Almost Famous

I know what it’s like to be scooped. Years before I could write The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner got to it. It’s doubly unfair because I wasn’t even born yet. That’s why I’ve vowed to cover any board game that seems like it’s riding the coattails of a more popular title.

For example, Famous: Stage I, the build-a-band game by Jared Lutes, might seem like a knockoff of Jackie Fox’s Rock Hard: 1977, but it would be a mistake to confuse their proximity for inspiration. Famous, it turns out, is the more tangled game, messy like a rocker who’s stayed up too late penning songs and doing drugs. Sorry, candy.

My objective today is to talk about Famous without drawing too many comparisons to Rock Hard. I know, I know, this challenge is difficulty level: impossible. But in this case it’s warranted, if only because Famous approaches the concept from such a different angle.

To be clear, there are plenty of parallels. Like Fox’s semi-autobiographical title, Lutes zeroes in on a handful of the same elements. Rounds are structured around discrete blocks of time, in this case weeks, and while Lutes doesn’t use worker placement the way Fox did, the emphasis is still on how your up-and-comer will prioritize their daylight. Each week affords fifteen hours of free time. These precious hours must be spent on things like writing songs, practicing with your band, building hype, and making industry connections. The portrayal here could be considered sloppier than Fox’s portrayal, especially when it comes to things like booking gigs or recording your freshman album, both of which are disconnected from the core action economy. But there’s something to be said for the unkempt among us. Famous is a mess. I’ve been led to understand that so are many of our best musicians.

This does make for one rather stark irony. For such a clean game, development-wise, Rock Hard was largely about the messiness of its rockers’ lives. Your day job jostled for attention with your band. Spending the night on the town was as essential as playing Yenser Stadium. Consuming hard drugs was the best way to stay abreast of the many demands on your time. Even the money seemed grungy and swiftly disappeared into your manager’s back pocket. I criticized Rock Hard at the time for veiling its harsher aspects behind the candy metaphor. When it comes to Famous, the musicians are squeakier than the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. The distractions are inefficiency, not self-immolation.

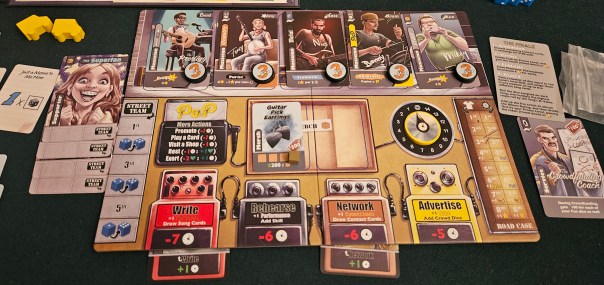

Famous carves out its own identity by focusing on the nitty-gritty. When the game opens, your band consists of a sole member, whether a prodigy whose uniqueness translates into some breezy fame, a fashionista who effortlessly finds all the hottest gear, a virtuoso whose skill is undeniable, or some other member of the game’s colorful cast. Over time, other musicians will enter the fold. In my most recent session, my pop band was staffed by a banjoist who preferred country music, a heavy metal bassist, and an ocarina player who could play every theme from every Zelda game.

Band members earn bonuses when slotted into the right flavor of group, although you’re more likely to take what you can get thanks to the clutter that defines the system. That’s because they’re drawn from the same pool that’s also crowded with the coders and superfans who manage your street team, publicists and agents who confer benefits for a one-time fee, prospects for earning various bonuses and private gigs for avoiding the rat race that defines the more public bookings. These elements are all essential in their own way, and they’re all jumbled together. It’s possible to increase how many cards you draw at a pop, just as it’s possible to increase which deck of song cards you compose from and whether you earn lifelong fans when you put on a good show. But in the game’s early stages when you desperately need to bump up your skill to play better venues than the local watering hole, you’re looking for warm bodies who can hold their own on the kazoo.

