Skyblivionrockmarsh

Way back in 2011, Todd Howard let it slip that Skyrim would have “unlimited dragons,” dragging surprised reactions from the internet. Don’t believe me? Here’s pre-People Make Games, pre-Shut Up & Sit Down Quintin Smith’s press release on the matter. It’s pleasingly sarcastic. Because, you know, “unlimited nouns” has always been the Elder Scrolls’ whole thing. This is the fantasy series that made volume its defining metric. Depth? Nah. Enjoyment? Get outta here. Kelvins? Only if you’re talking about Lord Kelvyn, the Redguard Knight of the True Horn. No, really. Like I said, unlimited nouns.

Which brings us to The Elder Scrolls: Betrayal of the Second Era, Chip Theory’s adaptation of not only Skyrim, not only Oblivion, not only Morrowind, not only those other ones nobody talks about anymore, but the whole dang universe with its boundless recreations, provided your recreational interests are limited to hoofing across fantasy landscapes and murdering fantasy gobbos. It comes with a bazillion components, weighs so much that it should have a team lift warning on the box, and costs as much as twenty-five burritos from my favorite local burrito place.

You heard that right. Despite my policy on the matter, this thing is so pricey that I think it warrants some discussion. First, though, I want to walk you through the shape of an average TES:BOTSE campaign.

Learning a Chip Theory title is a chore. There, I said the brave thing. It took courage just to unwrap all the components, and my first summer job was as a lion tamer. (Don’t fact-check me.)

The list starts out well enough, a few adventurer mats and double-sided maps. Then it explodes. Twenty adventurer chips. Sixty-five monster chips. (Double-sided monster chips!) Over 150 dice. Over 300 cards. Five separate adventure books. The rulebook is just shy of a hundred pages. There’s a tutorial guide that’s longer than some novellas. Now where’s the tutorial guide to the tutorial guide?

Fortunately, there is actually a tutorial guide to the tutorial guide. It’s an app through DIZED, and it holds your hand through the process of learning the game. It takes a while — two to four hours, depending on how hurriedly you click through pages you think you understand, and then how hurriedly you click back to remind yourself of the stuff you hurried past the first time — and there are some gaps in a few of its explanations. But as a first session, it gets the job done. Enough so that I could tackle the rulebook and recognize the difference between the things I’d learned already and the stuff I needed to brush up on.

Campaigns begin with character creation. There are two ways to go about this. Either you can throw yourself into an introductory scenario — yes, as in Elder Scrolls tradition it’s a jailbreak — which defines your character’s race and a few starting skills, followed by a selection of classes that depend on how you handled yourself. Or you can do what I settled on every time I knuckled down on the campaign, which is to create your character by throwing together some races, classes, and starting skills, and seeing how your baby fares as they take their first tentative steps into the world.

Here’s the good news. As far as I can tell, the skills on display are varied but effective, allowing a wide range of play styles. Provided, of course, your chosen play style is “kill things from up close,” “kill things from far away,” or “kill things with sparkles from your fingertips.”

This is, after all, a combat game, and Chip Theory is no slouch when it comes to crafting engaging combat. There are ups and downs to this process, which we’ll get into momentarily, but Betrayal of the Second Era sets a high bar. My three characters felt distinct despite more or less accomplishing the same thing. In my first campaign, my sword-and-board orc struck a tight middle ground between dealing damage and huddling behind cover. Later, I crafted a two-handed glass cannon who liked to tire herself out, but could also churn her fatigue into a second wind that happened to be a tornado filled with glass shards. After that, I made a magic user who alternated between red-misting enemies (but also sometimes herself) and summoning tanky mooks to the battlefield to distract enemies while she wrestled her spells into hurting the correct targets.

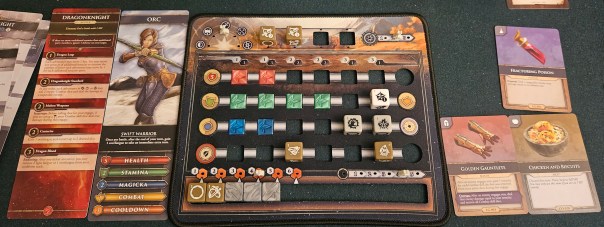

The dice system is the clear highlight here. Characters gain skills from trainers in town. They can then spend experience points to add dice to those skills. Rather smartly, every character is limited to only four “skill lines,” which isn’t quite enough to build a well-rounded character, especially when three of your skills are health, stamina, and mana, two of which aren’t even allowed to be de-trained. (Coward! Let me play with zero hit points!)

