Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Board Games

Shasn. Oh, Shasn. Zain Memon’s 2021 board game occupies a strange place in my memory as a vibrant, unsettling, funny, and tonally inconsistent game, and I mean that in the most complimentary sense. At the time, its message seemed to be that politicians are opportunists of the lowest order. And, hey, fair enough. My country is currently ruled by a conman who sells presidential pardons like they’re skincare products. But is that something we need a board game to tell us? I doubt those who haven’t gotten the memo are playing imported board games.

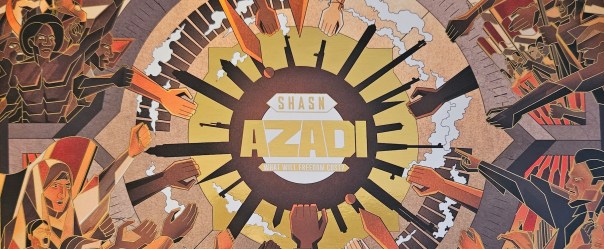

Here’s the thing. Shasn might not have imparted the most insightful message. But Memon has been plugging away at it in the background. Now, together with Abhishek Lamba, he’s released a sequel… expansion… thing. A standalone? Is that the right word? Who knows. Regardless of its proper assignation, Shasn: Azadi is twice as peculiar as the original game. Again, I mean that as a compliment. Mostly.

Settle in. This one’s going to take some doing.

Part One: Call and Response

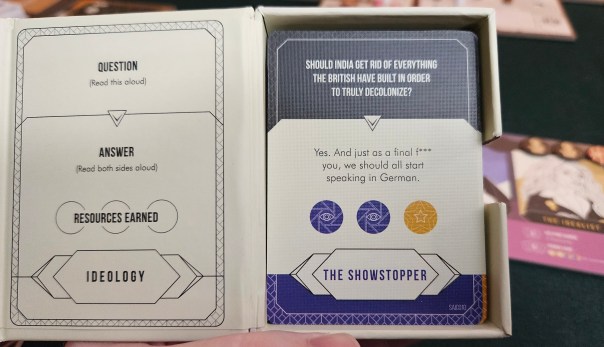

Every turn in Shasn opened with a question. As a general rule, these questions were hard-hitting, touching on topics as far-ranging as abortion, penal codes, human rights, ethnic cleansing, protected speech… anything and everything that might be posed to a prospective leader in an interview. The responses, meanwhile, were binary. Yes or No. Simple. Simplistic.

More than that, they were irreverent. Sometimes distressingly so. One by one, the game introduced serious topics only to lampoon them.

I plucked an example at random from the Egyptian Revolution set. Question: Should mothers be allowed financial custody of their children if the father passes away? (A) Yes. Women are fantastic spenders, they should be in charge of all money. (B) No. The Motherland can only flourish when the government takes care of its mothers’ finances.

Coming into Shasn cold, it would be easy to back away. What is this, one of those awful “offend everybody” party games?

Not quite. These Q&A sessions serviced the game’s intended message. Each answer fell into one of four categories. Broadly speaking, they represented archetypal positions adopted by politicians. Soundbites, basically. The Idealist might offer a platitude, something well-meaning but maybe not squarely positioned within the realm of the possible. The Capitalist would talk about the economy and the job market, how the children yearn for the mines, that sort of thing. Somewhat harder to peg were the last two personalities. Not because they aren’t recognizable, but because sometimes they blur into one another. The Supremo and the Showstopper. One for hard-line authoritarianism, the other for maximizing ratings. In my experience, those two tend to cohabitate.

Moreover, each answer provided a color-coded resource. Red for the Supremo, green for the Capitalist, and so forth. These currencies were all precious, necessary for purchasing the votes that would spread supporters across the game’s map. To win, then, one needed to play every side. It wasn’t long before even those with the soggiest of hearts started speaking out of both sides of their mouth, whether to access hard-fought resources or double down on a single category to unlock special powers.

To play Shasn was to become a politician. At least if you wanted to win. Was this a trite message? Sure. Worse, it was perhaps a self-reinforcing message. When we expect our politicians to say what they don’t mean, we begin to excuse them. Still, it provided an intriguing framework for a game about political animals, putting players on the spot and asking them to guess at the outcomes of any given soundbite.

Azadi begins with that exact same framework. When a turn opens, your neighbor asks you a question. Then you answer it blindly. You earn resources. You gain special powers. These are all identical to those from the base game. You can even use the same sets of ideology cards.

But Azadi takes those questions and reframes them in a crucial way. To explain how, though, we need to take a look at the ways Azadi differs from Shasn.

Part Two: The Board Game

Sorry, but we aren’t quite ready for the differences yet. Don’t worry, I’ll pump the gas.

