Faith in Crisis/Transition/Expansion

Posted by Dan Thurot

It’s hard, maybe impossible, to not put yourself into Keep the Faith, the latest board game by Greg Loring-Albright. Going in, I always tell myself the same thing. This time, I say, the religion I create is going to be something different from the one I grew up in, the one I’ve spent a lifetime studying, the one that got me to learn a bunch of old languages in order to prove its connection to a millennia-gone church only to accidentally disavow itself in the process. And then, like this opening paragraph, somehow I find myself circling back, like a star trapped in a slow orbit around a black hole, hydrogen distending into that event horizon.

Okay, so perhaps I have feelings. Surely that’s a sign that Keep the Faith is a success. But if that’s so, then why is it so difficult to write about? Why has it taken me seven hours to get this far?

Keep the Faith opens with a new religion. (Already I want to quibble. Religions never begin at a concrete moment. Especially when they claim they do.) It begins with a series of values, six in all, arrayed like the spokes of a wagon wheel so that opposing traits are clearly delineated. Perhaps one of those values will be “Guard the Gates,” in which case its opposite value will be “Welcome the Outsider.” Or perhaps the dichotomy will be “Spread the Word” versus “Protect the Secrets.” Or “Be Set Apart” and “Be in the World.” “Recall the Old” and “Reveal the New.”

These aren’t contradictions, to my understanding, although someday this timeline’s New Atheists will insist that they are, probably with Power Point slides festooned with scary red arrows drawing attention to every self-rebutting verse. But that isn’t how I think about them, at least not necessarily, not always. They’re the creases and folds that occur whenever a human institution examines itself, points that aren’t in conflict, not even two sides of the same coin or two expressions of the same face, but varying applications of friction and heat and pressure.

Take Christianity. (Uh oh. Here we go. The black hole latches in its hooks.) Early in the religion’s life, after some emperor or another had declared a period of persecution that led many believers to lapse out of despair or convenience or terror, only for that same emperor to die a few years later and leave his dictates in the dustbin, believers were faced with an existential question. Should they welcome the lapsed back into the congregation or extract some display of contrition? And if so, what was that contrition’s proper severity? The lapsed had, after all, betrayed their faith and might pose a danger to the community. But forgiveness and long-suffering and turning the other cheek were essential traits of the faith. For one to deny a penitent their relief was to become oneself unfaithful. It was a pickle. But a contradiction? Eh. Ask the faithful. Ask the penitent. You might receive two very different answers.

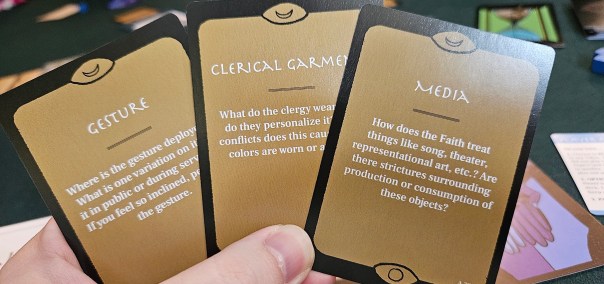

To these contrasting values, everyone at the table populates their nascent faith with a handful of aspects, always narrating the meaning behind each pairing. If I play the card that invites me to think about “Food,” I choose one of our values and explain how it’s reflected by this aspect. Recall the Old? That’s easy: our food is flatbread and bitter herbs, a reminder of our time in bondage. Accept Our Fate? That requires a little more thought. Perhaps we aren’t meant to think too hard about preparing our meals, instead taking what we can get as our religion expands to new continents and cultures. Shape Our Destiny? Food becomes an act of defiance, as prepared and dressed-up as possible. Eventually, we restrict ourselves to only the most enriched flours and mummifying preservatives, all the better to stave off the entropy that claims us all. Ironically, these highly processed meals shorten our lives. Is this a contradiction? I’m sure somebody has a Power Point for that.

This is the setup. But it’s also the play. Much of the time, Keep the Faith is about pairing aspects and values and then explaining their relevance. It’s also about shifting those aspects between values. At some point, maybe Food will be severed from Shape Our Destiny and move over to Wielding Power. We narrate the change: somebody has persuaded their coreligionists that the former use of food was a contradiction; now it’s a sign of dominance. The wealthy eat everything while everybody else fights over the scraps.

