch is similar but with cities, generally seeing a boom of construction and takeover. And lastly, you’re judged on your civilization’s diversity, earned only through foundation cards.

The brilliant part, however, is that you can entirely opt out of two of these contests. Oh, it isn’t wise to do so. But if you’re happy with your cities, you can make like a racist secular humanist and tell religion and diversity to shove it. When the fourth epoch concludes, only the highest of your three scores is worth anything. If you’re a dominant religion without any cities, no big deal. Diverse city-state? Sure. Or, yes, you could play as the usual empire-builder that controls most of the map. The only danger is that someone might mobilize the global philosophy against your chosen sphere, knocking it out of the running entirely. This is why everyone hates moral philosophy professors. While specialization is supreme, diversification prevents your theocratic state from looking silly when everybody turns agnostic.

One would be overly discriminating to expect any game this ambitious and this broad to be without flaws; indeed, that there are so few is almost miraculous. Still, its sandbox nature yields the occasional stinking clump. A strong early religion can award lots of foundations to a single player, often leaving others frustrated. Similarly, the game only moves forward by increments when civilizations challenge the gods — and this is a testy process that often takes a backseat as players jockey for position in that epoch’s race.

Impressively, some of Origins’ weaknesses are also advantages. The trade action, for example, lets players exchange technology, release pawns from less-developed segments of their brains (hmm), or suppress dissent. This is a common irritant for leading players as a rival in second place elevates those trailing behind. Annoying and game-delaying, perhaps, but this is far more than a catch-up mechanic. It’s symbolic of developing nations brought into orbit around powerful patrons, effectively becoming counters in a game far above their heads — until they’re caught up and poised to become a world power in their own right. At times this, along with the deterministic victory conditions, can make the game’s early moments feel somewhat trivial compared to those of the final epochs. But this is also a mercy, keeping everyone invested for the entire four- or five-hour duration.

I asked for something different and Bios: Origins delivered. This is far more than a civgame. It’s a game about civilization. About disease and disaster, about domestication and cultivation, about herdsmen and explorers, artists and artisans, priests and philosophers. About how cultures can be hijacked or realigned. About a species in ascendance. If Genesis traced A to B and Megafauna traced B to C, Origins goes from C all the way to here. This is a game about humans. For better or for worse, Origins is about us. The scope of most civgames just shrunk a few inches.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

Posted on February 11, 2020, in Board Game and tagged Bios: Origins, Board Games, Ion Game Design, Phil Eklund, Sierra Madre Games, The Fruits of Kickstarter. Bookmark the permalink. 16 Comments.

Great write-up as always.

I’m a big fan of Bios Megafauna and the recent Paxes. But when I read the rules for Origins and fiddled around with it on Tabletop Sim, it never came together like those other games did. I wasn’t able to “see through” the game, see how one could make clever or inventive plays. It just felt like I was moving cubes around in a way that I’ve never experienced with an Eklund/SMG game.

You didn’t talk much about the minutiae of the actions, but does the decision space open up after the first epoch? How different do players become once they specialize, and do the actions begin to feel truly meaningful?

It opens up significantly. That first epoch is pretty much about prayer and encephalization, with some migration and *maybe* a city or two. The second epoch allows pretty much everybody to start moving up the tech tracks in different ways, found cities, and begin specializing. The first epoch still “matters,” but it’s all foundational rather than impactful in its own right.

I dig the series and look forward to Bios:Origins. Your reviews are always the final word in quality for me, so count me in for a near-future purchase. Always a strange delight deciphering an Eklund game from just the manual and some online clarifications. And the Origins theme resonates far more with me than does that of the series’ start.

Keep up the good work.

Thanks, Mike. This series has definitely grown more interesting to me with each entry. I’m considering playing the entire trilogy through the linked setups, and maybe writing about it. The only downside is that I’ll have to slog through Genesis’ vocab test again. Ugh.

Good write up (again!). I’ve also been contemplating playing through the games shelf from Bios:Genesis to High Frontier… Something I’ve mentally been categorizing as “Eklundageddon” after how my last games ended.

I’m definitely hoping to do a feature chronicling my group’s journey through the Bios trilogy. High Frontier… we’ll see.

Also, feels like Pax Transhumanity should be somewhere in between Origins and HF!

