Pink Mars

Volko Ruhnke’s COIN System sure has come a long way since Andean Abyss. It’s sobering to realize that it’s been twelve years since we stalked the mountains of Colombia for drug cartels and Communist insurgents. The system has always prioritized certain assumptions about adversarial state-building, but now, in its twelfth volume, with multiple spin-offs and grandchildren padding its family tree — not the least of which is Cole Wehrle’s Root — the main series has taken a hard left turn into the speculative. We’re a long way from those history classrooms and CIA factbooks now, grandpa.

Red Dust Rebellion is the first game by Jarrod Carmichael, although we took an early look at his forthcoming Shadow Moon Syndicates a couple months back. For the most part, this project is a surprisingly cozy fit for the COIN Series. Set two hundred years in the future, give or take, the usual geopolitical boundaries have been redrawn thanks to the game’s remote setting, the red planet itself. What’s that phrase about how history doesn’t repeat itself, but often rhymes? Yeah. That. Even thought it takes place 140 million miles away, Red Dust Rebellion is so familiar that it might as well be a roadmap.

I have a little ritual for card-driven wargames. As events resolve, I place them to the side in a face-down pile, taking care to preserve the order in which they appeared. Sometimes, if an event is meant to stay on the table for a while, I’ll jot a note on my phone, sandwiching the offending snippet so that I can restore its proper sequence. When the game ends, I carefully store the deck, facing its cards opposite the rest. Later, after everyone has gone home and I have a few minutes to myself, I’ll pull out the deck again and flip through the miniature history book of our session.

The COIN Series has always been amenable to this ritual. Its events index to the playbook, where the designer is permitted a few sentences to discuss the inclusion of that particular happening. In some cases, I’ll learn something new. Even when I don’t, the process is instructive. What might have happened if our historical procession had gone some other way, if Batista had fled two years earlier or Tet crashed against better-prepared forces. These are, at best, historical fiction. But they’re also the core of systems like COIN, little fantasies that let us test our model against the barriers of what actually happened.

In that regard, Red Dust Rebellion sticks to the format. Carmichael provides the same notes as Brian Train or Harold Buchanan. Its questions rhyme with those offered by its forebears. Would a revolution on Mars look like an American Revolution, whipped into a frenzy by its landed interests, or a labor uprising of Cuba? Would it include a religious dynamic, one of the gaps the series has never quite been able to resolve into focus, as in A Distant Plain? Would it be co-opted in its late stages by someone with enough charisma or cash to sway the masses? Who would be the China to its NVA, the United States to its ARVN?

Impressively, Carmichael answers these questions, even if his answers are as speculative as previous volumes’ sequencing. This process has always been sci-fi, or at least historical fiction, only now the rebar shows through the concrete.

The fault lines of this conflict are familiar, if only because Mars has come to symbolize a particular sort of resistance in popular culture. Whether we’re talking Red Faction, The Expanse, or, probably the most formative of them all, Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars trilogy — which Carmichael disclaims he has not read — these fractures are well established.

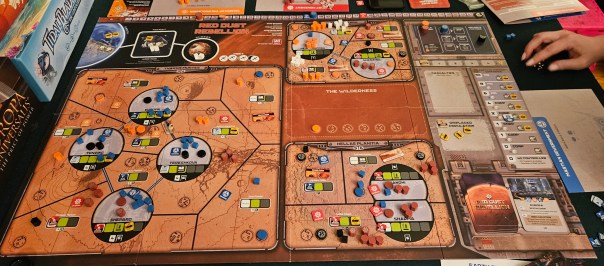

The main player, politically, is the Martian Government. MarsGov for short, this is the familiar blue-suited faction that polices the urban centers, struggles to project power into the rural corners of the planet, and is largely beholden to outside interests. The urban-rural divide, which has always reflected a certain assumption about which people deserve to have their support curried and which should be periodically sacked and then left to their own devices, is given stark lines when your atmosphere is so thin that it bleeds into outer space. Much of the Martian population is housed in labyrinths, subterranean cities carved into lava tubes and bedrock for shielding against all that wayward radiation. This is where MarsGov thrives, shuffling police between starports — the atmosphere’s thinness also precludes ordinary flight — and along razor-thin maglev lines. Life on Mars only survives in curated bubbles.

