Kinfire Homeowners Association

Kinfire Council is full of jolting moments where I can’t tell whether Kevin Wilson wants to Say Something or I’m just suffering from a momentary case of pareidolia. As councilmembers of the once-great city of Din’Lux, we’re treading water while the world goes to hell. Magical climate change has led to sweeping food insecurity. Cultists are tearing down the very safeguards that have seen them prosper. Our politicians are feckless cowards who will swap sides the instant it seems expedient. Oh no. Is this the United States of Din’Lux?

More like the Homeowners Association of Din’Lux. After the events of Kinfire Chronicles and Kinfire Delve (all three of them), we’re patching the city back together one brick at a time. Most of our activities are suitable to such a task: gathering taxes, delivering food, deploying seekers with magical lanterns to kill the monsters in the sewers. Others make less sense. Can we censure the councilwoman who regularly visits the pub to court the evil cult’s loyalties? No? Hmph. Semi-cooperative once again proves the shakiest mode for any designer, even one as experienced as Wilson.

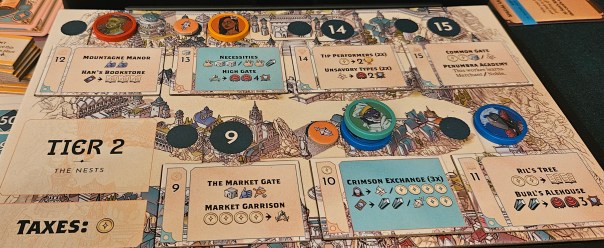

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, it’s useful to set the scene. Din’Lux is built on the coast of some fantasy realm, surrounded by a tide of “Starless Nights” that mutate man and beast alike. Its three tiers speak to some nasty class divisions, or they would if we, the city’s highest ranking officials, didn’t have to pay taxes to access the essential infrastructure in the upper levels. Oh well. That’s gameplay for you.

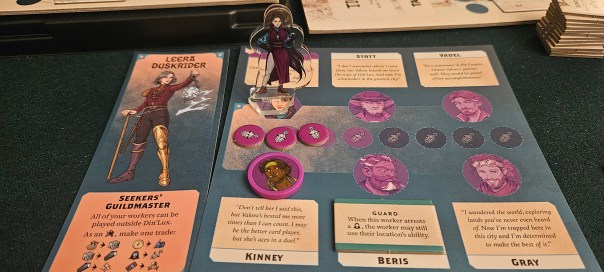

With its many sectors and underlying corruption, Din’Lux demands comparison to Lords of Waterdeep, the now-ancient (in game years) title that popularized worker placement and starkly divided hobbyists between those who called its pieces “wizards” and those who called them “purple cubes.” As with the rest of the Kinfire titles, Kinfire Council’s greatest strength lies in its sense of place. Your workers are actual people, with little portraits and character blurbs. With some time and training, they might even develop specializations. Training a worker to be a scholar lets you draw cards instead of taking resources, while guards are suited to arresting cultists and nobles don’t pay taxes. (There’s our class commentary.) Everyone will still call them workers rather than insisting on dubbing them “Jayde” and “Vella,” and it isn’t as though your functionaries will ever refuse a job, but it’s a nice gesture toward the idea that these are people with ambitions and lived experiences.

Your final worker, meanwhile, is a seeker. These familiar faces were the protagonists of Chronicles and Delve, here repurposed to perform the councilmembers’ dirty work. These are the only characters who can travel safely beyond the glow of Din’Lux’s protective lighthouse, which means they’re the ones you’ll send to far-off towns, where annex lighthouses are being constructed and lit, or perform the monster-slaying inherent to carrying a magical lantern on one’s hip. Their placement on the map always represents a minor crescendo, and, as someone who feels that Delve is the high point of Wilson’s Din’Lux universe, I’ll confess to being tickled pink every time I send Valora or Roland to tackle some quest that’s hit my table in another of these titles.

The actual worker placement, meanwhile, is handled in workmanlike fashion, with the wrinkle that it resembles a drinking fountain under firehose pressure. Din’Lux is absolutely sprawling compared to most of its genre peers. Not only are there quite a few spaces to consider — eighteen in the city proper, plus up to five spaces outside for your seekers to tackle — but most spaces also offer two separate possibilities. Making this clutter even more intimidating, the city is crammed with icons, necessitating a double-sided reference card for the near-sighted among us, but the game only provides two of the things even though it plays with up to six people. Hope you’re comfortable sharing.

Fortunately, most spaces are simple enough that they become, if not second nature, at least quick to internalize. There’s sufficient room in Din’Lux for multiple approaches to most problems. To give a simple example, you might want to provide food to the starving masses. To do so, you could send one of your workers to help on a nearby farm, spend a day aboard a fishing vessel, or mosey through the boardwalk market. And those are just the offerings from the free bottom tier. Heading into the city’s upper levels requires you to spend either one or two coins as an entrance fee, but yields more powerful actions and rarer materials.

Given the game’s apocalyptic gauze, these resources are suitably pinched. It’s uncommon to hold much of a surplus unless you’re preparing a seeker to dispel a pressing crisis, and even common resources like food or coins can scrape the barrel as you struggle to make ends meet. There are cards that provide special abilities, because of course there are, creating little arms races as councilmembers churn the deck to obtain the best offerings. These cards vary so wildly in their effects that they’re frustrating as often as they are exciting, especially in a game that’s otherwise so tightly leashed, but perhaps they serve as a worthwhile harbinger of the loosey-goosey social gameplay that soon emerges.

Speaking of loose gooses, it’s time to talk cults.