(Again, the black hole pulls at me. We’ve reinvented trickle-down economics and the fabled Needle Gate of Jerusalem and every other false justification of the wealthy that they deserve not only to eat well, but also the untouched extras as well. Is my brain the trap here, or is humanity bound to a turning wheel from which it will never quite wriggle free?)

These aspects are presented without oversight from Loring-Albright. Like the ecclesiastical positions of Amabel Holland’s Nicaea, there are no icons stating that one aspect is more valuable than another, or even valuable in a distinct way, or that there are resources tied to these concepts of Media and Social Conformity and Hierarchy and Esotericism and everything else. They are offered as blank slates. (No. Not quite blank. Because, again, there’s no escaping the black hole, no breaking free of the wheel. It’s just that their value isn’t encoded within the game’s rules. Instead, it’s encoded within us, the players.)

At multiple junctures, every time I play Keep the Faith, I balk at this blankness just as I balk at my incapacity to frame the game’s nouns in a novel way. I have my own hangups with role-playing games, and I grow frustrated when board games are presented as imaginatively inferior to their more improvisational cousins. In one sense, the absence of a stance — that “Animals” and “Gender” and “Ancestors” are presented as equivalents within the game’s ludic rhetoric — strikes me as a dereliction of duty on Loring-Albright’s part. It’s a thought I always shake off, but before long it sneaks back in again. If we, the players, aren’t willing to share some part of ourselves whenever we pair an aspect to a value, the cards might as well be blank. Physically blank, not only blank of icons.

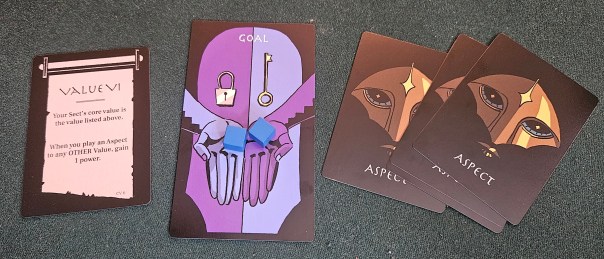

However, there is a governing logic behind these assignations. While the moment-to-moment gameplay depends entirely on the players’ willingness to narrate their choices, there is an underlying drive. When the game begins, we receive a core value that our particular sect holds dear. Maybe I care most about Recalling the Old, while you’re all about Welcoming the Outsider.

But we also each receive a hidden goal. Perhaps I’m Righteous, in which case I want to protect my core value at all costs. We will Recall the Old, forging a religion of calendars and feasts and constant observances. In game terms, this translates to me keeping as many aspect cards tucked under my core value as possible. But in that same session, you might be Steadfast. Even if it means abandoning your core value, you intend to achieve stability in our faith, ensuring that one half of the wheel is filled with as many aspects as possible.

What’s interesting is that these objectives can be entirely complementary. There’s a world where my single-minded zeal and your spineless centrism go hand in hand. But what if one of our co-players is Rebellious? Their goal is to slap as many aspects onto non-dominant values as possible, driving our faith into a period of schism. These objectives push Keep the Faith into more familiar territory, games-wise, but make no mistake, they function foremost as narrative devices. Every round, the clock shifts forward. A century passes, some new question or crisis arises, and the landscape of our faith shifts out from under our feet. Our overall goal remains firm — unless we opt to alter it, a possibility provided by the game — but our sect’s relationship to its core beliefs is always in flux. (Of course, there’s no such thing as a community that maintains exactly the same values over centuries. Today’s rebellion becomes tomorrow’s centrists, as they say. But like every other parenthetical in this review, this isn’t a critique as such, just a note.)

If you couldn’t tell, I’ve had a complicated response to Keep the Faith.

As a board game, it’s rather plain. The entire thing lasts maybe an hour and a half, give or take a few minutes depending how stridently people decide to chase their individual objectives. I mentally sort it into the same box as Jenna Felli’s deduction games, especially Bemused, where the incentives are opaque enough that newcomers are often left unsure of what they’re actually meant to do here. One can attempt deduction, trying to suss out what their fellow players hope to accomplish, but those energies are better spent elsewhere. At root, it’s about shifting stacks of cards from one place to another; beyond that, there simply isn’t enough scaffolding to produce much in the way of classic gameplay.