But those bubbles are not quite as strictly maintained as in previous COIN volumes. The Red Dust Movement, a worker uprising that hopes to shift Martian politics away from Earth’s grip, has strongholds of its own. The Martian surface offers roughly the same landmass as Earth thanks to its absence of oceans, and Red Dust Rebellion covers great swaths of territory. There are three main theaters, each focused on a cluster of labyrinths, and the Reds have a toehold in each. Their toughest nut to crack is the twinned labyrinths of Gandhi-Sharma in Hellas Planitia. They also have a broader view of the homesteads and unmarked labyrinths of the Martian outback. Depending on one’s perspective, they function like MarsGov’s shadow. Where the cops operate in the open, Red Dust keeps its insurgents hidden as long as possible, spreading their ideology through word of mouth and launching surprise attacks.

Again, though, the fragility of those bubbles is never far from mind. The bigger the fight, the more likely it is that the violence will crack the eggshell. When that happens, damage markers indicate a whole range of disasters, from violent decompression to chronic water shortages. This results in displaced population, not to mention fewer hearts and minds for the local factions to control. All the while, additional immigrants are arriving from Earth, and each token needs its own housing lest MarsGov appear incompetent.

The COIN Series has touched upon mobile populations in the past, first in Brian Train’s A Distant Plain, where Afghan returnees could be settled to shore up the government’s tenuous image, and also in multiple of the scenarios of Stephen Rangazas’s The British Way, where populations could be shunted to reservations to starve the guerrillas of support. Here, the concept receives its most robust depiction. Both MarsGov and Red Dust need to curry favor with the populace, so they go to great lengths to house those population markers, sway public opinion in their favor, and, if things are looking testy, deprive their rival of support by force. Again: bubbles and eggshells.

This is the game at its smartest and most brutal, if also its most fussy. It’s easy to misplace a population token. There are rules governing which markers are obliterated when a labyrinth is breached versus those that are merely displaced, alongside rules for fortifying against disaster. This can also result in shocking swings of fortune, such as when, in a recent session, the Red Dust Movement bombed the maglev line between Europa and Tenzing, killing thousands and displacing thousands more. So much for MarsGov’s base of power. Also, so much for the COIN Series’ recent trend away from complexity.

But these tradeoffs in complexity also allow Red Dust Rebellion to make certain advancements to the series as a whole. In some spots, these even read as interventions into the usual formula. Population is a big one, a reminder that some of the worst offenses against mankind occur when large numbers of people are forcibly displaced, and smart players will be on the lookout for ways to leverage large concentrations of human bodies to their advantage.

That’s hardly the only corrective Carmichael offers. There’s also the question of who’s pulling the strings. MarsGov operates on the patronage of Earth, the distant stand-in for the supporting role the United States occupied in many other volumes. Earth supplies the essential supplies that keep everything running, not to mention troops and satellites for bolstering MarsGov’s control over the red planet. But Earth has more than one puppet dancing from its tethers. The more ominous faction is the Corporations, moneyed interests determined to suck Mars dry of resources and assets. Clad in stark black and dropping security forces and spec ops from orbit, this faction might seem cartoonish at first brush, not all that far removed from the outlandish corporate interests of The Expanse. Then again, we happen to live in a world where sweaty-faced oligarchs boast about the end of democracy on television, so Carmichael gets a pass for not pretending that a handful of corporations laying claim to an entire planet would be a bad thing.

