Here Lies Every Other Detective Game

Dear reader, I think I’m falling in love… with the design collective Jasper Beatrix. Typeset offered our first furtive glance. Signal jumped us to second base. Yop. We move fast. Now that I’ve played Here Lies, we’re already booking venues for the wedding breakfast.

At a glance, Here Lies swims in the same waters as Signal. It’s also a deduction game, a one-plus-many cooperative affair where a lone player works as the “lead investigator,” more or less the silent alien from Signal, here to assist everybody else as they deduce the answers to a secret message. Despite its modal similarities, though, Here Lies carves out its own identity. More than that, it embraces an entirely fresh approach to deduction. There’s nothing quite like it.

In the beginning, there’s a case. A cold case, described by the lead investigator in that familiar secondhand fashion from old detective stories. “It was many years ago,” they begin, eventually filling you in on the details of the one case that stymied their understanding. Little by little, details are added. Fragments of evidence are penned onto the cards and deposited across a tableau, doubtless a mind-palace rendition of the corpse on the mortuary slab, questions are asked and answered, and, eventually, players take a stab at filling in the case’s lingering gaps.

Reading the rulebook, it all sounded like magic. That or a role-playing event, with players riffing on the evidence and crafting the case as they went. Thankfully, Here Lies is more solid than that, more board game than RPG, with discrete phases and concrete rules about what the lead investigator can and cannot fabricate. There’s some riffing, a pinch of improvisation, but this is not one of those collaborative story-writing exercises that some BG-RPG hybrids resort to.

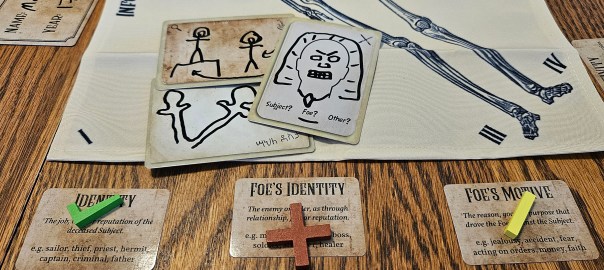

Instead, Here Lies carefully delineates its roles. As the lead investigator, you know the details of the case. There are six categories to solve, stuff like the identity of the victim or assailant, where the murder took place, the weapon or motive, or perhaps even more nebulous concepts like a secret (“a critical thing about the victim’s life they kept hidden”) or feeling (“an emotion or need of the victim that interferes or motivates”). Each of these categories offers a secret underlined word. To succeed, you must prompt the others at the table to state these words aloud at specific junctures.

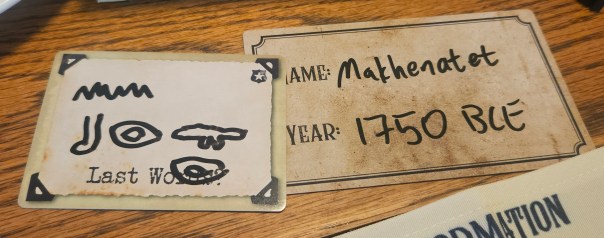

As the other investigators, you know very little. Hardly anything, in fact. The shared briefings are usually framing stories, vignettes about how an aged Sherlock Holmes decides to share the details of an unpublicized case in the privacy of some smoky drawing-room. The early details are minor: the name of the deceased, if indeed one is known, the year of the case, and a scrap of key evidence. It’s hardly anything to go on.

What follows is unlike any other detective game out there. In a normal detective game, you would now begin visiting witnesses, examining evidence, cross-referencing notes. There would likely be further snippets of dialogue and description to read through. The whole thing would grind to a halt. Somebody would move to the couch, leaning back with eyes closed. Not sleeping. Just thinking.

But there are no witnesses to grill, no crime scenes to pick over. There aren’t even paragraphs of information to read aloud. Indeed, given Beatrix’s compact form factor, the scenario book, which includes twenty-five cases in all, limits its details to two small pages apiece. I’ve been handed religious pamphlets that were more verbose.

