Climb Ev’ry (Other) Mountain

Sigh.

Solstis is a puzzle. Not in the game sense, where you’re trying to figure something out. More like it’s an actual puzzle that somebody handed to a pair of designers, Bruno Cathala and Corentin Lebrat, and said, “Please make a game around this puzzle.” To which they replied, “Sure, haha,” and then spent the rest of the afternoon talking philosophy before remembering their assignment and slapping the whole thing together in twenty minutes.

Speaking of puzzles, Solstis has me seriously reevaluating my policy of playing every game three times before I review it. Solstis barely supports a quarter play, let alone a complete trio.

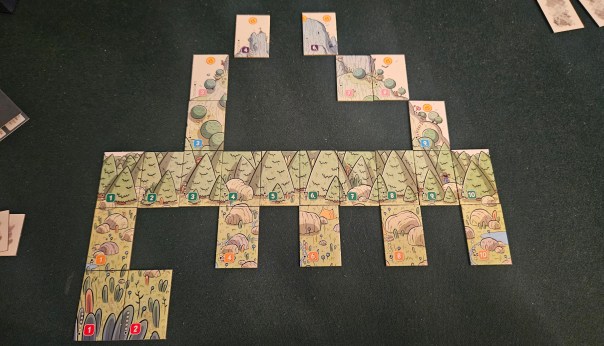

Picture this, if you will. A vernal mountain, green and blossoming, illustrated nicely enough by Manu Gorobeï, cut into forty-eight rectangular tiles.

Your task, broadly speaking, is to put some of those tiles together. You want at least one big patch of contiguous hillside, as your largest section scores for each tile. You also want to trace a path from base to summit, allowing you to score extra for the little bonfire icons at the top. Finally, completing any two-by-two sections allows you to draw and place a spirit tile. More on those in a moment.

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with this setup. The imagery is pleasant enough. The scoring is nice and clear. What gives?

What gives is that Solstis doesn’t bother to produce any gameplay. On your turn, you compare a tile from your hand against those in the market. If you can find a match, whether for your tile’s column or row, you get to pick up both tiles and affix them into your panorama. Otherwise… well, you get an extra try. The failed tile from your hand is added to the market, and then you draw one at random from the pool to attempt another match. If that also fails then you get a rainbow tile, which can fit anywhere, and your failed tiles are added to the market for your partner to potentially use as matches.

There are decisions to be made, but they’re sparse on the ground, and moreover they’re only rarely the kind of decisions that boot up anyone’s gray matter. More often, you’re presented a choice between two tiles that don’t actually work very well together, or there will be such an obvious choice that it wasn’t much of a choice to begin with.

The grand exception is the spirit tiles. As I mentioned, making a two-by-two block lets you claim a spirit. These introduce little tweaks to the formula, some offering an instant benefit and others adding an extra scoring goal for the game’s end.

Which brings us right back around again to the whole “not making decisions” bear.

It’s a dangerous bear, and not necessarily for the reasons you might expect. Because, look, board games don’t require decisions. They just don’t. There are plenty of games that don’t include decisions, or at least not decisions the way we usually conceive of them, and some of them are even very interesting, compelling, and enjoyable games.

Some will disagree. C. Thi Nguyen has argued that games are the form of art that uses human agency as its canvas. That’s a perfectly satisfactory definition. It cuts through the argumentation of those who would prefer to exclude games from the long list of things that qualify as art. That’s useful!

But as a comprehensive or all-inclusive definition, it doesn’t really account for a wide swath of things that are very definitely games but which include no decisions, only very minor decisions, or certain meta-decisions about whether to play the game at all. Like, for instance, a number of wagering games. Which, by the way, constitute the majority of things we would recognize as board games across much of human history.

So when I say that Solstis doesn’t contain interesting decisions, I’m not arguing that this is a bad game because it doesn’t pass some imaginary threshold of choices. It isn’t that this game needs to be more than a jigsaw puzzle to be enjoyable. Rather, it’s that the specific design of this puzzle has been engineered in such a way as to minimize the enjoyability of those decisions.

Take, for example, the puzzle. Plenty of people use puzzles as games. Even jigsaw puzzles. Have you ever dumped out a jigsaw puzzle and then raced to see who among your family members could find a match the soonest? Good-natured contests and little collaborations like these arise naturally among siblings and friends. Those are games.

But in Solstis, the puzzle is labeled. Every piece. Not only does this clutter Gorobeï’s otherwise pleasant panorama, it also denatures the joy of finding a match. It’s a puzzle with an instruction manual. A jigsaw with big splotchy tags. Solstis instructs players to find matches, but deprives them of the central pleasure of doing so.

The same goes for those spirits. If only they mattered more. Most of the time, they appear so late in the game that there isn’t much point to chasing a new objective. Either you pull a tile that works well with what you’re doing or you don’t. Like the variable powers found in countless modern board games, the spirits are built around the concept of permitting a decision, but they don’t really serve that function. The choice they offer is illusory, and all the more unsatisfactory for it.

That’s Solstis in an acorn. In adhering to the customary logic that board games must contain decisions, and moreover decisions of a specific stripe, it deflates those decisions until they’re saggy and hollow. It’s a low-ambition effort from two talented designers. We won’t remember it a month from now.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi. Right now, supporters can read a 3,000-word overview of the forty-ish movies I saw in theaters in 2024.)

A complimentary copy of Solstis was provided by the publisher.

Posted on February 4, 2025, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Lumberjacks Studio, Solstis. Bookmark the permalink. 2 Comments.

Seems 100% reasonable to change or break a policy (3x play requirement) that isn’t always effective. I’m sure you also grapple with bothering to spend time and energy on writing up things you don’t especially appreciate in any way.

I wonder if there are creative new ways to share quick takes, rather than a one-size policy. For example, I’d probably value even more a short article simply giving a quick list of things in say the past quarter you’ve tried-but-didn’t-dig-into, perhaps with an invitation for anyone to recommend second-looks. (We’ve all at some point missed a rule or suggested guideline for a game that led to a potentially singular bad experience.)

In any case, as always, thanks for being such a thoughtful editorialist in this space.

Thanks for the kind words.

When it comes to the 3x play rule, I’m intensely wary of making exceptions. I have done so once or twice in the past, usually when the game is so hard to table that there’s really no option otherwise. In those cases, I’m always careful to point out that I’ve only played the game once. Still, I don’t want to make it a regular thing. The idea of a quarterly roundup isn’t such a bad idea, though. I’ll give that some thought.