Perhaps most tellingly, the obligation between MarsGov and the Corporations on one side and Earth on the other runs both ways. At any given time, only one faction can direct Earth forces and assets. This results in constant bickering between ostensible allies, a touch reminiscent of some COIN Series high water marks, but handled with its own intricacies. MarsGov may be a jackbooted overlord, but it’s a jackbooted overlord that at least wants to repair damaged labyrinths and house all those displaced population tokens. The Corporations only care for such matters when they can be used to erode public trust in their bedfellows. Where every other faction frets over tangibles like population and support, resources and bases, the Corporations are driven by nothing but raw profit. They extract these profits principally through their terraforming bases, filling the atmosphere with greenhouse gasses that make Mars slowly more habitable but also more pliable to extraction. Every time one of those black bases flips to its advanced side, it’s a signal to everyone else at the table that Mars is growing a little less alien, a little more tamed.

The reverse of that coin is the Church of the Reclaimer. This is the most far-out of Red Dust Rebellion’s factions, a religion based on the preservation of Mars’s native landscape and the notion that humanity should adapt to their environment rather than polluting yet another world, but it’s also one of the game’s cleverest narrative choices. The Reclaimers are part Fremen, traveling in the dust storms that otherwise lock down portions of the map, part Robinson’s Areophany, a new religion for a new frontier.

With its twin focus on materialism and the right/left ideological divide, the COIN Series has always given religion short shrift. It’s only here, in Red Dust Rebellion, that humanity’s oldest and most enduring effort at explaining its own distinctiveness is given a fuller expression — albeit a strange one that some will undoubtedly find off-putting. The Reclaimers are cast as perennial newcomers. They care little about popular support, erode everybody else’s goals simultaneously, and employ their own currency, dumping the usual resource tracks in lieu of a separate deck of cards that can be spent for their own suite of operations. They even fall outside the usual initiative system that is COIN’s staple, spending those same cards to intrude into the usual procession of factional eligibility. They are, both narratively and systemically, outsiders. They are the strangers who are most at home in this strange land.

The Reclaimers are also the hallmark of a COIN game that isn’t hidebound by convention. Historians have long connected religious revitalization with previously unopened frontiers — Protestantism and the New World, the Second Great Awakening and Manifest Destiny — with all the rejuvenation and horror implied by baptism and rebirth. It’s natural to imagine that humanity’s first great step on the road to galactic civilization would force a similar reckoning. What sort of interstellar species are we going to be, exactly? Will we become wellsprings of transformation, able to inhabit any landscape thanks to modular implants and some anti-inflammatories, or will we wrack every biosphere until they’re stripped down to the narrow band we most comfortably inhabit?

In this way, Carmichael positions the fight for Martian independence not only as a struggle between corporatism and nativism, or federalism and individuality, but also for the very identity of mankind as a biological species. It’s tectonic in the same way as the development of capitalism or marxism, a realignment one can well imagine would be contested for centuries. It also questions the core assumptions levied by the game’s factions. The Red Dust Movement may be champions of the individual compared to MarsGov or the Corporations, but are they ready for the radical individualism of dust-filtering lungs and digestion of fine silicates? There are hints of contemporary concerns at play in the uncanny biological flexibility of the Reclaimers. I think back to how my childhood church preached that gay marriage would mean the end of traditional unions. Now those same neighbors have shifted to hand-wringing about how their grandchildren are being turned transgender. We always carry our baggage with us. Even to Mars.

If you can’t tell, I’m over the moon about Red Dust Rebellion. Carmichael has done something special here, bucking received wisdom in multiple ways. This is a more complicated volume, but the added load never feels misplaced. Its concerns are forward-thinking, but with the same reverence for history that has always been the series’ calling card. Even its science fiction elements are considered. They ask pointed questions about our priorities here, today, right now. Whether we’re okay with a two-tiered justice system that reduces public servants to corporate stooges. Whether we’ve eaten our fill of oligarchical apologia or need to stuff down a few more servings before our emaciated stomachs grow weary of the sawdust. Science fiction has always been a contemporary art, one that asks political and social questions that more grounded genres shy away from. In that regard, Red Dust Rebellion is an inheritor of multiple traditions. Where previous volumes have forced a confrontation with the past, this one confronts us where we sit in our living rooms.