Here, rather than being presented with scraps of evidence and sifting clues from red herrings, the case is turned over the investigators. They then pick apart the details by… well, by doing a whole bunch of stuff. At a mechanical level, there’s nothing radical going on here. Each round offers a certain number of time tokens. Investigators draw cards from their personal decks and spend those tokens to trigger them.

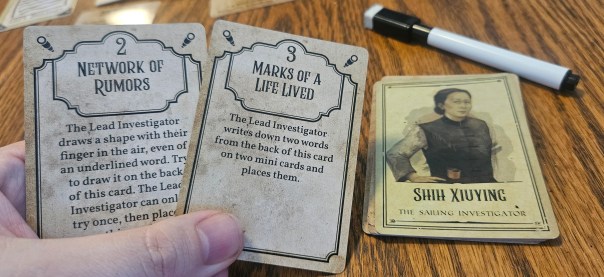

But the specific function of those cards sets Here Lies apart from its peers. Depending on your investigator, you’re presented with multiple ways to gather information. These methods depend on your identity. Sherlock Holmes, famous for his deductive reasoning, tends to spin out further clues by asking pointed questions. One of his cards lets the lead investigator circle letters from the alphabet, creating an anagram for the rest of the table to solve. Another jots down a word from the lead investigator’s private description of the case. Yet another allows the lead investigator to craft a title for the current case, using only “the case of the” followed by three additional words. It might not sound like a lot, but coming up with the right title can fill in quite a few blanks. “The Case of the Failed Forest Switcheroo.” “The Case of the Mummy Mommy Mummer.” Have fun with it.

The other detectives offer their own approaches. One of them is a mind artist. What is a mind artist, you ask? A mind artist is the guy who forces the lead investigator to draw stick figure vignettes of the crime scene, sketch curly lines that are then placed somewhere on the board, or play color-association games with the murder weapon. One of his most interesting cards lets the lead investigator draw a detailed scene, only for the others to announce which half of it will be erased before it’s revealed to the table. This produces a partial image, key details wiped from existence, with hopefully enough still intact to pounce on that one clue you’re missing.

Or there’s the mortician. Many of her clues are physically arranged atop the murdered body in the mind palace, zeroing in on the grubbiness or injuries suffered by the victim. My favorite, though, is the one that lets the lead investigator write the name of any person, real or fictional, on the card. By selecting somebody who bears some resemblance to the case at hand, you can scatter breadcrumbs that might break the case through association.

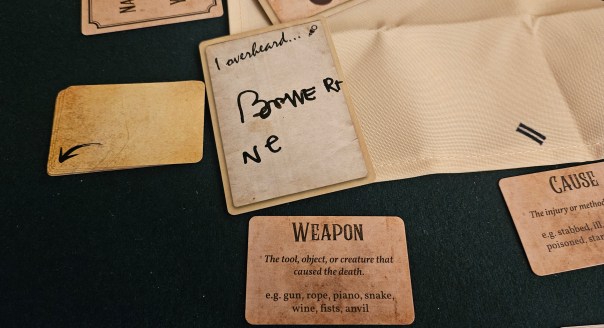

Or maybe you’ll play as the private eye. She receives hard-boiled clues, like the victim’s last three words or the identity of a new witness. Or perhaps the sailing investigator. She… well, okay, she seems to exhibit the least thematic consistency. Maybe she’s the recipient of all the clever leftovers that Jasper Beatrix came up with. But there’s a certain poetic quality to her stuff. Like the one card that lets her jot down three words, which the lead investigator is then permitted to erase in whole or in part, whittling the possibilities down to a few essentials.

Regardless of your actual identity, Here Lies emphasizes a tonally different sort of investigation from other detective games. I’ve enjoyed plenty of the genre’s offerings in the past, but they have an unfortunate tendency to blend together. More than that, their default mode emphasizes collation over all else. The killer had a mustache! So-and-so visited the barber two days after the murder! Except looking at the calendar, you realize the barber-visitor visited the barber the week before the killing! Oh no!