The solution is that each skill line can hold two separate skills. It’s just that those skills lie at opposite ends of the row. This means they’ll eventually horn in on their opposite skill’s territory. If you want a lot of health, then, you should make sure that its opposite skill won’t take up too much space. In practice, I usually crammed a modest healing spell or armor trait next to my health, affording some protection but not capping my hit points too severely. Meanwhile, my main combat skill received almost an entire row to itself, letting me amass big piles of dice.

Those dice, by the way, are given plenty of range. The most common option is single activation: you roll a die, apply its effect, and then stick it at the bottom of your character sheet, where it gradually cools down and re-enters your pool. Others might become active, sticking around until you use them — usually defensive traits, like holding up a shield — while others are single-use dice that are drained for the rest of the battle, and others still are only active while they sit in your cooldown track.

Speaking of the cooldown track, where fatigue systems are concerned, this one offers clear and effective decisions without requiring much overhead. A little sword is crammed into your character sheet, clearly indicating how many dice you can refresh each round. There are constant tradeoffs between rolling a bunch of dice or only rolling as many as you can actually refresh. Meanwhile, you can take additional actions for some fatigue, gray or black cubes depending on the severity of your exhaustion, that do nothing but squat in your cooldown track. Unless, that is, you can transform them into healing or a berserker fury.

Hit points are represented by stacks of chips, a suitable nod to a company named Chip Theory Games, but also a useful visual metaphor for the relative threat of everything on the battlefield. Stack high? Kite that jerk. Stack low? Finish them off. Stack in the middle? Consider your options. Lots of stacks on all flanks? You done messed up.

On the whole, the combat system is truly impressive. It’s tactile in the best possible way, letting you move around dice and chips with every action, and provides clear visual cues for your character’s current range of abilities, cooldowns, vulnerability, and all the rest. Even status effects like bleeding or blindness are handled by sticking a die into your cooldown track. This is downright brilliant. Rather than having to check some sheet or token off to the side, you can see right there that your character is going to lose a hit point each turn or might bonk a buddy over the head instead of the nearest gobbo. This also provides clear stakes. Want to cure your blindness? Figure out how to withdraw the blindness die from your cooldown track. Easy.

Of course, Betrayal of the Second Era clutters this system in other ways. The big one is the many reference sheets for your skills. It’s often possible to mix and match dice in a single roll, resulting in creative outcomes that feel great to execute. But reaching that execution is something else, often requiring players to pore over the minute distinctions between one sword-slash icon and a related but crucially different sword-slash.

There are also a few, ahem, alternate skills as well. Like, say, talking to people. As is the case with everything else in Betrayal of the Second Era, these are given entire skill lines and dice traits — remember, the cardinal rule of the Elder Scrolls is “unlimited nouns” — but largely serve as duds best avoided while you search for better trainers. Every time I’ve tried to engage anybody in the finer points of Aetherian theology, for example, the game’s boundaries become stark. This is a combat game with the occasional contextual decision. And even then, the combat is limited to a particular style.

Somewhat interestingly, crafting the default archetype found in the Elder Scrolls video games — that’s right, the stealth archer — is possible, but not especially effective. Stealth means you can’t be attacked by non-adjacent enemies. But there’s a difference in mode between this board game and its digital inspirations. Rather than crawling through dungeons, where you can keep enemies at a distance and use stealth to your advantage, here encounters begin after the battle music has started. Your foes are numerous. They already know you’re here. They’re beelining toward your position. Their hands are waving around in stock animations that communicate an incoming fireball. It’s time to rumble.

To be clear, this isn’t a critique as such. If anything, combat is better than your average encounter in Skyrim. Battles in Betrayal of the Second Era are thoughtful affairs, not the janky crowded slapfests that are video game melees.

But they’re thoughtful in part because speed means missing out on a dozen particulars, and almost certainly elide some crucial rulings in the process. Enemy mobs are a jumble of keywords and special effects. The longest portion of any battle is right after setup, when everybody reads those keywords and stares half-dazed at the field in an attempt to sort through its topography of intersecting defenses, attack bonuses, status afflictions, and everything else. This abundance of keywords gives the game its texture. But it’s a rough texture, like sandpaper that occasionally has a knife stuck through it.