To be clear, Red Dust Rebellion is a challenging course. A full session requires three or four hours, and while it isn’t as complex as certain COIN volumes — Fire in the Lake and Pendragon come to mind — it still requires study and concentration to become its fullest self, especially once its factions start bouncing off one another. More than once, I’ve seen a session end prematurely because something had gone overlooked, usually resulting in an early (unsatisfying) win.

But when the planets align, the syzygy is awe-inspiring. This is the best the mainline COIN Series has offered to date, a sprawling and evocative study in a pink-hued mirror. I hope what stares back at us is worth the fighting for.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on December 24, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, COIN Series, GMT Games, Red Dust Rebellion. Bookmark the permalink. 19 Comments.

I’m playing it for the first time in a group this weekend, very much looking forward to it!

Best of luck! Take it slow. There’s a lot to take in.

I LOVE the theme of this game, it shines through so strongly despite (or perhaps because of) all the little rules intricacies in this game. This COIN game is far from streamlined, but it also perhaps the best example in the series where every aspect of the game is designed to help tell the overarching story.

I just want to add that Mike Duncan of History of Rome podcast fame has just launched a new series about…. Revolution on Mars. The timing could not be better for providing some great backdrop material for this game (they are not set in the same universe, but they have a lot of overlap and it’s fun to listen to a “historical” podcast about the future).

https://revolutionspodcast.libsyn.com/

I’ve heard that! I’m still somewhere in the Haitian Revolution, but this might be the kick I need to catch up.

Really interested in this one, but your 3-4 hours sound optimistic… I see a lot of 5-8 hours, with promises to bring it down a bit with experience. So this becomes another struggle between the dream and the reality for me…

My longest session was around three and a half hours. Keeping the campaign limited to three dust storms (propaganda rounds) instead of four was a smart touch.

Oh great, makes me reconsider. As I said, I saw much longer game duration reports, but now I am interested again! Thanks Dan.

Ha, just now realizing this isn’t an expansion or spin off of Terraforming Mars.

might take a look!

Oh man, I wish Terraforming Mars were this ambitious!

Wonderful review, thank you, Dan! This definitely makes me curious to try this item, which I so far had largely been ignoring, at least once.Your opening paragraph, mentioning COIN’s many grandchildren including Root, suddenly makes me curious – did you ever play Tresham’s Revolution, the Dutch Revolt 1568-1648? A game that always struck me as something of not quite a father or mother but maybe a grandparent or great-uncle/aunt of the COIN series. Didn’t have the card based core mechanism, but certainly its five faction asymmetric setup and rebellion/counterinsurgency theme seem like something that would translate very easily into a COIN proper.

I have not played Revolution! I really ought to.

I’ve bloviated about this title on BGG, but this was easily a 6-hour game for four, though I quite agree it should be an hour per player. I would like it a lot more if it didn’t feel as long…I wonder how to get the time down?

Golly, I don’t know. None of my plays have broken four hours. Not even three hours, I don’t think. (Maybe a little over three hours.) So I’m not sure what to tell you.

You must have some ferociously COIN-fluent players to rattle this game out in sub-4 hours. It’s hard to see how that’s even possible with CORP and CR needing quite a while to ramp up. Does that mean you had relatively early wins for MarsGov or Red Dusters?

We’ve had some early wins, but have also gone through all three storms.

But yes, we do have COIN veterans. Most of our players have gone through every volume.

thank you for a (as always) great review! is it now you favourite COIN (for solo only) ?

I actually haven’t played most of these in solo mode!

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Better Together? | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Book Shelf 25-1 ~ Quantifying Counterfactual Military History (Brennen Fagan, Ian Horwood, Niall MacKay, Christopher Price, and A. Jamie Wood, CRC Press, 2024) – Rocky Mountain Navy Gamer