Cube Shuttles

The forthcoming Stellar Ventures is nothing if not wildly ambitious. Its creator, Pontus Nilsson, has designed both cube rails and 18xx titles, and is now mashing those systems together — along with the faintest whiff of 4X space opera — into a game that sees joint-stock firms crisscrossing entire star systems with logistical networks.

Also, the space shuttles sometimes rust. Just in case you were wondering what you were getting into.

For those who haven’t played cube rails or 18xx, first of all, STAY AWAY FOR YOUR OWN GOOD. Thanks to train games, I’ve seen families bid farewell to spouses and parents, attended game groups in open bewilderment at the disappearance of old friends, and witnessed youngsters develop a twisted sense for how capitalism operates.

But if you must persist, Stellar Ventures represents a slender crossover in a brand-new Venn Diagram. The first circle, cube rails, is a genre of sky-high abstractions about nascent train networks that tend to play quickly, feature lots of auctions, and obviously include a zillion cubes. I’ve even written about a few over the years. 18xx, on the other hand, is a series of dense five-hour-plus simulations that transforms people into their worst selves. I’ve declined to write about the things mostly out of consideration for my family’s safety, although if we’re ever in a secure location I’d be happy to share my misadventures trying to tackle the genre.

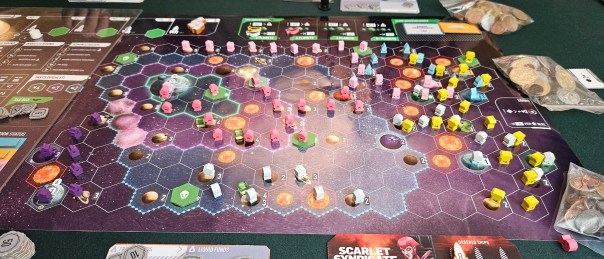

Stellar Ventures is a blend of the two, although I’d put it 80/20 in favor of cube rails. The gist is that players adopt the role of investors and managing partners in interstellar corporations. These corporations are principally interested in transit and extractive mining, enterprises that go hand-in-hand, just like here on Earth. At any given time, you can hold shares in many companies, either doubling and tripling down on the fortunes of a single company or building a diverse portfolio that accrues smaller but less risky payouts. Meanwhile, holding the most shares in any given company will confer a managing stake, letting you choose the placement of its stations and colonies.

Corporations earn little bonuses, first when they’re purchased and again if they sign The Agreement.

For aficionados of cube rails, this probably sounds like business as usual. The considerations are warm in their familiarity. Each sector can only accommodate so many stations, making it prohibitively expensive for second- and third-comers to build over already-occupied territory. At times, the proceedings take on the tone of a race, everyone rushing to push their favored companies onto high-value planets. There’s even some room for sabotage, especially if you snag a company share on the cheap and build a few stations to nowhere. But for the most part, you want your companies to thrive.

It’s the details that set Stellar Ventures apart from its terrestrial peers. For example, it isn’t enough to establish networks. Colonies and stations establish your company’s mining score, an overall tally that sets their base value. But they also need to move their goods to other worlds. This is where ships come in. By ordering rockets, a company’s shipping tally also ticks upward. When dividends pay out, it’s the lower tally between mining and shipping that sets the amount.

Okay, that doesn’t sound too bad. But this simple binary between mining and shipping can be deceptive. The ships themselves are volatile. Over time, those single-digit shuttles give way to two-points shippers, then three, then five, then eight. But at regular intervals, the invention of a new ship will obsolete a lower-value ship. Just like that, all the ships in your hangars are scrap metal. Devotees of 18xx will recognize this as “locomotive rusting,” an idea mined in multiple titles. When spacefaring technology leaps forward, it’s entirely possible that some companies will get swept into the dustbin, their older ships disappearing entirely and their shipping score bottoming out. At least until they scrounge up some investment money to upgrade their fleet, anyway.

At times, these moments are painfully punitive. Stellar Ventures is a rather phase-laden game, with companies and then individual investors each taking a turn. It’s entirely possible for one company to engineer a revolution in rocketry that tanks the dividends of the next company in line. This is nothing new to either cube rails or 18xx, as both systems are built on letting players live with their errors. Rather than offering catch-up mechanisms or rubber bands, the rich get richer and missteps send players tumbling into a debt spiral. Still, this lands differently in a two-and-a-half-hour title like Stellar Ventures than your usual single-hour cube rails game.

But this brings us to some of the game’s more interesting innovations. Because while it’s still possible to find oneself in command of a failing company, here there are a few avenues for attaching zero-g suspensors to one’s bootstraps.

The first is the idea of alien tech. As your companies explore the sector, they’ll come across many alien worlds. Some of them belong to an ultra-advanced race that offers The Agreement. The Agreement — which should always be invoked with due gravity so that everyone at the table can hear its capitalization — is a devil’s bargain that awards significant advantages but also threatens to rob your company of any value upon the session’s conclusion.

