Laying Pipe

I have a theory that the hallmark of a heavy economic game is the ability to take out a loan. Not just any loan, mind you. This isn’t some family loan, a hand-wavey Pay me back when you get the chance, son. No, this is the loan a banker makes when he’s got you over a barrel with one hand and is clutching your short hairs with the other. The sort of loan that makes you wonder why you decided to lay track instead of becoming a financier.

Pipeline lets you take out such loans. The first time will wring a gasp-worthy 33% interest out of you, and each additional loan compounds from there. By the fifth visit to Mr. Manager, Sir, you’ll be required to pay back 400% of what you borrowed. Not that you’ll need five loans. But the option is there, tantalizing like an apple in the Garden of Eden.

Does Pipeline live up to its allure? For a while, sure.

It isn’t uncommon for an economic game to accelerate at a sharp angle, and in that regard Pipeline is no exception. First you’re playing for nickles and dimes — don’t forget to clip your coupons — and before you know it you don’t even know what to do with all those warehouses of cash. But let me impress upon you how difficult it is to build that first warehouse. Like they say, it’s making your first billion buckaroos that’s tough.

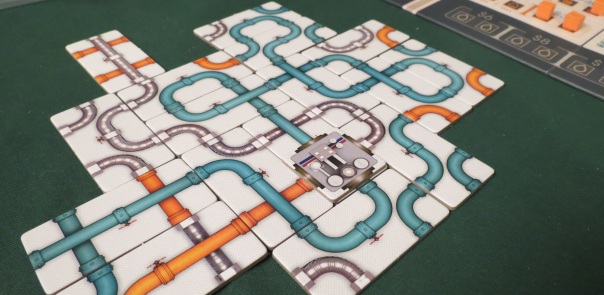

Surprising nobody, Pipeline is about building the most efficient possible oil company. Also surprising nobody, the necessary initial investments are steep enough that you won’t be seeing any mom and pop outfits springing up. Please pay attention, because I’m going to mention some numbers, and instead of blipping past them as you read, I want you to internalize each item. To jump-start an oil company, you’ll need crude oil, and every barrel in the early game will run you from $5 to $10. Also pipe, carefully arranged into a functional network, which can be bought at a premium for $15 or $40 from private contractors, or stripped out of the government’s tangled and aging network for a bit less. Tanks for holding your oil — and your purified gas — run anywhere from $5 to $15 per. And that’s before we discuss investing in upgrades, the time cost of certain actions, or the need to pay your workers extra for double shifts.

Do the math yourself. In order to lay a few choice segments of pipe, buy crude and the tanks to store it in, and process it into the fumey gold that gas station attendants everywhere will merrily huff, what are your estimated costs? At least $100? Double that?

Try doing it for $40. That’s right, forty dollars. Or forty million dollars, or whatever Pipeline’s money chits represent. Right about now, those loans are looking pretty attractive.

Figuring out how to get your oil company off the ground is the first act in Pipeline’s economic quandary, and it’s arguably the most compelling segment. The game as a whole plays out over three years, with each year reducing the number of actions you’re allowed to take — eight, then six, then a measly four. This reduction neatly represents the need to stay competitive in an accelerating market.

Here’s what I mean. Early on, you’ll be solving the conundrum I proposed above. To turn a profit, you’ll buy as few pipes as possible, as few barrels of crude, as few storage tanks. Meanwhile, you’re also solving the puzzle of what to do with each action. Normally you only get one per turn, whether securing contracts and loans, buying pipe from stores or the government, investing in upgrades, or visiting one of the country’s four oil markets. Eventually, however, one action isn’t enough. You’ll want to jump between one action and the adjacent offering. You’re still limited on selection, which means you’ll need to plan ahead. But you can effectively transform one turn into two turns.

But the privilege is going to set you back $10.

