Joy in the Burnout

Eric Dittmore’s Adulting is not Johnny O’Neal’s Adulthood, although it’s inevitable I’ll mix up the two titles somewhere in the text of this review. In fact, I already have! Twice! Once in the permalink and again in the tags! It happened about ten seconds apart, and after the first time I even reminded myself to never do it again.

In a way, though, that’s about as strong a metaphor for Adulthood — dammit, Adulting — as one could hope for. This is another forthcoming Indie Games Night Market title, and it might be the strongest of the year’s batch, in no small part for how well it represents the challenges of daily adult life.

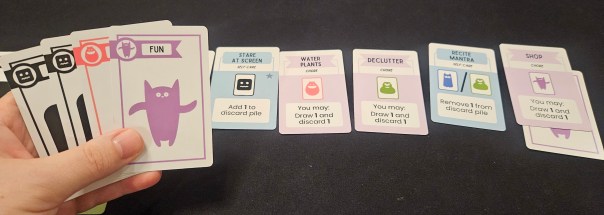

Set over the course of a single weekend, Adulting presents itself as a deck-builder in fast-forward. Your starting deck is filled with the customary ten cards. Six of those cards are labeled “stress,” representing the anxiety-ridden nerves that can’t tear themselves away from the latest doomscroll. The other four are your attitudes: productivity, chill, fun, and caring. The things you hope define you, and sometimes maybe even do.

Even in its earliest moments, Adulting presents its goal as multilayered. At the basal level, you want to get through the weekend without depleting the extra stress cards in the market. This is done by completing chores, tasks like vacuuming, shopping, and watering your plants. Completing a chore is simple enough. Spend the right card, or any two of the wrong cards, and you’ll get ‘er done. But chores reset every day. And additional chores spring up each morning. And leaving them undone piles up more stress. If the market runs out of stress cards, the game ends in ignominious burnout. You know, like 99% of board game review channels. We’re fighting for our lives out here.

But that’s only the first of the game’s layers. There’s also self-care to consider. These cards are not unlike chores in function. Once added to your tableau, you spend cards to activate them. Their effects are varied. Some add new attitudes to your deck. Others let you draw cards, or move cards around, or maybe remove a pesky card entirely. At the end of the day, any self-care activities that weren’t undertaken will disappear from your timeline.

Which isn’t the end of the world, all things considered. Except your secondary objective is to complete the game with at least as many self-cares as there are stress cards in your deck. Adulting isn’t only about accomplishment. It’s about the reasons behind the chores. The good stuff. The rich life.

Finally, there’s your ideal self. Drawn at the start of the game, this is your personal objective. Provided you don’t burn out, and provided you manage your stress, it’s time to evaluate whether you’ve inched closer to the person your younger self believed you would inevitably become. Depending on the card, these goals vary. Some are all about accumulating a certain number of cards. Others require you to minimize your stress, stay on top of every last chore, or even outperform the other members of your family. I laughed out loud when I drew the “freeloader” objective. Their goal? Have fewer chores than anybody else.

To be clear, Dittmore doesn’t offer a firm stance on which level constitutes “victory.” It would be nice to cover every task, strip your deck down to nothing but good vibes, and reveal that you’ve pupated into your rock star persona. But, real talk, that isn’t likely.

For one thing, Adulting isn’t quite a cooperative game, even though it sometimes plays that way. Anyone can nab an unclaimed chore, and it’s even possible to take other players’ responsibilities from their routine, covering tasks someone else at the table lacks the spoons for. But it’s also possible to swipe other players’ self-care cards. Or to pursue your own interests no matter how much stress a family member is absorbing. Which isn’t to say that the game is semi-cooperative, either! Most of the time, there’s a collaborative atmosphere at the table, especially when a bad draw sees one player falling behind.

Rather, Adulting occupies the rare category of “multi-victor” game. It’s up to you to determine whether you won or lost. Far from making the experience feel undirected, this provides clarity. Like actual life, Adulting is sometimes about thriving, and sometimes it’s about scraping by. We’ve all had those days. I mean, burnout seems like a clear loss to me. But that says more about me than anything, because, look, some weekends, getting through the chores deserves a platinum trophy.

What I appreciate most about Dittmore’s laissez-faire approach to victory conditions is that it sidesteps the stickiness that pervades other games about adulthood. We could call it The Game of Life problem, but it runs deeper than that. To offer a contemporary example, in Adulthood — and I’m really talking about Adulthood here, not Adulting — I recoiled somewhat from how the game narrowed its scope to particular experiences and particular methods for evaluating those experiences. To put it bluntly, it’s weird to assign a score to a person’s life. No matter how many apps and pedometers and gamified gym memberships we normalize, I prefer to think of a human being as ineffable and valuable. Even when someone is in the middle of crashing out. Especially then.

Adulting avoids that problem entirely. Sure, its scope remains constrained by necessity. There’s no hard mode wherein the player struggles with children or a disability, nor can your weekend be intruded upon by a geyser of food poisoning. But its presentation is more or less universal, at least for those of us who vacuum our own floors.

In that sense, as well as for its tight temporal scope, its humanity, its griping about our material conditions, it recalls Jon du Bois’s Heading Forward. Adulting is the lighter game by a mile, easy to play and joyously fluid. Unlike most deck-builders, for instance, your hand is an ever-shifting thing, cards revolving in and out on the regular. Every morning you draw five cards, but it isn’t uncommon to cycle through twice that number or more by nightfall.

It’s an excellent game, in other words, even when it speaks to Something Bigger. Its ambiguous social space is a crucial part of that. Can you rely on the people sitting beside you, or are they determined to play the freeloader? If so, is that necessarily worse than living with a perfectionist? Is there room for compromise? These questions come up on their own. Or not! It doesn’t ruin the experience either way. That’s how flexible Adulting is.

Playing indie games, sometimes there’s an attitude that we need to “go easy.” Maybe these things haven’t had the advantage of robust playtesting. Maybe they lack stellar art direction. Maybe their designers are still developing the muscles necessary for crafting their masterpiece.

Adulting is wonderful. Not only for an indie game. Not only for a self-published production. Just wonderful, full stop. For a freshman designer, Dittmore demonstrates a confident hand. The cardplay is simple but thoughtful. The challenge is present but not overwhelming. It even does the multi-victor, self-defined-success thing without once feeling like a cop-out.

Yes, it helps too that Adulting holds up a mirror to our own busy lives. It’s telling in little ways. The “stare at screen” card. The stolen moments of joy amid the bustle. The relief of a helping hand from somebody sitting beside us. What a warm, inviting, comforting game. It has already become one of my self-cares.

A complimentary copy of Adulting was provided by the designer.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, you can read my third-quarter update on all things Biff!)

Posted on November 6, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Adulting, Board Games, Indie Games Night Market. Bookmark the permalink. 3 Comments.

eric is awesome and adulting is a lot of fun. the idea that we each decide for ourselves what constitutes a victory in the game and in our lives makes the game feel special, relevant, and relevant. i enjoyed your review of this wonderful game

Thanks for reading, Michael!

Pingback: Best Week 2025! The D.T.R.! | SPACE-BIFF!