Like Shasn, Azadi is a game about building support. You take the resources you earned from your call-and-response soundbite, spend them on voters, and then distribute those voters across the game’s double-layered map. Each region can only host a certain number, with majorities clearly marked. As soon as you hit the requisite amount, you flip your voters to their other side, locking in the region’s support. These are victory points. And they can be rather tricky to dislodge once they’ve burrowed in.

Gerrymandering plays a huge role in Shasn, and by extension it plays a huge role in Azadi. Whenever you have the most voters in a region, you can push a rival’s voter into a neighboring area. It isn’t uncommon to see little zoning wars break out, certain voters ping-ponging between districts. It also isn’t uncommon for supporters to self-sort into ideological zones. Why place a voter into an area where they won’t ever do any good? As an observation about how different regions of the same country tend to polarize as people seek out those who think like themselves, this was always more insightful than the “politicians are scum” stuff.

Special powers also play a significant role. These are unlocked by gathering a certain number of soundbites in each category. With three Capitalist cards secured, it’s now possible to trade one resource for any two others. Only once per turn, of course. The game isn’t entirely broken. But it’s a little statement on how money can overcome a whole lot of shortcomings in other arenas. The same goes for the other spheres. At five cards, the Capitalist begins evicting voters from the board, sending them to other regions. That’s nicer than the Supremo, who bullies them out of existence altogether. The Showstopper turns gerrymandering into an art form. The Idealist tries to convert rival voters rather than removing them, although this is costly.

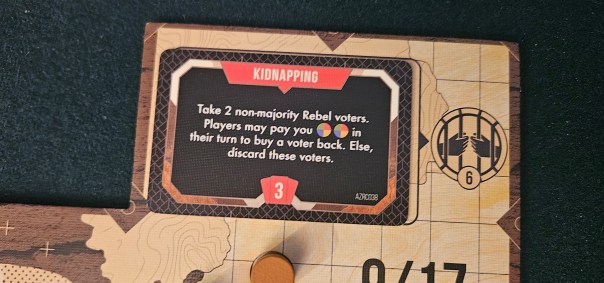

This was the core gameplay loop of Shasn, and it’s preserved more or less intact in Azadi. Actually, it’s a little simpler in Azadi. In addition to voters, Shasn allowed players to purchase conspiracy cards. Basically, conspiracies offered ways to manipulate the board outside the regular loop of buying and gerrymandering voters. Conspiracies are gone in Azadi. As we will see, to mixed effect.

So what’s changed? First, the board is modular. It’s a small thing, but the manner of its modularity is important. When the game opens, there are only a few regions. It’s only as the game continues that it expands outward. This forces players to cluster together, contesting those starting regions, rather than retreating to their own corners right from the beginning.

This also speaks to the larger structural change that undergirds Azadi. Namely, that this isn’t a game about domestic politics. It’s a game about revolution. Which means that there’s another faction at the table, one controlled by everybody and nobody. This is your imperial overlord. They are stern masters, their supporters are numerous, and you want them out.

Now we’re cooking with enough gasoline to make a whole crate of Molotov cocktails.

Part Three: Azadi (or, Every Individual’s Fucking Birthright)

Azadi, like Shasn before it, isn’t some made-up fantasy word for a board game. Where “Shasn” was derived from the Sanskrit word for “governance,” Azadi, meanwhile, is Persian. It means freedom.

Or, to use the game’s definition: AZADI (noun), origin: Persian. 1. Freedom, Liberty, Independence. 2. Every individual’s fucking birthright.

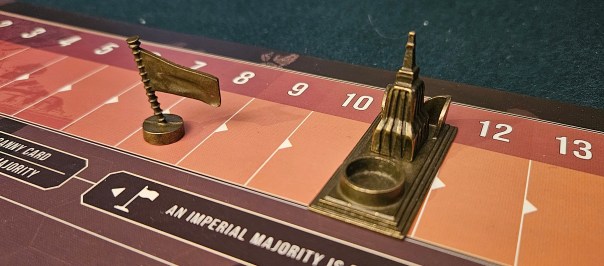

When Azadi begins, your country’s azadi is very limited indeed. On a track beside the board, you can see the overlord’s presence, way up near the top. Down at the bottom is your azadi, a revolutionary flag. This flag shifts upward when you gain control of a region through the regular rules of Shasn. Buying votes. Creating majorities. Grassroots action. There’s even a new rule that allows players to form coalitions, adding their voters together to achieve a majority together.

It won’t be enough.

There are three main problems facing the table. First, this isn’t a true cooperative game. In the same vein as revolutionary titles like Bloc by Bloc or Molly House, there’s a veneer of cooperation that proves tenuous when it comes to proclaiming an actual victor. Everybody represents their own distinct faction. And while you may agree that the overlord must be ousted, what precisely to do with any newfound freedom is hotly contested. Any coalitions, then, will be temporary, while your voters promise to stick around. This turns every placement into a double-edged sword, cutting against the overlord right now, but also against your current comrades in arms later.