First, the advantages. There’s an immediate cash payout for every share in the Agreement-making company, and that payout only gets higher if you’ve made additional contacts with the alien race before shaking their tentacles. This imbues a company’s expansion with real tension, especially if its profits are tapering off and investors are hoping for an immediate buyout. As the managing partner, declining to sign The Agreement, whether because you have other plans for the company or out of hope of reaching yet another alien world to increase your share value, can be met with jeers from your fellow stakeholders.

And then there’s the aforementioned alien technology. These are green cubes that are awarded to the players who explore alien worlds — and to be clear, I’m speaking about individual players rather than the companies they control. Alien tech can be traded for all sorts of benefits. Up to two cubes can be invested into a company to increase its shipping value, declawing the threat of rusting shuttles. Or they can invent wormhole technology to allow a company to warp across the map rather than paying for every intervening space. It’s even possible to upgrade your settled worlds, doubling their mining value, or launder them for cold hard cash.

The tradeoff, naturally, is significant. When the game concludes, the final value of everybody’s shares is calculated for one big payout. These are highly lucrative, the sum of a company’s shipping and mining values combined. But if a company that signed The Agreement failed to best the alien race on the mining track, their shares are directly claimed by the aliens — and pay out for a single measly credit instead of their usual value.

Frankly, this is a stroke of brilliance. The Agreement quickly becomes one of your most potent gambles, weapons, and looming threats all at once. The alien race is always on the move, ticking upward on the mining track at regular but unguessable increments. An over-leveraged shareholder might sign The Agreement for an infusion of cash that can be spent on more lucrative investments, or a tycoon might bet it all on a long shot. Either way, it provides high drama even in the later game.

Other elements lean into the game’s sci-fi setting, although with some squinting you can make out the railway ties. There are large “mega-earths” that welcome multiple companies and grow in value as they attract more investors, tax zones that encompass wealthier worlds but demand periodic payouts (i.e. dopey libertarian “state violence”), and, of course, the fact that a company might learn how to travel through stellar nebulae in order to bypass the competition.

Of course, the other side to this coin is that Stellar Ventures is denser and more complicated than most cube rails titles, not to mention it takes twice as long on the table. Personally, though, I find the whole thing energizing. Nilsson does more than blend genres; in some ways, he shores up the chinks in their armor. It always feels like there’s something squirrelly to get up to. Is a company not putting shares up for sale? Engage in some boardroom politics to force their hand. Even better if you aren’t the one to pick up the latest stock. When it sells for a pittance, you can smirk as your target corp shifts from privately-held to minor status, the value of each individual share diluting substantially. Oopsie. Did I just ruin your dividends for the foreseeable future? I’ll make it up to you by seizing a controlling interest in your other company.

Did I mention that Stellar Ventures is a game for vultures and rats? No? Okay: Stellar Ventures is a game for vultures and rats. And it rocks.

For the most part, anyway. I already mentioned the game’s phasiness and complexity and playtime. Personally, those are minor compared to the shenanigans it permits. As a game about putting cubes on hexes, it’s intriguing. But as a game about making half-understood treaties with technologically superior aliens, shafting your competitors with turn orders and negotiations alike, and not having to look at a single train engine, it’s unparalleled. Even if your shuttles keep rusting in the absence of oxygen or moisture.

Stellar Ventures launches on Kickstarter tomorrow.

A prototype copy of Stellar Ventures was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read about which films I watched in 2025, including some brief thoughts on each. That’s 44 movies! That’s a lot, unless you see, like, 45 or more movies in a year!)

Posted on January 26, 2026, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Stellar Ventures, TableTapas Games. Bookmark the permalink. 3 Comments.

I’ve been subscribed on BGG and Kickstarter to this game, more out of curiosity than anything. I’m glad it sounds good, it could serve as a good bridge between Cube Rails (which are a bit easier to get people into, being only slightly more rules complex than Ticket to Ride (if a lot more complex in player interaction)) and the off-putting 18xx that I can’t seem to table with anyone 😅. The theme probably helps with the extra complexity, in a kind of “spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down” way for most people. Me personally, I love a train game, I like the sparse aesthetic and relatable (if heavily abstracted) real world geographic maps. But…I’m not a majority of gamers and a lot of people I can get to play games of similar depth will eye a train game with scepticism, despite my protesting that everyone can enjoy a tran game regardless of interest in the theme.

Making a deal with some aliens to get cool tech is not just a fun twist to a well established formula, where the new innovation in a game is usually at the level that the shares pay out a bit differently or the round structure is tweaked a bit, or a map is especially hilly; it’s also a lot more immediately…”cool” (I put in quotes as it’s purely relative/subjective, but way more people would go “oh cool, alien tech” than “wow, there’s a slightly tweaked rule to constructing rail if you build it as a bridge across a lake”).

I may have to back this. The missus will be thrilled 😆

Thanks, I have a $ on this and am trying to decide if I can enjoy this experience despite the vultures and rats. I certainly have people I play with who would enjoy the shenanigans. I did back Lost Atlas because of the modular map tiles. It could be my second not quite square train like pseudo-business game and sit alongside Asian Tigers and Panamax in my collections small business game annex😁.

All the best.

Pingback: All Gold Country | SPACE-BIFF!