A Rather Whistful War

Fred Serval, one of wargaming’s great rabble-rousers, has a new game out. It might not sound like a new game, since I covered it a year and a halfish ago, but that was a convention freebie that required scissors and some buttons from your bottom drawer to play. A Very Civil Whist is now an actual game you can buy and play and push around, or maybe even press into service as a doorstop if that’s your thing.

I like it even more now than I did the first time.

Even as an exercise in minimalism and design limitation, A Very Civil Whist is quite the thing to behold. Like the original one-sheet version, the game is largely playable with a single deck of cards that fulfills four different purposes at the same time. There’s an actual map board now, plus chunky cardboard counters for everything, and some chess pieces for tracking the fronts and foreign support in its ongoing English Civil War, but the highlight is still that deck of cards.

As you can probably tell from the game’s title, this is a trick-taker, although there are some wrinkles that prevent it from feeling too much like anything else out there. Like German Whist, there’s a drafting phase, in which both players deploy a small hand of cards in order to secure other cards, and some combination of your original hand and those later additions then serve as your tools for the battles, domestic and foreign support, and reactions to come.

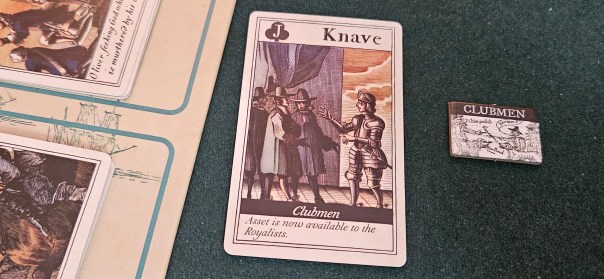

The deck is really something, both visually, thanks to the old woodblock prints that are their illustrations, and as a mechanical showcase. Most of the time, only the 4-9s get used in the trick-taking, tightening the scope in a way that’s even easier on card-counting, or at least card-vibing, than the form usually permits. The 10s serve as power-ups that unlock when your faction reaches a certain threshold: securing enough foreign support as the Royalists, say, or seizing some good ground in the northern war as Parliament. This basically confers an insta-win in that particular suit, although of course one should be suspicious of anything that seems like a sure strategy.

The remainder of the cards still matter. The lower suits, those 1s through 3s, function as a casualty check. When an attack fails, you draw a pair from this deck and see whether they sum to a higher number than your commander’s resilience; if so, he atones for his dishonor by falling on the field of battle. This is, to put it lightly, a bummer, especially when one of your better leaders bites it early. In one of my more bruising sessions, I managed to bring out Oliver Cromwell only to watch as he tripped onto his own sword in his very first fight. Let’s call that a good outcome for the Irish Catholics.

Meanwhile, the face cards become events. A Very Civil Whist is a brisk game, only four hands long at maximum, which requires two events per round. But they’re high-impact things, not to mention load-bearing tendons in the game’s connective tissue. Queen Henrietta might appear to call upon a burst of foreign support from her home country, or new counters might enter play to provide a one-time boost to your odds in battle. My least-favorite event — and I mean that in the complimentary sense — is the one that allows Parliament to examine every pair of that round’s drafted cards in advance before hiding one of them face-down, turning the draft into a nasty bluffing minigame.

With the cards pulling so many duties, it may not seem like there’s enough to keep players engaged. Nothing could be further from the truth. A Very Civil Whist is nasty, brutish, and short, all qualities Serval leverages to the game’s benefit. The military fronts are seesaws, their tracks kin to States of Siege’s lanes, always under threat. Shoring up your domestic support is necessary to declare victory, but requires players to discard their most precious cards. Unlike some trick-takers, there is never a moment that feels foreordained; there’s always something to do, some weaselly advantage to be clawed over on your rival.

Which brings us to a larger question: is A Very Civil Whist worthwhile as more than a plaything? As a trick-taker, it’s very good. As a visual production, it look fantastic. But what about as an expression of its historical conflict? We are, presumably, interested in these games as portrayals of their conflicts, not merely as vague nods in their direction.

There will be some variance here. Between its approach to events and the way its verbs relate to its card-play, there’s no denying that this occupies the far end of the CDG wargaming spectrum. In other words, it’s profoundly abstract. With some imagination, one may imagine the cards as stand-ins for broader considerations: some diplomatic tact here, the New Model Army there. But I doubt anybody would argue it doesn’t require the aforementioned imagining.

Where A Very Civil Whist excels, I think, has less to do with the invocation of specific occurrences, and more to do with the closeness and acrimony of its conflict. One doesn’t gain a sense for the progression of the English Civil War so much as for its unprecedented and brutal nature. Like the term “civil war,” the game’s title is a bitter irony. There is nothing civil about it. The war’s actors may speak the same tongue, may wear the clothes of noblemen, may speak in lofty dialogue. But here they are, grubbing in the mud for advantage over their closest peers. Nobody will emerge from the game any closer to having memorized the war’s important dates or understood its underlying causes. But they may grasp some of its proximity, some flicker of the reverberations it will send down the centuries. This is the true starting point for the Age of Revolution. Some may mark its date later, up to a full century after these events. But, no, it is here, in these very English debates over the ultimate source of sovereignty, over which taxes are justly imposed and which are unfairly extorted, over questions of which kingdoms should be accepted to rule over others, over the framework of constitutions and who deserves to benefit from them, that the great upheavals mark their beginning.

In any case, it’s hard not to be drawn to A Very Civil Whist’s sheer audacity. It’s a single-deck game that prizes playing cards for their versatility as much as for their ubiquity, and deploys both traits to great effect. It’s a hybrid of trick-taking and wargame that manages to emphasize the strength of both forms even as it forges its own identity. It’s even another investigation of revolutionary history, making it the rightful partner of A Gest of Robin Hood and Red Flag Over Paris — and, in many ways, their superior.

A complimentary copy of A Very Civil Whist was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read about which films I watched in 2025, including some brief thoughts on each. That’s 44 movies! That’s a lot, unless you see, like, 45 or more movies in a year!)

Posted on January 9, 2026, in Board Game and tagged A Very Civil Whist, Board Games, Fred Serval, PHALANX. Bookmark the permalink. 10 Comments.

I had the chance to play this at PAXU and have been eagerly waiting for its release. I’m not very familiar with the history behind the game, but I found the gameplay captivating.

Hey, that’s one of the nice things about games like these — they provide easy entry points for learning some history!

I was truly shocked by how much fun this game is. As someone with similar ideologies I have always sought to support Fred’s work, but this is by far my favourite of his titles so far.

Right! That’s one of the things I’m trying to get across here. It isn’t only good or interesting as a trick-taking hybrid — it’s genuinely enjoyable and exciting.

I saw 191 movies in 2025. But, I can’t imagine even my closest friends sitting through my brief thoughts on every one of them. So, by comparison, 44 sounds like a very civil amount of movies to read someone’s thoughts on.

Wow, that’s (counts on fingers) a lot more than I saw! Was that all new movies or repeats? I guess I didn’t count repeats, but even with those I doubt I broke 100.

102 new, 89 previously seen 🙂

Wowza! Well done!

Any suggestions on favourite trick takers of late, or ones you’ve gravitated to more and more? Just got into Wizard and would love any insight or suggestions!

Hm, that’s a toughie. From the last year, I really enjoyed We Need to Talk and The Hedgehog’s Dilemma, but both might be tough to find. Also This Is Not a Game About a Pipe, but that one has been nuked from orbit for copyright violation.