Second, the temptation to collaborate with the overlord is ever-present. As the game progresses, your resources are steadily drained, not only by the demands of voters, but also by the overlord’s distant taxation. Those call-and-response cards always award three resource tokens. The overlord, on average, takes two. The leftovers aren’t much to live on, let alone build an independent nation.

Now, you could bide your time. Once you reach two matching ideology cards, you begin to earn a passive income. But the game is also played on a timer. Dither too long and the window will slam shut. At a certain point, action must be taken.

Hence, collaboration. By adding imperial voters to the board, you earn resources. Maybe even a tidy heap of resources, one for every region you add that imperial voter to. Sometimes this isn’t a big deal. If somebody already has a majority in a region, for example. At other times, it’s the act of a quisling, blocking an upstart comrade from claiming a zone. Either way, this is enough to kick the game into gear. Already on turn one, you’re making hard decisions. Whether to work with your overlords. Where to collaborate. Where to make concessions. How to ease the tensions with your peers at the table.

Still. It won’t be enough.

As in the original Shasn, every region in Azadi has one special space. Called “volatile zones,” these were originally used to draw event cards. Now, once occupied, they spark recriminations from the overlord.

This is perhaps the game’s flashiest addition to the original formula. As soon as a voter occupied a volatile zone, you draw a very special, very weird card. Really, they’re more like small folders. This presents a historical problem. Continuing with our example from the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, you might draw a card about the Port Said Massacre. “To punish the Ultras for their role in the revolution, the police trapped and killed countless football fans,” the card reads. “We can’t let them stamp us out.”

This card now pulls double duty. First, it adds an event to the region where the volatile zone was triggered. These represent government crackdowns, making it harder to add voters to that region. In the case of our stadium massacre, the corresponding card is a seizure. To add more voters, one of the voters already there must be converted into an imperial supporter. Other recriminations might include censorship, forced conscription, curfews, death penalties. The tools of the imperial trade, brought to bear on subaltern bodies, each complicating the ordinary task of gathering support in their own unique ways.

Now, these edicts can be opposed. By spending resources — always with the resources! — you earn another resource, infamy, that can be spent on revolutionary actions. More importantly, this gradually wears down the imperial control of that region. Oppose the edict enough and it will disappear altogether. On the track, your azadi ticks upward, bringing you one step closer to earning your freedom.

Even this won’t be enough. But that first imperial attack card, the little folder, isn’t gone. Instead, it has been spread open and placed to the side of the table. Now it sits there, offering different responses to the crisis. To return to the Port Said Massacre, you’re given two options. The first is riots. By discarding a voter — throwing your bodies against shields and batons — you can erode the overlord’s support. The other option is patronage. Memorials to the stadium martyrs. Vigils. Shrines. This option requires you to spend those precious infamy tokens, effectively trading away the prospect of violent revolution, but still showing strength.

Every crisis in Azadi is different. Not all of them demand violence, but they do speak to the need for direct action. At some point, organizing voters isn’t sufficient. In the case of the Port Said Massacre, it takes riots or vigils. Other crises present their own possible responses. Assassinations or lawsuits. Underground newspapers or hacked firewalls. As players, you’re free to pursue either option. These decisions present lingering consequences, represented as new action cards added to the map. Little legacies of how you chose to walk the walk.

No matter the precise response, however, the outcome is similar. Your azadi slowly swells upward. The map expands, bringing new regions and allies into the movement. And eventually, if you move quickly enough, if you’re clever with your collaborations and concessions, if you work with your comrades, freedom can be won. That little flag clinks into the little overlord token. In thematic terms, the oppressors are sent packing.

The game isn’t over. If anything, this is when Azadi reaches its inflection point.

Part Four: Something Ends, Something Begins

The instant the overlord is ousted, Azadi offers some respite. Think of it as an interlude. A time-skip.

First, you see what manner of nation you’ve built. Everybody takes their answers to those call-and-response questions and adds them up. These are the contrasting visions of your country’s founders, whoever they might be. Revolutionaries and essayists and generals and artists and collaborators. Or, in Shasn’s terminology, Capitalists, Supremos, Showstoppers, and Idealists. These ideologies are tallied to become the basis for your new government.

Depending on the first- and second-place winners, a pair of distinct visions emerges. Now everybody gets to vote. The currency this time isn’t voter pieces; it’s the contributions everyone made to the revolution. The outcome is everything. Maybe you’ll choose to burn bridges with the outside world, retreating into isolationism. Or perhaps you’ll establish an oppressive theocracy. Or a libertarian paradise that excludes the filthy masses. Or a democratic beacon on a hill. Or a flawed democratic state with limited enfranchisement that likes to tell itself it’s a beacon on a hill. Whatever the outcome, this sets new rules for the game going forward. Special abilities. Single-use monuments. Whose ideology cards receive special affordances, and who gets included. The usual board game stuff, but developed in direct response to the actions you took across the preceding ninety minutes.