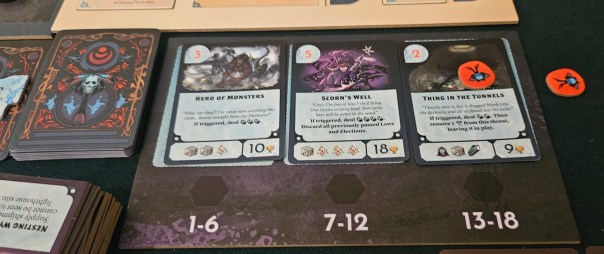

Din’Lux is utterly lousy with cultists. At the start of every round, you draw a handful of chits from a bag. As a selection mechanic, it’s redolent of the initiative system from Kinfire Chronicles, here determining which districts of the city the cult occupies and the crisis cards they draw. Cultists block spaces, which is bad, but can be arrested and turned in for bounties, which is good. The crises they engender, on the other hand, stick around until somebody amasses the right cache of resources to send a seeker to deal with the problem, and in the meantime might spark riots or tear down one of your expansion lighthouses. This is bad for the city, increasing the cult’s score alongside everybody else’s.

There are ample ways for the cult to tweak their score. Damage to lighthouses, city needs that went unmet, and so forth. When the session concludes, their score leaps upward thanks to the face-down crises that were seeded during setup, plus any others added to their stack as the game progressed. It’s entirely possible that the cult will outscore everyone else, ostensibly plunging Din’Lux into despair and mutation. Arms for antlers, eyeballs in armpits, that sort of thing.

But this is where Kinfire Council starts to tinker with semi-cooperation. When the game begins, the entire city council is allied against the cult’s machinations. For good reason, too, since opposing the cult is usually the easiest way to boost your score. Delivering food scores a couple points, helping a town construct a lighthouse might be worth a half-dozen, but slaying a herd of monsters or clearing a cultist’s den could net ten or eighteen. Of course, these quests require preparation, not to mention the attendance of your seeker. Still, that’s favorable math.

Until the cult starts to accomplish its goals, that is. As new cards are added to the cult’s scoring pile, the city council starts to look like rats on a fireworks barge. Rather than spending your coins and crystals on helpful things like killing monsters, it begins to look smarter to turn them over to the cult to increase your standing. In effect, you’re betting on the cult’s success. Your own score is now immaterial. If the cult wins, you win. Just, you know, with eyeballs in your armpits.

Frankly, this system doesn’t work, at least not in any meaningful way. It’s possible to swipe the win by joining the cult, sure. But it never comes across as a decision that necessitates much deliberation. Either the table does a great job of suppressing the cult or they don’t; despite the variance of points, it isn’t that hard to sense which way the wind is blowing. If anything, there’s no reason not to dump a point or two into the cult at the last moment.

To be clear, standing with the cult requires some sacrifice, using up one of your rare lantern tokens. But lanterns diminish in usefulness as the game progresses, especially in its final round when the voting system — itself underdeveloped — more or less stops mattering. And there’s no pushback to hobnobbing in known cult taverns. Your rivals on the council can’t censure you. The muckety-mucks in the upper city won’t bar you from their shops. Your seeker, who has spent quite a lot of time and effort fighting the cult, won’t stab you in the face. These are mere gatherings of like-minded individuals, where hypothetical conversations about forcing one’s fellow citizens to adopt jointed antlers on their posteriors are discussed in a frank and open fashion! What’s the fuss? Surely this isn’t the literal end of the world.

Honestly, it’s weird. It’s weird within the setting, but it’s also weird as a function of the gameplay. Now, I appreciate that semi-cooperation is the toughest mode to navigate. It throws players into chaos, forcing everybody to navigate the theoretical boundaries between one loss and another. Is it a worse failure to lose together or to lose apart? Why should I help the group if I’m not currently winning?

The problem here, though, is that there isn’t really any response to a player investing in the cult, apart from trying to become a better cultist. Other titles, including some profound offerings from the past few years, have investigated the mode’s spurious social spaces. In Alex Knight’s Land and Freedom, the uncertainty of the glory bag (ew) makes it possible for trailing players to win, thus keeping them in the fight. In Jo Kelly and Cole Wehrle’s Molly House, betrayal is one further risk among many, opening the path to social shunning and openly declared a lesser victory than remaining faithful to the community. And lest those games earn a pass because they’re highfalutin’ historical titles, even Kevin Wilson’s own Escape from New York lets you conk a faithless ally on the noggin and steal their junk. By contrast, betrayal in Kinfire Council comes across as an appendage, not an essential organ. It’s a pinkie sprouted from your cheekbone. What am I going to do with this, prod my own eye?

Without the possibility of betrayal, though, Kinfire Council is too boilerplate for its own good. It’s a solid boilerplate, to be clear, handsomely produced and with a tremendous sense of character and setting, and it isn’t as though I’ve begrudged my fifth visit to Wilson’s gorgeous apocalypse. But Kinfire Delve and Kinfire Chronicles, despite the occasional flaw, were fully coherent in their gameplay. Without the possibility of betrayal — betrayal that matters, that’s interesting to engage in and oppose, that bears significant import to the table at large — the entire endeavor feels watered down.

But, sure, running the Din’Lux HOA isn’t all bad. Problems crop up that must be addressed. Nobody wants to pay for anything that doesn’t benefit them directly. There’s a spreadsheet. The personalities kinda blend together. It’s a nice neighborhood for a visit. They’ve got a great pool. But I think I’d rather hang my hat somewhere else.

A complimentary copy of Kinfire Council was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my second-quarter update!)

Posted on August 22, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Incredible Dream Studios, Kinfire Council. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0