As a role-playing experience, it suffers from the same problems that harry other RPGs with heavy topics on their mind — namely, that everybody brings their own expectations to the table and must navigate the collaborative process to the best of their abilities, and even one awkward or uncomfortable moment can turn the whole thing to rubble. This is also, naturally, the game’s strength, provided everyone agrees on some ground rules. It can be funny, sad, traumatic, cringey, or dramatic. Sometimes it is all of those things within the same few minutes. Because the tale it tells is more institutional than personal, it also encourages a certain distance from its subject matter. Given its closeness to so many lived experiences, this is a huge relief.

As a historiographical toolkit, it’s without parallel. Just flipping through the cards is a useful exercise, demonstrating how faith and religion can intersect with things both large and benign. One card is titled “Prophets & Gadflies,” emphasizing the highest and lowest reaches of its cultural landscape. But that’s an obvious example. One is invited to consider symbolism, clothing, gestures, plants, sacrifices, figures of speech, weather and seasons, music, language, beverages, gifts, and so much more. Where modern study tends to put religion in a box, Keep the Faith breaks it out again. I would recommend it to students of religion in a heartbeat.

As a personal experience, it splits some raw nerves. I expect I won’t be alone in that. My own faith tradition, Mormonism, argues that it is a direct descendant of Christianity as it appeared in the first and second centuries, before the Catholics and Romans came in to mess it up. It’s an argument that’s made by pretty much every Christian sect. We are the original. Our values are Jesus’s values. These practices are pure and untainted by the world. Never mind that our own practices and values have changed within lived memory, let alone the centuries.

Keep the Faith puts such a sadness in me. Because it’s hard, maybe impossible, to not bring myself into this thing. It’s impossible to not see the kid who fled into religion because of abuse, even when that religion was also the cause of the abuse. It’s impossible to not see the idealist missionary who was let down by the institution. It’s impossible to not see the young scholar, learning that everything he had been taught was an excuse rather than good information.

That’s healthy, in its own way. (Yes, it is.) But it hurts, too. (Yes, it does.) If I had to stamp my own thesis on the experience, I would say that Keep the Faith is about how religion is every bit as contingent and changeable as every other human creation, but that, paradoxically, it displays one true constant in its overriding need to always pretend it has always been this way, to chart its roots to the beginning even as it’s constantly born anew, to insist that it honors its heritage even as it spills buckets of whiteout and ink across its own pages. The result is a complicated, textured experience, one I intend to use in the classroom but will probably avoid for personal consumption. Along the way, the wheel keeps turning, the black hole keeps pulling me inward, and the faith keeps being kept. Here is the note of hope and the note of despair, hand in hand: It will change. And then it will pretend it never did.

A complimentary copy of Keep the Faith was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read about which films I watched in 2025, including some brief thoughts on each. That’s 44 movies! That’s a lot, unless you see, like, 45 or more movies in a year!)

Posted on January 13, 2026, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Central Michigan University Press, Keep the Faith, Role-Playing Games. Bookmark the permalink. 6 Comments.

Wow! Another one of your really thoughtful and thought-provoking reviews. Thank you for the mental and emotional stimulation!

Thanks for reading!

Wow! Thank you for this.

I think you’ve really captured the paradoxes of faith here, especially in that last paragraph.

I was initially a bit hesitant to use that type of terminology, in case it came across as being too “Christianity coded”, but that isn’t the intent, and from within my own limited world view I couldn’t think of a better way to describe it.

I personally think there’s something universal in the search for meaning and belonging, and for those who genuinely try to engage with it, wrestle with it, and be honest with themselves, regardless of religious affiliation or purposeful distance from the same they will run into these struggles with ideas and themes that are and aren’t contradictions. Again my personal bias is showing, but I think it’s this process that makes us better humans.

So once again thanks for a candid and well written piece.

Thanks for reading!

Is this the first board (though this feels more like an indie TTRPG, or “story-games” as the most used forum for them was called for about a decade), published by a university?

No. Although the others I’ve heard about also come from CMU Press.