Here Lies could not walk a more distinct path. You’re still collating evidence, but that evidence is abstract, sometimes even ridiculous. One moment you’re playing hangman — the actual let’s-survive-this-boring-church-meeting activity, using limited letters to spell one of those all-important underlined words — and the next the lead investigator will be drawing a picture with their finger in the air while everybody takes frantic dictation.

It’s funny the way a shorter Sherlock Holmes story can be funny, your investigators making absurd leaps that only make a lick of sense within the logic presented by the game. The example that comes to mind is “The Five Orange Pips,” that one where Holmes figures out that the Ku Klux Klan was involved in a series of murders because of some wackadoo offhand remark. (And in which Sir Arthur Conan Doyle invents a completely false, but very amusing, etymological origin for the KKK.) Here Lies is like that, over and over again.

In emphasizing creativity over brute deduction, a certain fuzziness bubbles to the surface, which I suspect some players will struggle with. At the same time, this is also the source of the game’s most interesting moments, not to mention its kinship to Signal. It isn’t enough to find a clue. These clues must also be checked, as in Signal’s sequential experiments, detectives bouncing ideas and prompts against one another until something sticks. The gray-area nature of language plays its own role, especially when the lead investigator assesses the group’s answers as being right, wrong, or on the right track. That vagueness is essential to making the game work, guiding everybody along a shared path until their proximity to the correct answers becomes undeniable.

It’s like leading a pack of kids through a darkened bouncy house; there will be tumbles, but none of them are bruising. Once, as the lead investigator, I was prompted to reveal the victim’s final three words. Since the victim was an Egyptian four millennia dead, I jotted those words down in hieroglyphics. There was something specific I was trying to communicate, a detail about the victim’s locale at the time of death that my choice of images might have uncovered. Instead, my friends spent the next ten minutes trying to translate ancient Egyptian. It was hilarious and frustrating and a perfect fit for a pulpy detective story.

That’s how most sessions of Here Lies go. There’s a slender gap between the joyous absurdity of its cards and the rigor demanded by its prompts. That’s where the game thrives, generating a frisson of discovery that’s at once silly, logical, and exciting. It’s one thing to solve a murder by comparing spreadsheets. It’s another entirely to solve it by asking philosophical questions, playing word associations, and commanding one of your friends to reenact a scene through gestures alone. In the process, Here Lies establishes itself as paradoxically more similar to Sherlock Holmes stories than any number of other deduction games, all wild leaps of logic and preposterous clues.

In other words, another resounding success from Jasper Beatrix. I can already taste the wedding cake.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read my quarterly report on all things board games!)

A complimentary copy of Here Lies was provided by the publisher.

Posted on April 23, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, DVC Games, Here Lies. Bookmark the permalink. 14 Comments.

This looks phenomenal. Thank you for this piece!

Thanks for reading!

Great review! Curious between Signal and Here Lies which one you prefer, even if ever so slightly. Both sound great, but also the gist sounds quite similar. Excited to see what else Jasper Beatrix puts out!

I prefer Signal, personally — it’s a little purer, easier to explain, and feels wholly distinct with each play. Or maybe I just prefer first contact stories to detective fare.

While it shares DNA with Signal, its fresh approach to collaborative puzzles—where a lead investigator guides silent sleuthing—feels like uncovering hidden layers in a gravity-defying puzzle. A must-try for fans of cerebral twists.

Sorry, didn’t find a clue. So lead investigator knows all answers? Or just part of it?

The lead investigator knows the answers.

Pingback: Fear Factory | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Space-Cast! #46. Screaming Sherlock | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Whispers-in-Leaves | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Categorize My Thing Thing | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Most Select of Board Games | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Cutting the Cottage Pie | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2025! Beatrixmania! | SPACE-BIFF!