To be honest, this was the title in the Bios series that I was the least interested in. I basically just ordered it to complete the trilogy. Thanks to your review I’m now actually looking forward to it 🙂

I’ve backed the “High Frontier 4 All” kickstarter and I’d also love to do a “Eklundageddon”; I just fear, it would take well over a day to finish…

Oh, we wouldn’t play them all in one day. The current theory is we’ll play the trilogy across a month. There’s a limit to how many Eklund designs I can internalize in a single week.

I’ve always respected your reviews so much and continue to do so. I’ve put many games on my radar (and many off too) across a long while, however this one was a massive flop for us! Probably the most disappointed I’ve been in a game in a long time. So many reasons to list in a short comment, but gosh, this will not be returned to!

Thanks for the review though. I wonder what it was that gave your group a fun factor for this one? Was it the building of a card tableau? All the various potential actions to explore? I know the review is right here, but I still ponder about how you arrived to your review outcomes on this one ~~ so confused!!

I know Phil has been said to say that this is his best game, which makes me feel a little sad to even write this. He’s clearly very talented and I can see the work and skill that has gone into it.

Feel free to list your reasons! Sometimes that’s just how things shake out. I will say, despite my appreciation of this one, it certainly isn’t my favorite of Eklund’s games. If I had to nail down what I like best about it, I would probably name two things. One, I like that it’s a civgame that steps away from the usual “geographic growth is the only thing that ultimately matters” view of civilization, and two, that it makes good on human history as a set of competing philosophies, especially in how it gamifies those philosophies within the gamespace.

I think one thing I’ve learned from your reviews is definitely that you love games that ‘make an argument’. I think this is something you might have said yourself? I think this game definitely makes an argument in the sense you mentioned i.e. it steers away from simple geographic growth/ looks at human history through the ideological lens of civilisations.

I think Phil must be a spectacularly intelligent guy. It was definitely the first rule book where there were footnotes at the bottom of the page referencing real human history as you might see in a textbook.

I think ultimately this game was just not fun to play (for us), which made the rest of the games intelligence just lost on us. The rulebook reading can not be underestimated here. It is both the most logical, but also the most difficult rulebook I’ve ever read (and I’ve read a tonne). The only way I can describe it in retrospect, was that it felt like it written for an artificial intelligence; it was not written for ease of consumption. The rules are both simple, but extensive and difficult to consume.

There was a lot about the graphic design that just made the game difficult. For example, the board made it super hard to, at a glance, see what was there. E.g. The catastrophe events all looked the same and were sometimes covered up by tiles. Probably the biggest graphic sin, was when you add the cards to your tableau. The card is a reasonable size, but the symbols from which the entirety of the game are derived, are so, so, so, so very small. You end up staring at these tiny symbols throughout the entire experience – not fun given its at the core of the game play. Further, literally none of the symbols describe what they actually do. I ran an experiment with friends where I covered up the meaning/ description of each rosetta symbol, told them about the game’s context and asked if they could derive either what the symbol was about or what kind of gameplay effect it might have. Needless to say, no-one was able to get close with anything.

I wouldn’t normally have a load of negative things to say about a game’s tactile-ness, but this game felt really flawed in this respect and it REALLY detracted from the overall experience and flow of the game for us.

But even mechanically, it just wasn’t fun. So much of the game just felt really same-samey. While I like the idea of trying to approach your civ expansion through different means i.e. spirituality, industry or war etc. the ultimate mechanisms that achieved these different goals just felt too identical. Preaching and warring just felt so samey that I couldn’t tell the difference most of the time. The various tech tracks kind of felt different, but perhaps still not enough? Still undecided on that bit.

The end game really didn’t feel inspiring either. It essentially becomes a tug of war over the global philosophy, which will decide which societies will score big (or not). While this sounds cool from creative/ intellectual perspective, mechanically it just didn’t really feel all that fun in reality.

I suspect that my enjoyment of the game would go up with repeat plays, but ultimately I don’t think it would go up enough to ever warrant continued play when there are so many other great games around. One in particular, which you put me on to… Time of Crisis. Now that is entertaining FUN!

Sorry to hear you didn’t get along with it, Joaquin!

Pingback: Review: Bios: Origins (Second Edition):: More Than Merely a Civilization Game (a Space-Biff! review) – Indie Games Only

Pingback: Absentee Civilizations of the Inner Sea | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2020! Parallel Dimensions! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Twilight Iconographies | SPACE-BIFF!