Oh Friend Ah

Everything I know about ofrendas I either learned from Coco or Spectre. Okay, it isn’t as bad as all that — twenty-five years ago, I also played Grim Fandango.

Regardless, it’s fair to say that I was eager to learn more from Orlando Sá and André Santos’s Ofrenda, the board game version of the practice. I came away surprised by the depth of the gameplay, but no more informed about the particulars.

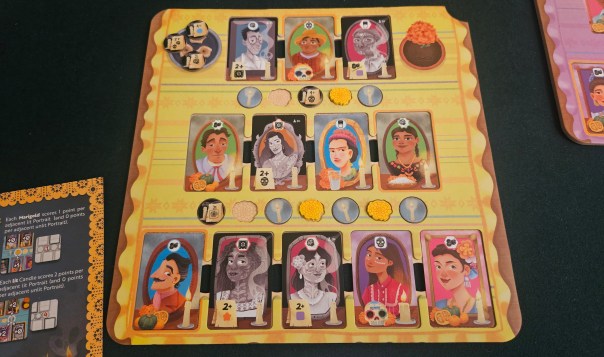

As befits the title, Ofrenda is all about arranging an ofrenda, positioning candles, marigolds, and portraits of the deceased, paired with their favored offerings, in arrangements that will hopefully draw their spirits to visit your shrine.

It’s also a surprisingly catty experience, close kin to the juggling act that is seating family members at weddings or other events. Look, once again I’ll confess that I don’t know anything about ofrendas, so maybe it’s customary to arrange one’s photographs to keep Great Aunt Helen away from that “gold-digger” sister-in-law of hers, but the result is lightly comedic, ticking between warm and frustrating as your departed kin prove just as souciant in death as they were in life.

Each round revolves around a single photograph. Players draft these from a river-style marketplace — ostensibly our cousins were strict about only developing a single photo apiece — and then either place it somewhere in our ofrenda or throw it away for some additional marigolds. The card illustrations by Álex Herrerías are lovely, showing skeletal images on one side and more vibrant colors as they awaken, providing a stark visual rubric for the overall health of your shrine.

Awakening a spirit is tougher than it might first seem. Each photograph belongs to one of five color-coded branches of the family and provides an offering, whether a glass of water, some fruit, sugar skulls, decorative tissue paper, or salt. Spirits also have needs. Some of these are simple enough: an aversion to salt and water, a desire to be placed near some fruit, a dislike for those people in the family. Others are more stringent, such as those who will only flip to their enlivened side when positioned by family members who meet certain criteria.

Like I said, it’s lightly comedic, and tucking Grandpa into a corner because he will only abide purple cards or those showing calaveras is certainly amusing. The lion’s share of your points come from those face-up portraits, and Sá and Santos have done the right thing by making it near impossible to please everybody. There’s a necessary degree of prioritization, especially in the slots of your ofrenda that double their points when the game concludes. It calls to mind the outcast table at any sufficiently large wedding, where the cranks are stuck so they can pester each other rather than ruining everybody else’s party.

Other little elements stand out as well. Marigolds are the game’s primary currency, letting you skip slots in the market, but can also be arranged in specific spots of your ofrenda for a few extra points. The same goes for candles, although their requirements are more stringent, often generating little contests between players to have the most portraits in some category. There’s plenty to think about, although the random nature of the marketplace tends to see plans falling into place or not, rather than allowing players to feel clever in their own right.

The finest touches are those that spark some degree of reflection: a portrait of a woman bowing her beloved violin, a man posing with his pet, a luchador in his mascara, a child. There’s an appreciable gentleness to the whole thing, a warmth that comes through even in cardboard.

At the same time, there’s a disconnect between the game and its players that the authors seem uninterested in bridging. The game adopts a formalist stance, all symbols but no meaning, and even then only particular symbols are included, physical offerings but none of the saints or religious icons that often mark such a shrine. I’m not interested in speculating too deeply on these omissions. I’m sure there are many ways to honor one’s ancestors with an ofrenda, some Christian and others irreligious, some superstitious or grounded in tradition, rooted in the Cross or Azteca or otherwise.

But the effect here is that Ofrenda only broaches its topic furtively. It’s beautiful to look at, certainly, and doesn’t hurt to play. But its gameplay is thin enough for a tableau-builder that it doesn’t beckon the player to return, and there isn’t any essential spark of meaning that communicates anything particularly devotional or even interesting. Board games regularly deploy their settings as veneers, so that’s no great crime here, but it is a shame that Ofrenda should come across as so ordinary.

Ultimately, though, that’s where this one lands. Ofrenda is ordinary, stuck in the mundane despite its ethereal subject matter. I would have loved to see it enlivened. Perhaps somebody positioned it too closely to its least-favorite relatives.

A complimentary copy of Ofrenda was provided by the publisher.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read the first part in my series on fun, games, art, and play!)

Posted on May 20, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Ofrenda, Osprey Games. Bookmark the permalink. 4 Comments.

To be fair, the designers probably learned everything they know about ofrendas from Coco and Spectre as well. To be double fair, I come from a VERY Catholic family and we have never once put a cross in our ofrenda.

This.

I mean. Dia de los muertos is already a festivity plagued by syncretism. Even Skyfall molded how is celebrated now in Mexico’s biggest cities practically there was no parade before the movie and now is something expected, specially in Mexico city for tourism.

Even for me, as a mexican, will be really difficult to select in which parts to focus for meaning. I am from a region where there was a kind of parade but focused on a very regional symbol (Los Huehues that is the word for Old man in Nahuatl). I could not expect to see them in a board game as much as I cannot see them on all the country except for that specific region.

What I’m trying to say is that every region has it’s own meanings over the same symbols. There are ofrendas everywhere, but they are different. There are parades, but some are pranksters, other are solemn gatherings and some are just the kids taking halloween creating its own meaning of it. So, in that regard, maybe the lack of meaning over the symbols is not so far fetched.

Do you mean the Danza de los Viejitos? It’s one of my favourite regional dances! I had no idea it was related to Día de Muertos, here in Mexico City we get a hodge-podge of everything.

It’s something similar. We also have the Danza de los Viejitos that, if i’m remember correctly, is not necessarily related to a specific date. But the Huehues are specific for Dia de los Muertos. I’m not fully versed on the origin of those traditions but I guess I can see the Danza de los Viejitos influencing the Huehue tradition as a new flavor for the Dia de los muertos.