I’d Like to Lodge a Complaint

Ahh… do you smell that in the air? That winter nip? That hint of woodsmoke? It’s the tangy scent of preview season, baby!

First on the list is Peter McPherson’s Lodge. Ever wanted to design a lodge? Now you can. Sorta.

We’ve looked at a few of McPherson’s games over the years — Wormholes, Tiny Towns, and by far my favorite, Fit to Print — and Lodge fits right in as a cozy game about building an alpine retreat for winter sportists. Although if you know anything about my reception to two of those three titles, you might recognize that as a slightly barbed compliment.

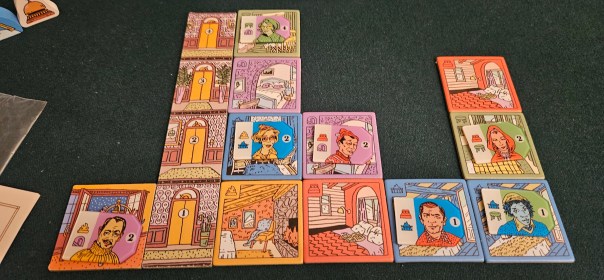

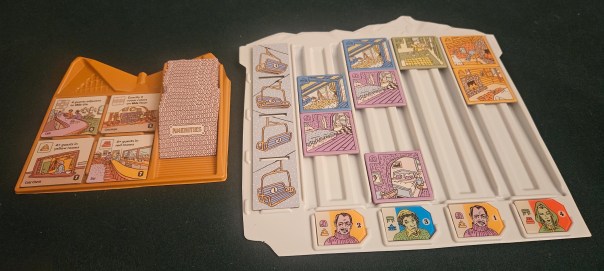

First, the basics. Your lodge, as befits all things built or assembled on a table, is presented as a tableau of distinct tiles. The way these are selected is downright clever, featuring a sliding board that shows sixteen offerings at first, only to gradually thin out as rooms are claimed and added to players’ chateaux. Only once an entire row of rooms has been claimed do you refill the thing, and rather than manually sliding each and every tile downward, you tip the entire tray onto its edge, transferring the admittedly minor labor over to our old master gravity. Snick, go the tiles as they reach the bottom of the tray. Satisfying.

The placement of those tiles is all-important, as you might imagine, but their location within the tray is more important than as a mere selection system. They’re also bound to a particular floor in your lodge. Any room on the bottom belongs to the ground floor, the next level goes on the second story, and so on until we reach the fourth and final level.

Furthermore, gravity plays a role in the construction process as well. As tempting as it might be to place a dangling room without anything underneath, sorry, but those aren’t the physical constants of the universe we currently inhabit. There goes my fantasy of building a lodge suspended by cables, Bond villain style, but the constraint works wonders for the actual gameplay. There’s real tension between expanding your lodge outward or upward, especially as the available rooms grow more limited.

Meanwhile, there are two additional objects to claim and place in your lodge, amenities and guests. Unfortunately, this is where Lodge begins to stumble.

Let’s start with amenities. In a nutshell, these are special rooms. Perhaps you’ll place a bar that awards extra points for housing guests in red rooms, or a gym that does the same but for purple-room people, or a concierge that only scores if its floor only includes two colors. First of all: Huh. I’m not sure what’s going on here. There’s a strong disconnect between an amenity’s real-world purpose and its gameplay effect, and Lodge doesn’t seem interested in bridging the gap. Second: Amenities don’t inhabit the usual sliding tray, instead occupying their own separate offer to the side. This sets them apart not only physically but also within the play-space. They exist in isolation, as long-shot bonuses rather than real considerations in their own right. The result is pretty much always a lodge that’s all housing and one laundry, or perhaps a lodge where the coat check is located three flights of stairs above the entryway, or a lodge with a hidden conference room right under the honeymoon suite. That’ll be fun for the annual carpet-steaming conference.