Honestly? It’s sublime.

One of my critiques of Shasn was that it examined how politics function, but ignored what politics are for. Azadi rectifies this omission. All those goofy call-and-response questions suddenly matter. And not only in game terms, but as reflections of ideology. They’re your Federalist Papers. Your Declaration of the Rights of Man of the Citizen. Also, unfortunately, your delegation on the preservation of slavery, whether at home or in the colonies. The result is a half-wrought constitution, some new mode of governance that’s better than what came before, but also profoundly imperfect.

Also, crucially, it’s still under construction. Because what comes next is closer to the original Shasn. All the old coalitions are broken. Imperial voters (usually) disappear. Now everybody is out for themselves. It’s back to the gerrymandering and voter suppression and all that. The revolution has slouched back around to eat its children.

It sounds cooler than it is.

I mentioned earlier that Azadi has done away with the conspiracy cards. It’s okay if you don’t remember. That was many words ago. But the point stands. The portion of Azadi that comes after its tense first act and that incredible intermission is something of a letdown.

At best, it’s a slog. An interesting slog, perhaps. You’re still gathering resources and buying voters and doing the gerrymandering thing, and the rules have been tweaked by the actions you took as a revolutionary. But it’s straightforward in a way that the game’s first half was not.

At its worst, the back half of Azadi is perfunctory. In such a case, it’s already clear who has secured the most majority votes, there’s really no stopping them, but there are still a few rounds to go before the map has been filled in enough to bring home the final tally. Sure, it’s possible to call it right then and there. But then you won’t get to see all those little consequences play out. After all that investment, it would be a shame to not finish.

Even so, it’s a disappointment all the same. Something to mix up the final few rounds wouldn’t have gone amiss. Like, say, some conspiracy cards to keep everybody on their toes. Too bad the deck from the original game is so ill-suited to the myriad possibilities coming out of the game’s revolutions.

But. Still.

Azadi is a remarkable achievement. I mean that. Even when it stumbles. Even when its merger of bad party game and serious revolutionary manifesto put themselves at odds. Especially then. Because this is what politics are for. Awkward coalitions, strange bedfellows, bills of rights that strive for universality but leave out the untouchables, or the women, or the slaves, or religious minorities, or whoever. Please don’t mistake this for watery centrism masquerading as realism. There are grand outcomes, too. It’s just that they’re as mired in the muck of contrasting opinions and methods and sometimes violence as any other possibility.

Which is to say that Azadi is messy the way people are messy. The way countries are messy.

But both people and countries, to invoke Hemingway, can be fine things, and worth the fighting for. That, I think, is the takeaway here. Azadi makes no bones about its position on its messiness. Not every outcome is the same. The troubled democracy is not the equivalent of the iron-handed tyranny. Azadi is every individual’s fucking birthright. For such a game, for such a vibrant, unsettling, funny, and tonally inconsistent game, I can take the slow denouement with the exemplary meditation on liberty and nation-building.

Just, you know, never again with five players. That took forever.

A complimentary copy of Shasn: Azadi was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read about which films I watched in 2025, including some brief thoughts on each. That’s 44 movies! That’s a lot, unless you see, like, 45 or more movies in a year!)

Posted on February 12, 2026, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Memesys Culture Lab, Shasn, Shasn: Azadi. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

Hi Dan,

Yup, it’s happened again… Am wondering if it’s something to do with the way Outlook for Android deals with links on email (even though It’s never had this problem before?), but everyone else’s email links seem to work just fine …?? 🤔

Very confused.

All the best,

Alex

I’m sorry. =(

I enjoyed reading this review. I agree with a lot of it. I don’t think I can buy it because I can’t convince my board game group to play again and go through the QnA part when you already know how to game it. The fun is in the gerrymandering! I’m exploring house rules to help speed up the game to accommodate 5 players

Incredible review – thanks Dan. I never played the original, but sounds like I missed out on a doozy. This new version sounds even more interesting. I had purchased John Company because of the weird, wonky, yet scary reality and commentary it presents, but I was never able to get it to the table because it’s just too long. Maybe that’s the case here? I hope not. I just love games like this that are so out there and have so much going on.

Yeah, this is shorter than John Company.

This is the third time today that I’ve seen ‘infamy’ or ‘infamous’ used in a board-game description in a way that suggests the misunderstanding in the movie Three Amigos!: “Oh, Dusty. Infamous is when you’re more than famous. This man El Guapo is not just famous, he’s in-famous.”

Sounds absolutely fascinating! Thanks for the review.

Thanks for reading!