I realize I promised a description of the average Betrayal of the Second Age campaign, only to describe at length the dice and chips and combat. That’s on purpose. These campaigns are the combat, albeit combat with interspersions.

Generally, a campaign proceeds like this. In your first session, you pick a guild and a map. Say, today we’re headed to High Rock, and we’ve decided to become initiates in the Dark Brotherhood. This gives us a starting quest, pretty much always some destination far away, while our chosen map offers unique rules that govern things like movement or whether enemy forces will pursue us during our adventures.

We have twelve days to complete this quest. So we begin walking. We move across the map, stopping at various encounter sites or towns. Encounters usually spark battles — even some of the “peaceful” options are ambushes — most of which are smartly limited to a single battle map. Towns let us rest, meet trainers, accept side quests, obtain items from merchants, and offer their own snippets of narrative and special activities. Along the way, we might be treated to a delve, a multi-part explorative encounter that has us dynamically assemble a map, bypass its denizens, and steal its goodies. These are more complicated than your usual battle, but also more interesting.

Eventually, after maybe three to a half-dozen fights, we reach the climactic final battle. These feature special rules (sometimes too many special rules) and big battlefields, testing the characters we’ve honed over the past three hours.

And then we do it again, this time on a second map. If we succeed there, we face a third act, this one not on the main map at all, but a series of big fights that are meant to put our skills to the test. Although in fine Elder Scrolls fashion, by then we’re usually so overpowered that we’re one-shotting giants and any number of bandits wearing improbable daedric armor.

This power curve is deeply satisfying. Where early fights are tough, our health and cooldown tracks barely keeping pace, by the final act we’ve evolved into demigods. There are still challenges, but again they’re questions of volume, entire football teams of high-level hooligans blitzing our position. It’s a relief that Betrayal of the Second Era doesn’t spill beyond those three acts. Three sessions provides enough room to develop a team, but doesn’t overstay its welcome — or allow us to curb-stomp our opposition with too much ease.

Okay, so Betrayal of the Second Era is good. Certainly it’s much better than I was expecting, as a player whose previous experiences with Chip Theory productions have been lackluster. But is it good to the tune of two hundred and fifty of American Jesus’s greenbacks?

There’s a reason I don’t discuss price. More than one reason. Assuming you’re American, and assuming your socioeconomic situation is roughly in line with my own, and assuming you spend as much time as I do playing board games, and assuming you don’t mind forgoing a balanced diet for hot dogs this week, and assuming you bounce between titles as rapidly as I do, and assuming you have a group of likeminded nerds… which, yeah, is very quickly demonstrating why I don’t talk about per-dollar value.

But when it comes to Betrayal of the Second Era, value is a fair question. Not only because it costs a fourth of a car (in 1886), but also because it feels like a consumer product. And, look, obviously 99% of the board games I write about here are consumer products. But many of them have artistic or cultural or historical objectives as well. I’m not especially interested in helping move product. I want to connect people with experiences that will be meaningful in some way.

Playing Betrayal of the Second Era, it was hard to escape the feeling that every moment had some specific worth, measured in dollars and cents. I didn’t even pay for the thing, and I could still hear the clack of some unseen abacus behind every moment. Sure, my group was having a good time. Many of the systems have been crafted to perfection. But it also feels like much of the game’s cruft has been created specifically to fulfill an imaginary value proposition. The maps are all slightly different, but remain so very similar. The hundreds of encounters add little wrinkles to their combat encounters, but for the most part they’re more differentiated by the random enemies that get seeded onto the battlefield. There are heaps of items, all with slightly different effects, and most of them are junk. The storage solution that pins your character board in place, complete with its upgrades and dice… well, that’s super. Really, I wish other campaign games were this easy to store.

Personally, though, while I had a tremendous time completing three campaigns, I don’t quite think it was worth three to five times more than, say, Tidal Blades 2, or Sleeping Gods: Distant Skies, or Purple Haze, or Kinfire Chronicles. In some ways, maybe even many ways, it has ideas and systems and design tics that are better than those games! But three to five times better?

Not for me. Maybe for you. Surely for the dude who shows up in the comments to talk about how he’s played 250 hours of this game and still hasn’t seen everything, and that makes it the strongest cent-per-hour value of anything he’s ever purchased. And bully for you, my dude! That’s so great! I’m genuinely happy for you! But for me, I wish Betrayal of the Second Era had been more compact. That it hadn’t given me quite so many units, encounters, maps, scenarios, and items, all of which are distinct, but in many cases only slightly distinct, in ways that don’t quite matter to the tone of the overall experience. In some ways this is a stellar adaptation of the Elder Scrolls, and in some ways it’s unfaithful — usually in ways that are far superior to the video game series. But of all the things to adapt, “unlimited nouns” is not what I was looking for.