On the one hand, this turns Famous into something of a grab-bag. Finding the right bandmates, those who not only perform the same music as your lead, but also offer worthwhile long-term goals, is chancier than hustling bingo at a retirement home. On the other hand, this riddles the entire experience with a make-do attitude. You’re visiting thrift shops for secondhand amps and feathered jackets. Your steadiest gig is the Cracker Barrel parking lot. You’re peddling swag out of your van, and some of the better items include guitar pick earrings and branded baby onesies. The whole thing feels scrappy. Success is not foreordained.

That same atmosphere extends to the actual gigs. Booking is as close to worker placement as Famous gets, positioning vans on the board and then hyping up the show to increase your audience. The stand-in here is dice, sometimes entire heaps of the things, which must be rolled against the gig to determine a whole range of factors. How much money you take home. Whether you sell merch. How much closer to fame you’ve inched. Whether you transform one of those drab blue dice into a golden fan that can be reused regularly. It’s possible to bomb on stage, although the right preparations can mitigate an outright disaster, turning each show into an elongated press-your-luck game.

To be clear, while some of these elements emphasize the disjointed nature of a band’s earliest stages, others venture into the slipshod. Many actions could have been assigned simultaneously, so little impact do they have on your competitors. Others, like shopping, are presented as minor races to secure the best outfits and gear. Even booking gigs depends on turn order, rather than something driven by the players. It’s here that Rock Hard’s comparative polish really shines, making Famous feel a little auto-tuned by comparison.

Take, for instance, the way songs are composed and your freshman album is pressed. The songs are a matter of drawing at random from one of two decks, revealing pieces of music that may be worth more or fewer points in the endgame. Apart from some “funny” track titles, that’s it — no icon-hunting, no synergies with your band, nada.

That endgame, meanwhile, treats players to a final roll-off, everybody assigning dice to their five best songs and then rolling to determine those songs’ multipliers. Oh, and then your album value is divided by your promo level to produce actual points. The whole process is an odd match for what Famous achieves elsewhere, cranking the dial from the scrappy tableau-builder end of the spectrum to the weird euro math side. Instead of going to eleven, it goes to ninety-three divided by six, plus the aspirations of your band members, and then the formula repeats for your remaining cash.

The solitaire mode is a little more interesting, presenting a series of milestones that can be met, although here, again, the reward is a lower divisor to your final score. In both cases, Famous disappears down the wrong rabbit hole.

Which isn’t to say the experience is ruined. Famous is disjointed and underbaked, but it’s compelling in its own right. There’s real pleasure to be found in nailing a gig, in earning some ride-or-die fans, in completing the right ensemble for your persona. It’s just that Famous can write, but it hasn’t bothered to edit. The game lasts nearly three hours, which is quite the sitting for a game that relies so heavily on draws from the deck and rolls of the dice. There’s a great dice-rolling game in there, rubbing elbows with a great tableau-builder, crammed into an elevator with a really sharp management sim. Added together, and with so little attention paid to any given element, they’re less than the sum of their parts.

In the end, Famous: Stage I replicates the early stages of a band’s career perhaps too well. It’s messy, discordant, and has yet to find its voice. For what it’s worth, I do hope Lutes gives us Stage II. I would love to see the hustle years, the experimental phase, the breakup. I want to see these goofballs tour. I want my ocarina player to introduce a homewrecker to the mix. I want someone to develop a sugar addiction. I want the comeback tour in our sixties, the lawsuits against our manager, the commercial jingles.

Until then, Famous reminds me of that college video of MGMT playing “Kids” on campus in ’03. The video is grainy, the sound mixing is off, their voices are uncertain. There’s a banger under all that noise. Someday, I’d like to hear it.

A complimentary copy of Famous: Stage I was provided by the designer.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my next essay, on the competing strands of history and criticism that are present in my work. That’s right, it’s the Death of the Author, bay-bee!)

Posted on October 2, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Electric Lute, Famous: Stage I. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0