In other words, a full quarter of your seed money. But when every action is both limited in what it can accomplish and consumes time on the game timer, you’ll want to be taking those extra actions as soon as possible. Doubly so when one of those actions is to refine your crude oil into something worth selling. It goes like this: you grab your meeple, set him on a tile in your personal network of pipes, and if you have enough linked segments of the proper color running through that tile, you’ll move matching cubes from crude to semi-refined, then medium purity, then eventually octane a road warrior would proudly guzzle. Each bump in purity turns more of a profit, whether sold at market or fulfilling contracts and special orders.

But that refinement costs an action. One more delay. One more bottleneck.

The solution is automation. This is what propels Pipeline into its second half. By purchasing a machine (minimum cost: $20) and attaching it to your pipe network, you unlock a new option. Rather than spending an action to personally manage the purification process, you can simply spend $15 at the end of your turn to run your machines — and all the pipes attached to them. Just like that, your engine is running itself. Buy cheap crude, plug it into your machine, and with a microwave ding! it’s refined oil ready to be sold. Keep improving your pipes and you can even purify a single barrel multiple levels in a single go.

Automation is the inflection point between a company bleeding money and a company with plump investors banging at the door. I mentioned the sharp acceleration of heavy economic games; in Pipeline, your profit growth often resembles a rocket ship escaping orbit. Before you successfully feed your machine, you’ll likely be living hand to mouth. Sales produce money, money produces pipelines, pipelines produce sales. As soon as your network is automated, you can spend like a trust fund baby in his first semester of college. Double actions, network expansions, tanks to hold all the barrels you’re buying and purifying. Not even the sky is the limit.

Right away, this accomplishes two things. First, it gives you a definite goal to strive toward. The difference between a manual network and an automated one is so significant that it’s nigh-impossible to imagine a hands-on company succeeding against one operated by software and flashing lights. Remember, each year offers fewer actions. The obsolescence of manpower is coded directly into the game. This is the era of the machine. To thrive, your network must be given over to that which does not complain or tire or request maternity leave.

The second thing, however, is that even the slightest delay can see you falling irrevocably behind. Not that I’m complaining. This is as thematically appropriate as a hand-threshed wheat farm offering no competition to a mechanized agribusiness equipped with synthetic fertilizer, combine harvesters, silo elevators, and industrial-scale winnowing machines. But it also means your first goal is often your final goal. As long as you can automate early in the game, the resulting boom will see everyone else at the table eating dust. It effectively divides the game into haves and have-nots, competing in two different games for two different levels of score.

Of course, Pipeline clearly wants to be the sort of game where a misstep can permanently flounder your chances of success, so all’s fair in that regard. But unlike certain other heavy economic games, many of which feature multiple paths to success, this need to automate isn’t so much singular as singularity — there’s no escaping its pull. There are myriad criteria upon which your company will be judged, including “valuations” — variable scoring cards, basically — and these might seem to offer an alternative. But in practice these goals are most easily striven for when you have a steady profit stream, making it easier to pivot once you’ve reached full automation rather than running a boutique operation early on.

Let me put it another way. A decade ago, video game critic Tom Chick discussed a “parabola of fondness” in reference to strategy games. This so-called Chick Parabola began by ranking its level of enjoyment at the bottom of the chart: the strategy is opaque, the rules haven’t clicked, even the user interface is muddied. As you learn to command and eventually manipulate the game’s systems, your enjoyment increases, because the process of mastering something is nearly always thrilling. After all, if there’s anything games do well, it’s providing something you can make progress toward mastering within a digestible timeframe. At a certain point, however, that arc of enjoyment often bends downward. Why? Well, in Chick’s case — speaking about digital strategy games, keep in mind — it’s because there isn’t anything else to master. The systems are transparent, the optimal paths are obvious, the A.I. is too weak to put up any real resistance.