You know. IMO.

TES:BOTSE is at its best when it offers distinct scenarios, usually as crowning moments to each session.

As I’ve noted, though, I was left deeply impressed by Betrayal of the Second Era. It takes a world that’s always felt generic to me and made it… well, still generic, but vibrant as well, especially when it comes to the character crafting. It’s a delight transforming a sprung inmate into a bastard who slings claymores and fireballs, and can also talk themselves out of a corner once per session. That the game accomplishes this transformation in three relatively brief (two to three hours apiece) acts is even better.

Here’s the short version. This is a luxury car of a board game. Such a delight to drive, somewhat over-specialized, and likely out of reach. Might I recommend a rideshare? If you pay shipping and pinkie-promise you’ll pass it along to somebody else when you’re finished, you can take my copy.

Complimentary copies of The Elder Scrolls: Betrayal of the Second Era and the Valenwood expansion were provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read the first part in my series on fun, games, art, and play!)

Posted on June 19, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Alone Time, Board Games, Chip Theory Games, The Elder Scrolls: Betrayal of the Second Era. Bookmark the permalink. 7 Comments.

i can definitely agree to those ride sharing terms!

This interface is a drag in how it arbitrarily prevents me from resuming writing, or deletes all that I’ve written so I must start over. (At least that’s how it’s functioning on my IPhone.)

Neither a video game nor a board game can provide the full, wide-open experience offered by a good human-moderated RPG. On the flip side, while to be game master can cost very little in material, it can consume a lot of time in preparation between sessions. Either that’s itself a big part of one’s fun, or it’s labor for which someone might find it worthwhile to pay.

Another factor is that the narrower focus typical of video games seems to be what a lot of folks really wanted back when the paper-and-pencil D&D game was their makeshift because they couldn’t afford the two grand or so (in 1980s dollars) that the Apple II hardware to run the software would cost.

I don’t even agree with those aver that video games or board games do better the “dungeon game” that was such a big draw half a century ago; I enjoy more the kinds of puzzles and negotiations that characterize the old-fashioned form, which don’t lend themselves as well to rigid rules sets and the limitations of a program to dealing with what the programmers anticipated (not “out of the box” emergent play).

Again, in my experience of historical simulations, whereas a larger demographic is more pleased by the locking away of the model in a machine-language black box, I find engaging with that expression of the author’s thesis part of my enjoyment. Perhaps it’s like books; what would a Cliff’s Notes version of Burton’s _Anatomy of Melancholy_ or Joyce’s _Finnegan’s Wake_ provide that’s worth the lesser time to read?

I guess it’s a good thing we don’t all like the same things, else what a haggis shortage there’d be!

Incidentally, I think the price of a Benz Patent Motor Carriage was $1,000. However, I’m no expert (so for all I know, you might be).

Please forgive me for something that’s off on a tangent, but I’m thinking about the phenomenon of people in various venues remarking on it seeming as if game design has hit a slump in innovation.

I think it’s fairly natural that this has occurred. I think one might point to a roughly decade and a half long period of intensive exploration in the ‘Euro’ field (tapering off circa 2010) and previous longer but less intensive, roughly two-decade period in the historical wargames field (tapering off a couple of years before the ‘Euro’ boom started).

The wargames period was less intensive because in that field the design paradigm starts with the premise and then chooses mechanics to model the subject. Mechanics for the sake of their own interest are not a high priority.

Anyhow, the periods of intensive exploration found the low-hanging fruits, the contrivances (among those that enough more people find fun to play than the less commercially successful experiments of designers such as Leo Colovini) that require a muse merely as rare as one several thousands instead of one in several tens of thousand.

This might tie back in to the trend of heavy boxes with heavy prices (with which many have also noted a correlation of the rise of crowdfunding). When Colt’s old “NEW and Improved” advertising slogan doesn’t have much traction, “BIGGER and Better” (or, I gather, in Internet idiom, MOAR!) can sell to a segment of the market.

Good review, Dan, very informative.

Side note. Do we think the above commenter is a bot?

Thanks, Shinzawi.

Side note: I don’t think so.

Pingback: Life in First-Person | SPACE-BIFF!