That same sense of disconnection extends to the guests. These are more important than amenities, functioning as both the game’s timer and its principal scoring method. Guests earn bonus points if they’re placed on the appropriate floor, which is fine. But they also demand to be housed in a specific color of room… that’s also adjacent to another specific color of room… which they will not occupy, but leave open for other guests to stay in, or even use as their own next-door-but-empty chamber.

On one level, this presents a perfectly interesting placement puzzle. Guests don’t care whether their adjoining rooms are adjacent on the same floor or located above/below their own, just so long as they share some timber between them. This forces players to think long-term, selecting rooms and guests opportunistically and always keeping an eye on the sliding room offer. It helps, too, that guests in higher floors earn more bonus points, but it’s tougher to quickly assemble the right rooms at elevation. That’s good stuff.

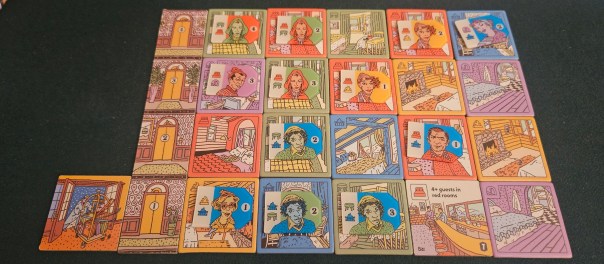

At the same time, these preferences make about as much sense as the amenities. Which is to say, none at all. Despite the warm illustrations by Leslie Herman, this quickly turns Lodge colder than it might have been otherwise. There’s just not that much personality behind any of your choices. Very quickly, a winning lodge becomes a mishmash of rooms, with no reason to prioritize one color over another, one type of guest over their peers, or the broader layout of the tableau before you.

It’s a shame in particular because the illustrations are lovely and the idea of assembling a prize-winning lodge is a tremendous one. But a lodge isn’t just an assemblage of rooms with maybe a single café in the middle. Is this a lodge for skiers that require laundromats and dryers? Or is it a lodge with day activities for bored spouses and cranky children? Or perhaps a lodge for glampers, all glammed-up tents with heaters sticking out the back, or a space for people who like the idea of winter sports but actually want to lounge around in the spa, or an all-inclusive hotel that happens to have snow around it? In Lodge, your lodge is none of those things. It’s really just a lot of color-coded boxes.

Which is to say, Lodge’s mechanical half lacks the sense of place it otherwise tries to evoke through imagery alone. It’s a far cry from the beachfronts of Santa Monica or the haunted houses of Scream Park. Where those games labored to connect the actions players undertook at the table with the way those spaces function in real life — complete with empty space, mismatched elements, and inhabitants — Lodge doesn’t come across as a lodge. Nothing speaks to its lodge-ness. The game could be a stack of Starbursts, with the guests a pack of children who prefer two particular flavors in proximity but will settle for one if they really must.

Again, the puzzle itself is good. It holds one’s attention. The tile selection system in particular is pleasant on the fingertips and asks the right questions about player priorities. Leslie Herman’s art is sumptuous.

But it isn’t so interesting that it couldn’t have striven to be more. For such gorgeous wallpaper, Lodge’s hallways are peeling at the edges. The result is a game that’s perfectly enjoyable, but lacks the ambition to stand out in a crowded field.

Lodge will be launching in crowdfunding next week. A prototype copy of Lodge was temporarily provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read about which films I watched in 2025, including some brief thoughts on each. That’s 44 movies! That’s a lot, unless you see, like, 45 or more movies in a year!)

Posted on January 22, 2026, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Lodge, PickPocket Games. Bookmark the permalink. 5 Comments.

Thanks for your honest assessment! Fit to Print is sooo good, but this looks like a pretty easy pass. Too bad, because with more theme to the choices I could have seen this going over well with some of my older kids.

I agree, Fit to Print is super.

Thanks for The Shining you gave to this upcoming Kickstarter. It tells me all I need to know about how it might all work and no play.

Darn it. All Work and No Play would have been such a good review title…

Dang it, that art is so awesome! I might’ve bought it for that alone.