Most board games take steps to mitigate this downward turn. Variability is one. Pipeline has your back there, providing ample scoring opportunities. But this applies mostly at the micro-level rather than at the macro. Although you might prioritize orange pipelines over teal, or variety over specialization, or gas tanks over quantity of machines, Pipeline’s main arc always hinges on that need to shift from manual labor to automation. Again, this is both mechanically and thematically sound. But it’s such a dramatic shift in tempo that coming in second is like a full-strength tuba blat at the wrong moment of a concert. Instead of directing the course of your energy empire, you’re mostly fiddling with pipe arrangements and fretting over whether you can afford all those barrels now or need to save some money to run your refinery.

To be clear, these are perfectly good turn-by-turn actions. It’s the broader picture that’s uncomfortably narrow.

Enter another mitigating agent, that of player interaction. In short, perhaps players can drag at each other where the game state will not. Sadly, this is where the intriguing strategic arc of Pipeline stumbles. Placing your worker on a spot doesn’t block that spot. And in fact, such a thing would prove far too disruptive for this game’s measured economy. But taking an upgrade does block that upgrade path from consideration for the year — plus a second path, if its purchaser so desires. Depending on the random turn order of the setup, this might even block off a later player from any chance of seeing the highest tier of upgrades. It’s a spare note of player intersection applied at a peculiar juncture, taking the game’s absolutely wonderful and game-shaping upgrades and making them far rarer than they should have been, rather than, say, letting you undercut a rival who happened upon the pipe junctures that automated his network two turns before you.

(As a side note, the upgrades, like many of Pipeline’s best features, are spot-on. Some revolutionize how you approach each turn by letting you take a second action for free, earn more cash when fulfilling contracts or selling to the market, or artificially lengthening your pipe network. Even those that “only” provide free doohickeys are worthwhile, saving you both money and time. It’s a shame they’re locked away so rapidly.)

In other words, Pipeline includes player interaction where it’s least interesting, and lacks it where it might have landed a punch. The result isn’t heads-down play. Everyone’s actions have plenty of impact on one another, altering the cost values of nearly everything you can purchase or sell. Rather, the result is a game where your only means of interaction is filtered through a third-party marketplace that does little to police runaway leaders or even allow for mild undermining. As an economic race, it’s nail-biting — but often only to the conclusion of the game’s first act, with scarcely any recourse once somebody has pulled ahead. There’s a reason the 18xx genre and other select economic games focus so heavily on stock trading, letting you weaponize your expanding economic powerhouse to weasel money out of other players’ gains. They offer the possibility of reversal or team-up, collapse or upset. No so thing is found in Pipeline.

If I sound negative about Pipeline, I should note two things. First of all, it contains a few elements that I found quite wonderful. The pipe-maze puzzle is a delicious way to write your purchases into relevancy, it feels great to correctly budget your cash down to the last dollar for a big turn, and, if pulled off correctly, its three-year arc is both satisfying and a stark commentary on why some companies succeed while others crumble. Mechanize, son.

Furthermore, my complaints might not matter in today’s hobby scene, wherein games are often only played a handful of times before they’re replaced by something shinier. I’ve invoked the Chick Parabola to prove a point. Namely, that Pipeline is perfectly wonderful when you’re learning the ropes. The path to mastery is lined with crunchy decisions, careful budgeting, and entire piles of tiny money tokens. It’s just that Pipeline’s parabola bends swiftly, and it isn’t long before there isn’t much left to see.

Bottom line, it’s excellent for a play or three. Beyond that, despite being an effective tutor on the value of proper industrial mechanization, it fails to automate.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on July 2, 2019, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Capstone Games, Pipeline, The Fruits of Kickstarter. Bookmark the permalink. 14 Comments.

Thanks for the review

Happy to do it! And congratulations to you on designing a game that’s capturing people’s interest. I’ll be eagerly watching to see what you design next.

Great review, Dan. This mirrors many of my own thoughts. Pipeline does all this great stuff, but it quickly feels “solved.” We’ve found that keeping upgrades unlocked helps it feel more dynamic. You’re completely right that locking them off was a weird inclusion.

I considered using the word “solved,” but ultimately decided it was too strong. There’s still plenty to manage in each play, and the valuations go a long way toward mixing it up — provided enough players hit their automation to make the second half worth playing. I should try freeing up the upgrades; they really are a highlight, and I’d love to see more of them.

Knowing the basic steps for creating an efficient engine is essentially the bare minimum skill set required in the transition from a mostly multiplayer solitaire puzzle game where you are fighting the board to a game where you are actually playing the other players. And with no piggyback or catch up mechanisms, if players are of unequal skill or fail to keep up, tension can and probably will be lost. As mentioned in the article this is the downside of avoiding these mechanisms. So unfortunately as the onus to maintain tension begins to shift from the board to the players there is potential for (and in the author’s case did lead to) poor player experiences.

Either way thanks for giving my game a shot.

I suppose I made an assumption that “solved” is in reference to playing enough games to know how to create an efficient engine. If it wasn’t my response will make no sense.

Hopefully in my next design I’ll be able to do a better job easing players from competency in the initial puzzle part into the more interactive part so I don’t lose part of my player base during that transition. There are certainly tradeoffs and weaknesses of the Pipeline design that I’m learning from.

There’s a perennial discussion about modern Euros and whether they tend toward being “multi-player solitaire” (MPS), and why that might be the case. Proponents of such games obviously gravitate to the non-combatitive gameplay, but one of the things they say in defense of MPS is that they /are/ interactive, but in a way that you only start to see after many plays. It sounds like Pipeline may be such a game.

But the thing those people go on to say, and that surprises me, is that this type of interaction — the subtle and indirect blocking — is actually superior to games with more direct interaction. I’ve never been persuaded to that view, and I wonder if Dan would also be skeptical of it; at least, that’s what I sort of hear him saying in his review. What this view seems to miss is that between the polar extremes of “direct combative interaction” and “subtle and highly indirect interference-type interaction”, there are tons and tons of interactive systems. I’ve never felt that games with such systems of interaction to be insufficiently rich, and more to Dan’s point, and the one you raise, they have the advantage of letting players experience the richness of the game’s interactive landscape from a pretty early time on the climb up the learning curve.

Maybe this sounds silly, but you’ve persuaded me to get this. My group barely plays new games more than three or four times anyway. I guess we like that sense of discovery.

Honestly, I think that’s where a lot of people reside in this hobby. And that’s fair enough! That’s the reason for my disclaimer. If this sounds interesting, it’s great for a few plays.

Reacting late, but I was deep in the Yucatan jungle for a few weeks.

I think Pipeline has tremendous replayability. Until you have played at least 4-5 games, you think the game is too tight, that is ends too early and that any mistake creates a severe case of runaway leader (or spiraling loser).

Then you start to see the nuances.

First: the game becomes very interactive. While the first games are multiplayer solitaire, from 5-10 games you start to see hard, tough moves from players. At first, you think only the upgrades are blocking moves, which is why you see so many new players complaining about the fact that you can block 2-3 upgrade paths. Then you notice that aggressively filling markets is even meaner. Meaner still is the move to buy out all the tanks. Or all the pipes of a color. Or wreck havoc in a government quadrant, leaving only isolated pipes. Or monopolize the contracts. Suddenly every action is interacting with everyone else’s and upgrades almost look too forgiving.

Second: as you play more often, then you start to see how to build this network. There are specific combos of 2 tiles that yield 5 segments, and so on. So now you start being efficient earlier, and machines are out earlier, then more machines are bought and scores get much higher (and then you had the “7”s, and even think of removing the “4”). But as you understand this better, then you notice how one well-thought move can block other players from getting this perfect network.

I think this one deserves investment. More than most games I own, it only reveals all it facettes with time, with several plays, until it morphs into this tough, tight, cruel (I almost wrote crude) and wonderful game that is so different than what you thought at first, that you ask yourself how you ever were so naive to think it would be so simple. You were Eli Sunday, now you’re Daniel Plainview.

Pingback: The Cargo Isn’t All That’s Curious About It | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Happy Trails to You | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: This One’s a Bear | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: In the Pale Blood Moon Light | SPACE-BIFF!